This was not an idle requirement on the part of the authorities. What was the point of the Jewish Oath in the first place? The European Christian authorities did not trust Jews (or any dissenting religious minority) and believed they could and would lie in court. However there had to be means of taking testimony from Jews, so they devised various forms of an oath that, in their opinion, would be of such gravity that even the people they viewed as treacherous would have to feel bound by their own oath and tell the truth.

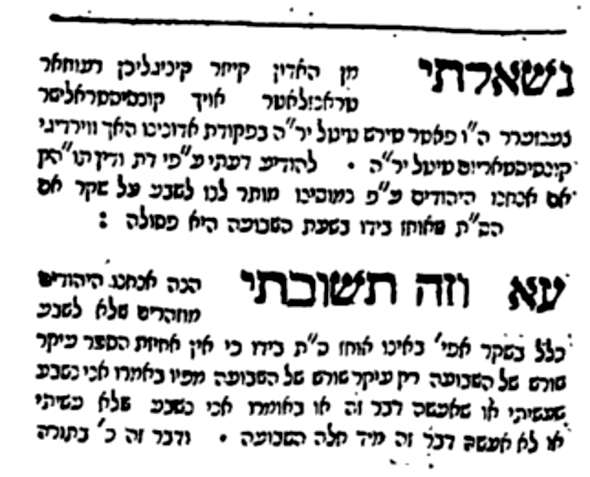

Evidently it was assumed that a kosher Torah must be used, but at least one government official had his doubts and so he asked a she'elah, a question of Jewish law, to Rabbi Ezekiel Landau. Was it true, Father Tirsch (the imperial translator and consistorial censor and other titles that I don't entirely know how to translate) wanted to know, that Jews were allowed by their religion to swear falsely if the Torah scroll they were holding was invalid? The latter included this question and answer in his responsa Noda Beyehuda (Volume I, Yoreh Deah 71):

The answer begins: "We Jews are careful not to ever swear falsely, even without holding a Torah scroll at all, because holding a Torah scroll is not the essence of an oath. Rather, the declaration by mouth is what makes an oath. As soon as a person says "I swear to do this or that, or not to do it" he is immediately bound by his oath.

He goes on to say that this can be proven from the Torah, the Talmud, from Maimonides and the Shulchan Aruch, and shows all the sources which demonstrate that an oath doesn't require holding anything at all. He goes on explain that the custom of holding or touching a book, or an object like tephillin, is only to make an impression of the gravity of the oath upon the person.

It's also interesting to reflect on the situation: this official is asking a rabbi if it's true that Jews can lie under oath if they're holding an invalid Torah. Evidently Peter Tirsch expected a sincere reply, which tells you a little something about the complicated situation of Jewish and non-Jewish relations at the time.

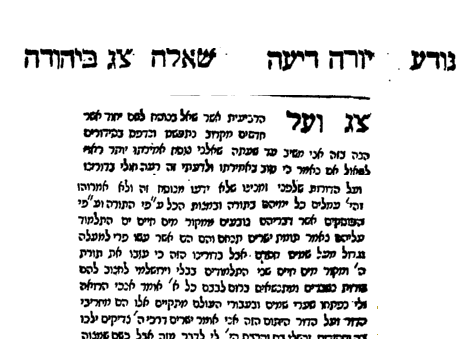

Incidentally, who was Father Tirsch? The Prague censor of Hebrew books in this period was Leopold Tirsch (1733-1788), who was the predecessor of Karl Fischer (I blogged about his relationship with the leading student of the Noda Beyehuda, Rabbi Elazar Fleckeles here). His name appears on the title page of this very volume of responsa:

The other post on the Jewish Oath mentioned that it required Jews to make a לשם יחוד recitation. There I questioned what the Noda Beyehuda would have thought about it. I meant in light of his well-known opposition:

In this responsum (YD 93), dated 1776, he was asked what the correct text of the leshem yihud ought to be. The questioner must have been startled by his reply, which was that he should have asked if it is proper to say it altogether! He then calls the recitation a sickness of the generation, whereas the pious ones of earlier generations did not say it. He concludes that the blessing is the preparation for the mitzvah, and for any mitzvah that has no blessing (sorry Fiddler on the Roof rabbi - there isn't a blessing for everything) you don't have to say anything, although he personally declares "I am about to perform this deed to fulfill the command of the Creator."