In Cyrus Adler - Selected Letters (ed. by Ira Robinson) we find the following excerpt from a letter from the 20-year old Adler, then an Oriental and Semitics student at Johns Hopkins, dated November 7, 1883 to his rebbe Sabato Morais. He writes:

"Could you give me any references or information concerning the word מרחשון? I think it can be identified with the Assyrian Arax samna which you will recognize as meaning "the eight month."(Ira Robinson strangely footnotes that Marheshvan is a variant (!!) of the name for the second month of the Jewish year, evidently forgetting that counting from Nisan (הַחֹדֶשׁ הַזֶּה לָכֶם רֹאשׁ חֳדָשִׁים) Marcheshvan is indeed the eight month.)

My guess is that the youthful Adler did not realize that as a Semitics student in all likelihood he already knew more about it than his mentor. If this was fairly cutting edge scholarship in 1883 - it was very old news by 2000! Zivotofsky is hardly to be faulted for pointing out 130-year old news to his audience, which certainly included me, which mostly had never heard or even imagined it. In fact, he is to be congratulated for writing that article.

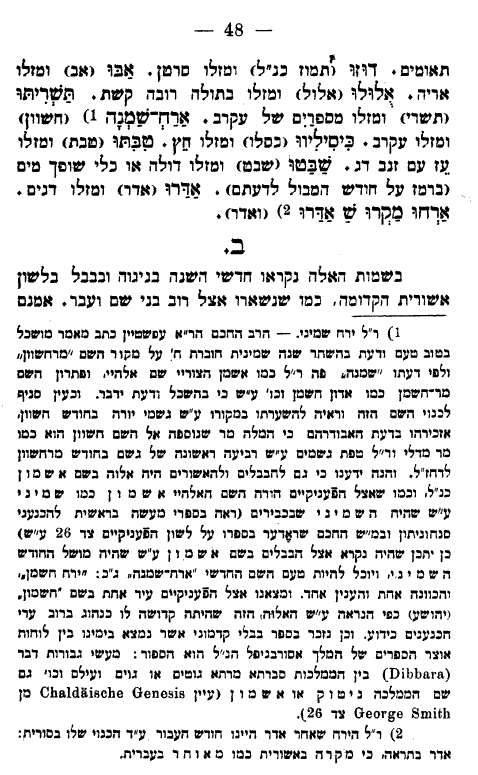

In 1n 1882 book called בירוסי הכשדי, או, קדמוניות האשורים והבבלים this is discussed by Solomon Rubin (pp. 48-49, 106, and 153):

On second thought, although Adler probably already knew more about Semitics than his mentor, I suppose Morais may have already had this book - he was very learned and well read in the latest scholarship.

Similarly, in Abraham Epstein's 1887 book מקדמוניות היהודים there is a great, much more complete discussion, מרחשון ·ארח-שמנא, (beginning on pg. 23):

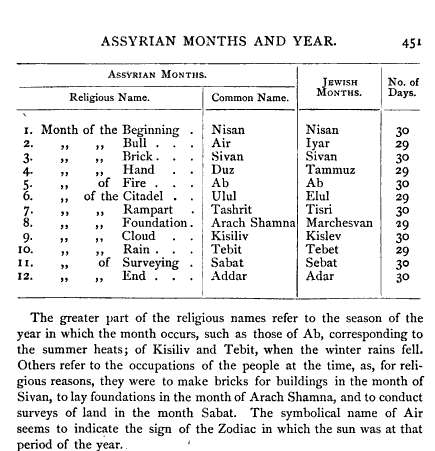

Of course this was not the discovery of maskilim writing in Hebrew, but was rather the recent findings in Semitic scholarship, bolstered by the decipherment of cuneiform. For example, see this table from an 1869 book by François Lenormant,Manuel d'histoire ancienne de l'Orient jusqu'aux guerres médiques: Assyriens, Babyloniens, Mèdes, Perses. This was not his discovery; I don't think it was news even in 1869. Here is the table in English translation (1871):

