The image below comes from the first publication, in אוצר טוב, the Hebrew supplement to the Magazin fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums (1885 issue). This periodical was founded and edited by Abraham Berliner, and then edited by his colleague at the Hildesheimer Seminary, Rabbi Dovid Zvi Hoffman (so in case anyone ever wondered if there ever was a posek of stature with an interest in publishing such nahrishkeit, the answer is yes).

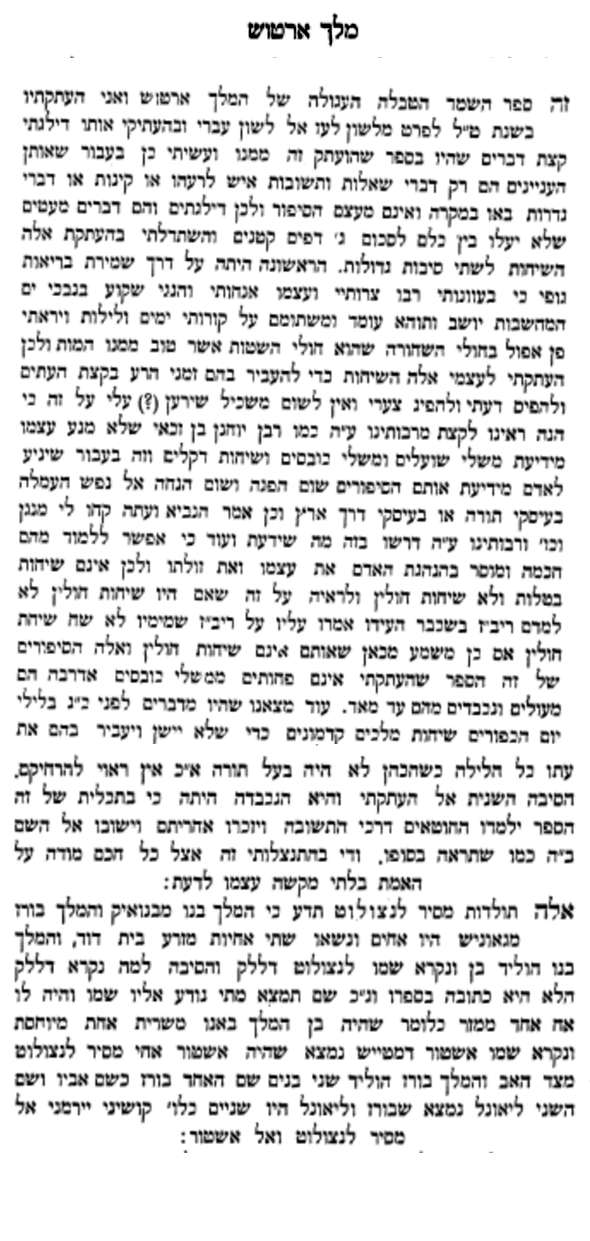

This work, called Melech Artus (King Arthur) in אוצר טוב was translated into English by Haham Moses Gaster with the name The History of the Destruction of the Round Table as Told in Hebrew in 1279 (Folklore 20.3 (1909), so there is no point in retranslating. Here is his translation of the passage above:

1. This is the book of the destruction of King Artus' Round Table. I translated it in the year (.. 39) (1279) from the vernacular (La'az) into Hebrew. In my translation I have left out some portions contained in the original book from which I translated. I did so because those passages were only dialogues and elegies or other accidents which happened to creep in without belonging to the body of the tale; I therefore passed them over. All together they would not be more than three small leaves. And I have undertaken this translation for two weighty reasons. First, I wished to preserve my bodily health. For through my sins have I met with troubles and sorrows and grief, and I am immersed in the sea of thoughts, marvelling and wondering constantly on the vicissitudes which have passed over me by days and nights; and I was afraid lest I fall a prey to melancholy, which is to lose my reason, than which death is better. Therefore have I translated those tales for my own pastime, and to drive away the thoughts which encompass me, and to soften my grief. Surely no one will take it amiss that I should have done so, for even our great sages, like R. Johannan ben Zakkai, cultivated also the study of the fox tales and the washer-women's tales and the parables of the trees; for through such occupation men derive some comfort and peace of mind, notably those engrossed in the study of the Law or in pursuits of the world. And the prophet himself asked for one to play on the harp to him, and our sages have explained it as you are aware. One can moreover derive from these tales some moral lessons in manners, and the conduct of man towards himself and towards others. They are therefore not mere idle talk and wasteful occupations, for the best proof lies in the fact that, if they were so, a man like R. Johannan would not have occupied himself with their pursuit, for of him it is stated that he never uttered an idle word all his life. You see there from that they did not consider those tales as mere idle talk. And similarly the stories which I have translated from this book are anything but idle talk, and they do not fall short of the washer-women's tales; on the contrary, they are far superior to them and more noble. We find also that on the eve of the Day of Atonement they used to tell tales of ancient kings to the High Priest all through the night, in the event that the High Priest happened not to be a scholar. It is therefore right not to eschew them. Another and more important reason for my translation has been, that the sinners might learn from it the way of repentance and think of their end and return to the Lord, as you will see at the end of the story. To the man who admits the truth and has an open mind, who is not obstinate or refuses to learn, I think I have stated sufficiently the reason for my action.Note: another translation was made by Curt Leviant in 1969, King Artus: a Hebrew Arthurian Romance of 1279. In addition, there is an article by Tamar S. Drukker called A Thirteenth-Century Arthurian Tale in Hebrew:A Unique Literary Exchange in Medieval Encounters 15 (2009) 114-129, which includes yet another English translation and analysis.

