Leviticus 13:46 in Parashas Tazria states that the mezorah (leper) "shall dwell in isolation; he shall be outside the camp." Chazal taught that his affliction is caused by his speaking leshon hara, gossiping about others (Arachin 15b). Rabbi Sorotzkin beautifully comments on the point that this individual receives tzara'as because of his antisocial behavior. He spreads rumors about people because he hates individuals. But this is only initially. His pattern of behavior eventually causes him to hate people generally and to only wish ill for them. So it is only right that he suffers a plague himself. However, through this plague is the very cure with which he can learn to correct his ways. He must face total social isolation by being alone outside the camp. This will cause him to crave human company. Parenthetically, adds Rabbi Sorotzkin, the pain of solitude is brought out most vividly in the book Robinson Crusoe. By being isolated from the community, the mezorah will learn to appreciate the very people he said nasty things about and wish to rejoin them.

Rav Sorotzkin:

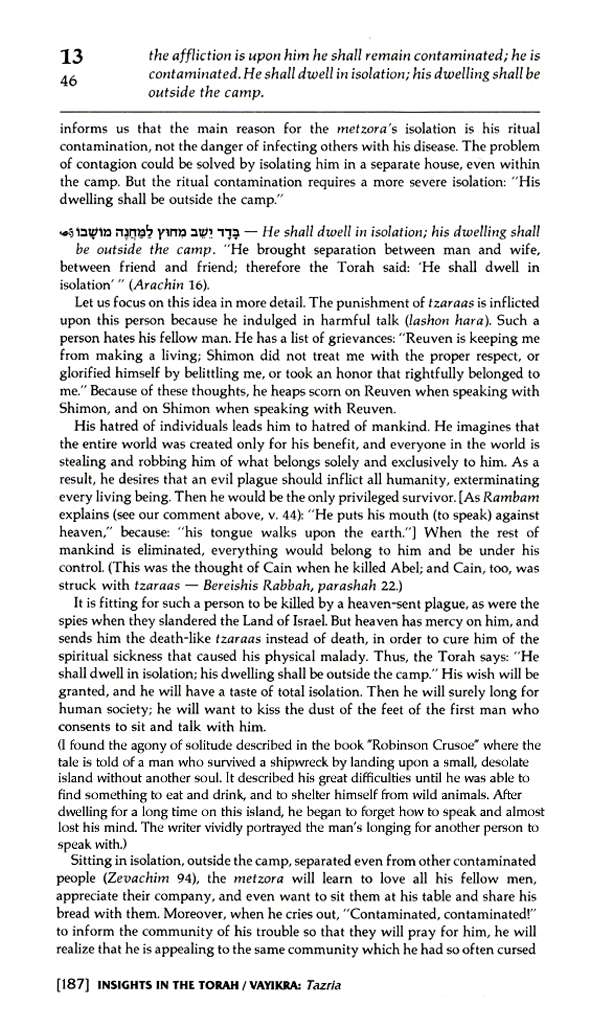

So here is the Artscroll translation :

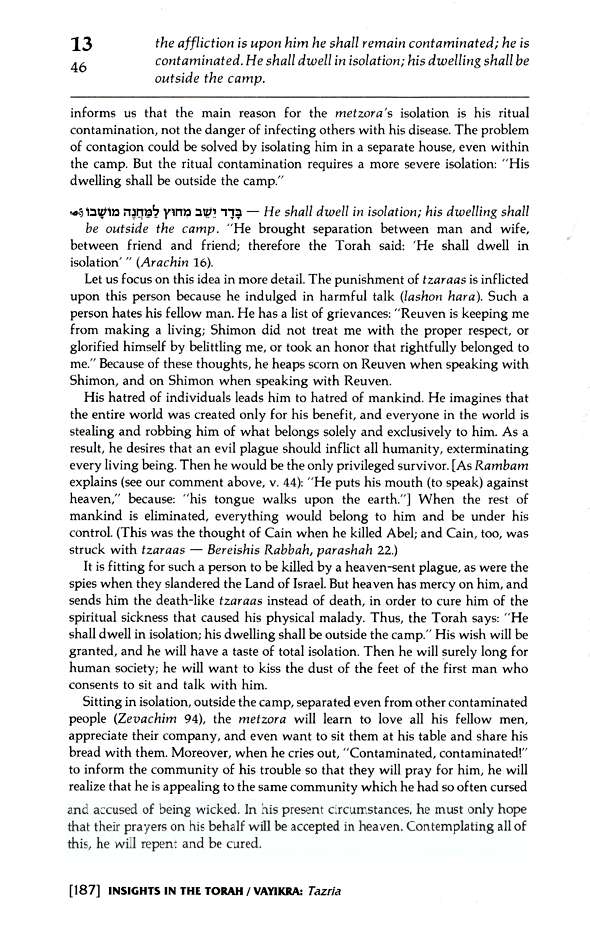

Except actually that's not what the page looks like. The remark about Robinson Crusoe—"I found the agony of solitude described in the book "Robinson Crusoe" where the tale is told of a man who survived a shipwreck by landing upon a small, desolate island without another soul. It described his great difficulties until he was able to find something to eat and drink, and to shelter himself from wild animals. After dwelling for a long time on this island, he began to forget how to speak and almost lost his mind. The writer vividly portrayed the man's longing for another person to speak with."—was added by me. For some reason in the Artscroll "complete classic commentary" that entire paragraph about Robinson Crusoe is missing. Here is what it looks like:

And here is the original commentary in אזנים לתורה:

This is kind of odd. Why would a little paragraph about Robinson Crusoe be removed?

