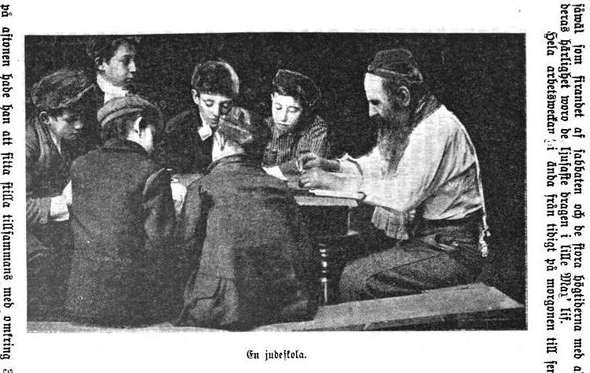

I give pride of placement first to some cheder yingelach. This one is from 1901. Some of these may be or certainly are posed, by the way:

Next is a photo I haven't seen of famous Jewish apostate and Masoretic scholar Christian David Ginsburg (1905):

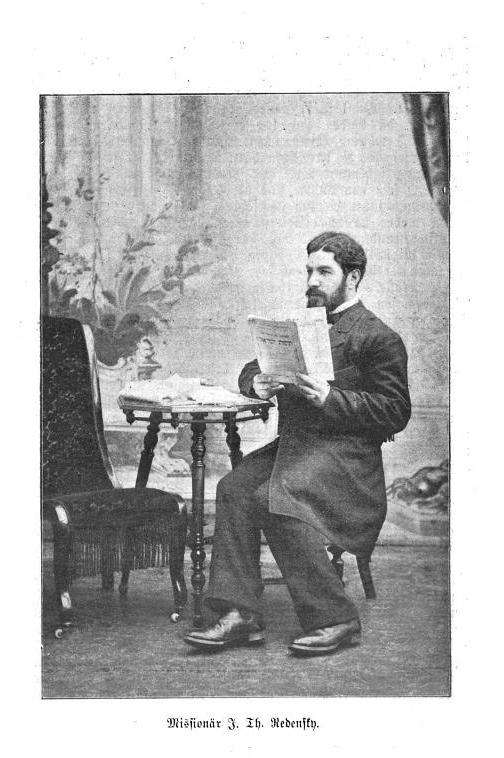

Here is a missionary named J.T. Redensky (evidently Johannes Theodor). This is interesting, because he is reading what looks like a Hebrew periodical of some kind. In fact, it's likely just the title. Unfortunately I can't read the first word, so I'll guess what it says - ישועת ישראל, even thought to my eyes it looks more like חרות ישראל .

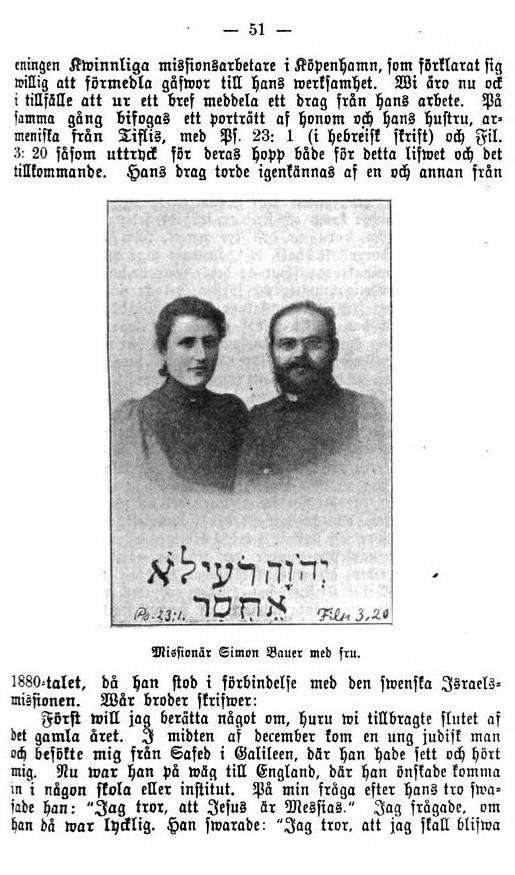

Next is a photo of a missionary couple, which I thought was interesting because of it's "The Lord is my shepherd" inscription in Hebrew:

