The first is from a letter by Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), who was a controversial 18th century British Unitarian theologian who discovered oxygen and soda pop, among many other notable things in a very notable life. Priestley, by the way, moved to the United States after his home was attacked and burned to the ground by a mob on the first anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille (see the Priestley Riots, in which supporters of the American and French Revolutions were attacked).

Priestley happened to have felt that Jews might find his Unitarian beliefs amenable and convert if Unitarian Christianity were presented to them in a friendly way. So it was that he addressed an open letter to the Jews, with which he claimed he wanted to open a discussion with Jews. Apparently he didn't really expect a conversation, but he got one anyway in the form of British Jewish haberdasher David Levi, and a whole series of open pamphlets were exchanged. In any case, his collected letters were published in 1832, and below is an interesting excerpt from one dated January 23, 1788 to a fellow Unitarian minister, Newcome Cappe:

As you can see, he writes that his letters to the Jews don't seem to be producing converts. However, claims he, a "learned Jew of Konigsberg" is translating his letters into Hebrew. Evidently he planned to print them in England, but nothing ever materialized. However, most interesting is that the unnamed learned Jew sent him three volumes of "a periodical work, designed to promote literature among the Jews. It is in Hebrew, with a small part of it in High Dutch." Priestley is talking about none other than Ha-Meassef, the first periodical of the German Haskalah published in Koenigsberg. Apparently it was of no interest to Priestley, so he says, though I have a hunch he couldn't understand it.

"High Dutch," by the way, is a literal English translation (with modified English pronunciation) of hochdeutsch. Since he differentiates from "German" I think he means Yiddish, or more accurately the highly Germanized Judeo-Deutsch spoken by Jews of Germany. In fact, in English literature of the period the Yiddish spoken by Jews is often called "High Dutch," which leads me to the next interesting excerpt.

The following is an excerpt from a 1682 English translation of a critical work on the Bible by Richard Simon. The background concerns the Samaritan Pentateuch. In 1616 the Italian traveler Pietro della Valle brought a copy of the Samaritan Pentateuch which he had acquired in Damascus back to Europe. While it had long been known that the Septuagint must have been translated from a different Hebrew text from the one which was extant, the present existence of a different Hebrew text had never even been suspected (I think?) and it caused a sensation. Not only was the text variant with the seemingly uniform Hebrew textus receptus but it was even written in the archaic paleo-Hebrew alphabet which, was felt, had been used by the Jews prior to the time of Ezra. Thus, suspected (and hoped) many scholars there were good grounds for considering this newly discovered text to be even older than the masoretic text. This was especially felicitous, as Samaritan Hebrew has no vowels which meant that there is indeed an authoritative Pentateuch without pesky points telling you how to read it. Furthermore, in many cases the Samaritan reading agreed with the Septuagint or at least seemed to differ from Jewish exegetical positions implied by the masoretic Hebrew text.

Since the net result was the undermining of the Hebrew textus receptus, naturally proponents of that text sought to discredit the Samaritan. Richard Simon, a French scholar who is credited by some with being one of the earliest to cast doubt on the Mosaic authorship of the Torah, was yet of the opinion that the Samaritan text was inferior to the masoretic. Here he is arguing that the mere fact that the Samaritan text is in ancient Hebrew alphabet is no proof that they preserved the text most accurately, for these same Samaritans write their native Arabic with the very same ancient alphabet, as do several other peoples write their vernacular language in an alphabet which is not their own. Thus, this does not prove that they kept an ancient, perfect copy of Moses's Torah in the correct original script. Rather, it is equally plausible that they kept a corrupt copy, the characters they use proving nothing.

Simon notes as well that the Jews of his own time "often write the high Dutch in Hebrew characters."

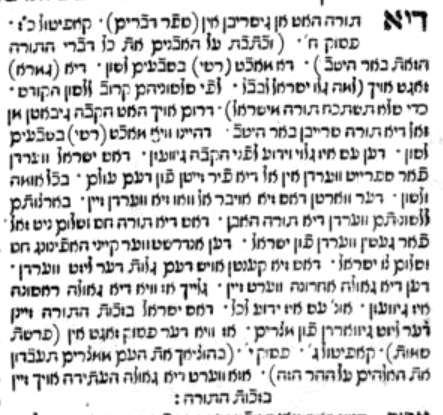

Here's an example of "high Dutch in Hebrew characters" from roughly the same period.