Various guesses, all based on the theme that the inclusion of a reference to Robinson Crusoe is discordant with yeshivish hashkafah:

- It doesn't seem natural or proper that an authentic Lithuanian rosh yeshiva of the previous generation, the pride of the great Telzer yeshiva, would have even read Robinson Crusoe much less included a reference to it in his Torah commentary.

- Even if it was not written by himself, but based on oral talks, it doesn't seem right that he should have referenced Robinson Crusoe in an oral talk on the Torah.

- While not explicitly doing so, he almost seems to recommend reading it.

- It appears strangely close to the much-maligned Torah U-Madda approach.

- This is farfetched, but it is interesting that one of Orthodoxy's favorite arch-heretics, the hebraist Eliezer Ben Yehuda, many times cited his having read כור עוני, Yitzhak Romesh's Hebrew translation of Robinson Crusoe, which was secretly shown to Ben Yehuda by his half-maskil rebbe, R. Joseph Blucker (?). See, for example, his autobiographical החלום ושברו. Reading the fine prose of this book helped kindle a love for the Hebrew language within him.

Come to think of it, I wonder if Rabbi Sorotzkin realized that it was fiction? It isn't clear to me from his words that he did, since otherwise what he was saying is that an author of fiction portrayed very clearly a certain type of experience which neither he nor Rabbi Sorotzkin had. Would he really cite the work of someone's imagination as a way in which to understand the Torah? (Yes.)

This is not as strange as it seems. The book is written in first person, and the original title was "The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner: Who lived eight and twenty Years all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself." Furthermore, the title page promises that it was:

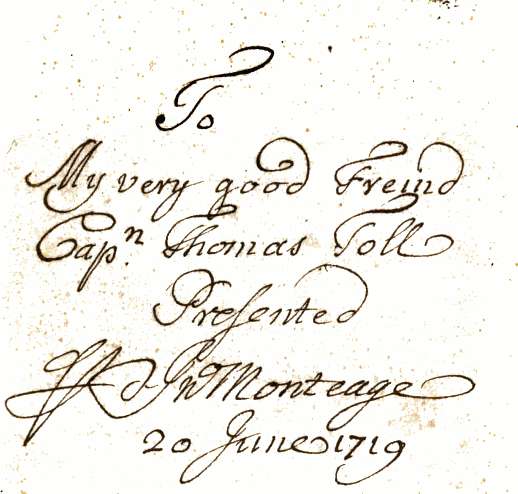

Incidentally, one of the cool things about Google Books is seeing something like this in one of their many 18th century copies of Robinson Crusoe:

It should also be noted that in novels were in very ill repute in the 19th century (and the 18th). They were disliked by pious people of all faiths, and also by many non-pious but serious people. Novels were widely regarded as imagination gone amok, liable to arouse impious and impractical thoughts; a waste of time. Furthermore, very often novels were written as if they were real, using various literary devices to give that impression.

In the Chasam Sofer's ethical will written to his family in 1839 he commands that והבנות יעסקו בספרי אשכנז בגופם שלנו המיוסדים על אגדת חכמ"זל ולא זולת כלל—the girls [in his family] should only read Yiddish books written in Judeo-German type, based on the aggados of Chazal, and nothing else. By the way, the presence of this passage lends a modicum of plausibility (but not enough) to the possibility that his will really did read ובספרי חמד אל תשלחו יד (don't reach your hands for romantic novels) and not ובספרי רמד אל תשלחו יד (don't reach your hands for Mendelssohn's books)—more on this in a future post.

In similar fashion, in Samuel David Luzzatto's autobiography he writes about how he read a French novel called Alexis as a child. In the novel, Alexis is a boy born into nobility who is somehow snatched from his family and ends up living with peasants. One day a gentleman spots him and sees that this peasant boy is holding a copy of Virgil in his hands! Realizing that he is a noble boy, he takes him and restores him to his station. Around this time Shadal had childish cause to be upset at his parents, so having read this book he decided to run away. He did so, skipping school, and taking a philosophy book by Condillac with him. After a few hours of wandering, a kind man decided to question the child wandering around in middle of the day and brought him home to his parents (who didn't realize what happened, since it was lunchtime and he was due home then anyway). He writes that this was the end of his reading novels, and lucky him, because who knows what would have become of him otherwise?

But I digress. Every Hebrew edition of Oznayim Le-Torah has the paragraph about how Robinson Crusoe portrays the agony of solitude. But whatever the reason, the paragraph is missing in the Artscroll translation.