2. This is the history of Messer Lancolot. Know that King Bano of Benook and King Borz of Gaunes were brothers. They married two sisters, descendants of the House of David. King Bano begat a son, and he called him Lancolot del Lac (or dellek). The reason why he has been called del Lac is written in his book, where you can find it also (told) when he got to know his own name. He had a brother who was a bastard, namely the son of King Bano and of a lady of noble birth; the name of the bastard was Estor de Mareis (Mates); he was thus the brother of Messer Langclot on his father's side.

3. King Borz begat also two sons, one called Borz after his father, and the second Lionel. Borz and Lionel were therefore, as we would call them, " cosini iermani " of Messer Langolot and Estor.

As you can see, the author knows that not everyone approves of such literary activity, and defends it on two grounds. First, he is not well and such an activity is therapeutic for him. And really such a translation is not a bad thing in its own right.

After all, Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai did not have disdain for fox fables (משלי שועלים) and the like (Sanhedrin 38b). In addition, there is biblical precedent for bardic diversions. The reason these things are alright is because there are lessons and morals to be learned from them, and the proof is that Rabbi Yochanan would have distanced himself from them otherwise. In addition, to keep the Kohen Gadol awake on Yom Kippur night, if was not learned they'd read to him שיחות מלכים קדמונים (Mishnah Yoma 1.6; here our author is playing a little loose. What he calls "tales of ancient kings" the Mishnah calls the book of Job, Ezra and Chronicles (and according to one eyewitness, Daniel). Strictly speaking it's true, kind of. But איוב ובעזרא ובדברי הימים is not exactly the same as שיחות מלכים קדמונים.

Finally, the second and more important reasons, is that the story itself instructs by example that sinners should repent.

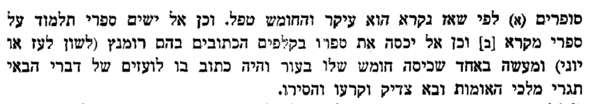

Obviously the author was well aware that there were critics of works like his. Not everyone thought there was any value in medieval romances. The frequently critical attitude of rabbis toward Immanuel of Rome (1261-1328, and therefore a contemporary of the author of the Arthur translation) is well known (e.g., the Shulchan Aruch OC 307:16 singles out one of Immanuel's works as forbidden to read on Shabbat - or any time: מליצות ומשלים של שיחת חולין ודברי חשק, כגון ספר עמנואל, וכן ספרי מלחמות, אסור לקרות בהם בשבת; ואף בחול אסור משום מושב לצים ). Sefer Chasisim 141 (0r 142 in some editions) doesn't single out Immanuel, but suggests that one should not even bind books with pages from romances (רומנץ) in Greek or Latin:

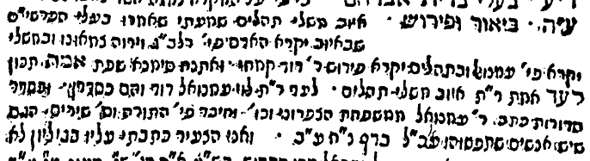

Here seems like an appropriate place to call attention to something which should be better known. Despite the negative rabbinic attitude toward עמנואל, the Chida writes concerning which are the best commentaries on certain books of the Bible. For Mishle, Proverbs, it's Immanuel's commentary.

A nice example of putting "accept the the truth" into practice. Immanuel even gets to be the ע in אמת לעד, the mnemonic device for remembering which authors and which commentaries.