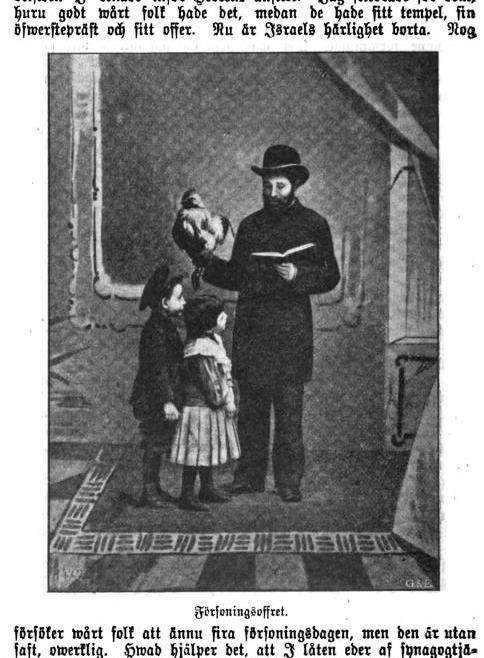

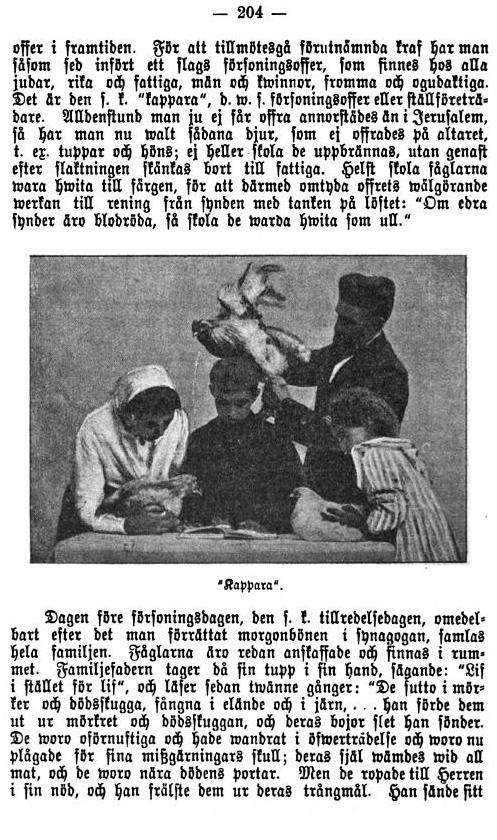

Here are two photos of kapparos being performed:

Two photos of Jews, including one captioned Talmudstuderande (from 1897):

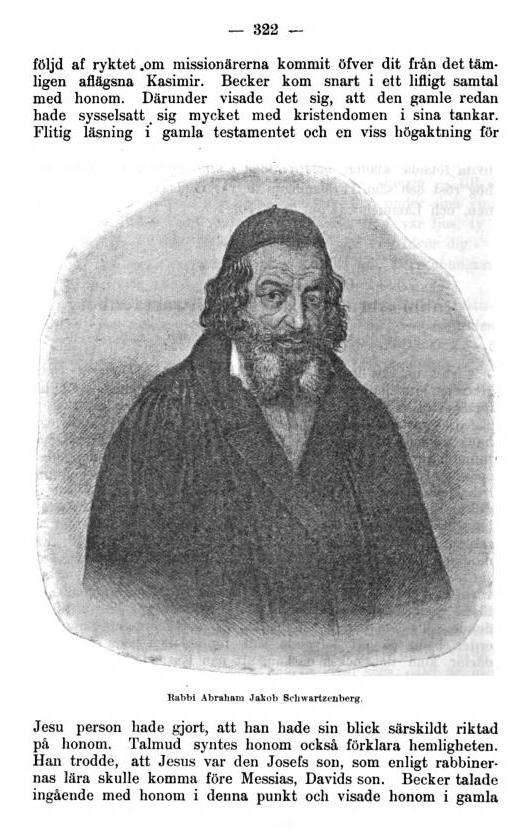

Finally, below is so-called Rabbi Abraham Jacob Schwartzenberg (1862-1843):

This Rabbi Abraham Jacob Schwartzenberg may well have gone down as Alexander M'Caul's most famous converted Jew if not for certain circumstances propelling Ezekiel Stanislaus Hoga to that position (and he wasn't actually converted or baptized by McCaul, see here). Evidently Schwartzenberg was an actual rabbi in Warsaw, and he converted to Christianity in 1828 after receiving a New Testament from a missionary named F.W. Becker. McCaul, who headed the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews baptized him.

He spent the next 20 years missionizing to fellow Jews - in full traditional dress, which he never ceased wearing. He is quoted as giving the following reason for retaining his dress and living among Jews: "The Jews often think that persons are baptized in order to escape reproach, or to live in Christian quarters of the city, or to walk in the "Saxon Garden" (from which then Polish Jews were excluded), but I will show them that none of these things move me. I am a Jew still - formerly I was an unbelieving Jew, but now I am a believing Jew, and, whatever inconvenience or reproach may result, I wish to bear it with my brethren." — who thought he was mad, of course.

In fact, such tropes appear quite often in the history of conversions. A Jew converts, other Jews say he or she did it for material gain and not conviction. In no few cases this could be proven. Still, in others it was undoubtedly out of conviction, and evidently Schwartzenberg desired to prove that was so in his own case. Elisheva Carlebach points out that the Jewish apostate Giulio Morosini (formerly known as Samuel Nahmias) describes his family's wealth and influence in his דרך אמונה Via della fede: mostrata à gli ebrei (1683), in order to silence Jewish critics that say he converted for financial gain (Pursuit of Heresy pg. 241).

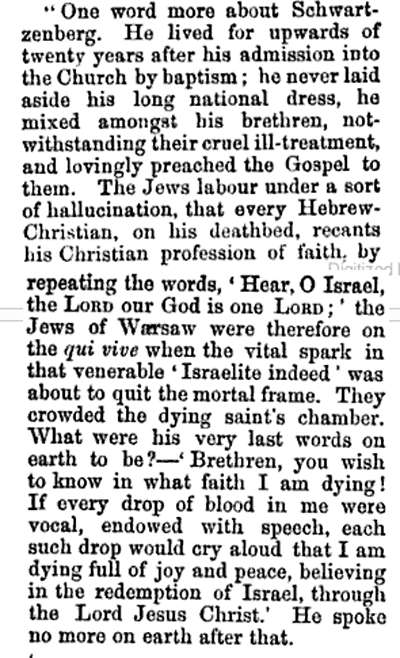

Here is how Schwartzenberg's death is described:

This is interesting, because it records the contention that Jews typically claimed that apostates repented, or at least recanted, before death. Although we have solid evidence that Stanislaw Hoga did indeed recant many years before he died, the legends about him have him repenting when he was close to death. For more on that see my posts, but even more importantly, read The Baal Teshuvah and the Emden-Eibeschuetz Controversy by Dr. Shnayer Leiman, or listen to his lecture The Meshumad, which is based on his essay. Also see Stanislaus Hoga—Apostate and Penitent by Beth-Zion Lask Abrahams JHSE 15.

Naturally there are other interesting pictures scattered through the volumes of the Missions-tidning för Israel and you can browse them yourselves here.