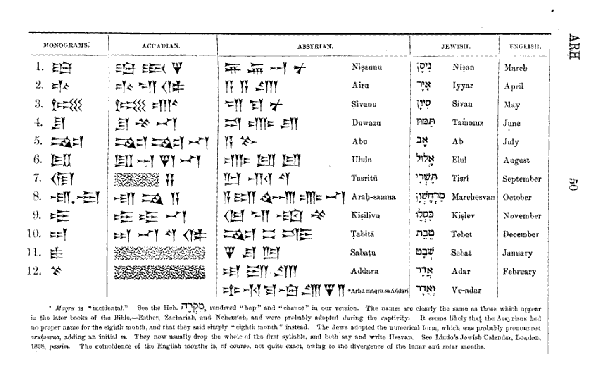

One of the sources Epstein cites is Edmund Norris's Assyrian dictionary (1869), which shows the following:

Finally here is some excerpts from an article by Dr. B. Barry Levy which dealt incidentally with the way in which this etymological issue is dealt in two separate books published by Mesorah Publications - Artscroll. I trust the reader will find this interesting, if not debatable:

Rabbi David Feinstein’s The Jewish Calendarcont.

One of the most recent books . . . is Rabbi David Feinstein’s The Jewish Calendar: Its Structure and Laws (2004). It begins with a long list of donors and seems to have some association with the rabbi’s yeshiva. It was issued in a special edition before the formal release, perhaps as part of a fund-raising effort. In any case, the book thanks, among others, Rabbi Nosson Sherman for his extensive assistance, but unlike most other Artscroll volumes, Rabbi Scherman seemingly has not provided its Overview. One does find an Overview (pp. 13-24), but it is not signed, so one must assume that Rabbi Feinstein is its author. Yet, when one compares these pages with the rest of the book, one immediately senses a difference. Much of the book explains how the calendar and related liturgical practices function. It begins with the generic Rosh Hodesh and works through the months in sequence from Tishrei through Elul. The volume is packed with details some people may not know, but much of it is fairly elementary. The Overview is a mix of this type of material and the kind of treatment one finds in many of Rabbi Scherman’s Overviews in other volumes. His mark is there, even if his name is not.

I cannot tell which of these two gentleman (or perhaps one of the other contributors) produced pages 71-74, which are devoted to the month following Tishrei, listed there as “Cheshvan.” The chapter begins by noting that, “The word mar is commonly added to the word Cheshvan, so that the month is called Mar-cheshvan. In the plain sense, this is because the word mar means water, as in ke-mar mi-deli, like a drop of water from a bucket. Because Cheshvan is the beginning of the rainy season in Eretz Yisrael, it was natural to add the word for water to the name of the month.” Isaiah 40:15 is footnoted, as are Even Ha-Ezer 126:7 and Peri Hadash, a.l. This is followed by various explanations of mar as “bitter” and why water, which is needed in this month, might be considered bitter.

The text continues, “Another reason for attaching the prefix mar to Cheshvan is because mar generally means bitter, and this month not only lacks festivals, it also recalls one of the bitterest events in Jewish history.” The explanation refers to the rebellion of Jeroboam, set in this month, which included setting up a competing sanctuary and a celebration at the full moon.

The first of these explanations is designated by the writer as “the plain sense,” which I take to mean the simple, straightforward explanation, the peshat. I beg to differ; both explanations are incorrect. According to the Palestinian Talmud, Rosh Ha-Shanah 1:2, shemot ha-hodashim `alu be-yadam mi-bavel, “the names of the months ascended with them [the returnees at the time of Ezra and Nehemiah] from Babylonia” (as did several other things). This refers to the fact that, in pre-exilic books, the biblical months are usually identified by numbers, while in post-exilic books they appear in the forms familiar from our current calendar: Nisan, Elul, Tishrei, Adar, etc. The point of this talmudic statement is that the returning Israelites brought with them the names of the Babylonian months, and indeed, in Akkadian, the language of Babylonia at that time, the months are called Nisanu, Elulu, Teshritu, Adaru, etc. Except for the –u ending, they are all virtually identical to the Jewish months.

In this Akkadian calendrical system, the month after Teshritu is called M/Warahshamna, m and w being a commonly found phonetic interchange (cf. “purple,” which is ’argaman in Hebrew but ’argevana in Aramaic; also Akkadian Kislimu and Simanu correspond to Kislev and Sivan). Like the numerical designations and the few agriculturally based month names found in early biblical books and unlike most of the later Hebrew month names now in use, in Akkadian the name of this month actually means something; it is a composite of two words, warah or marah, cognate of the Hebrew yerah, “month,” and shamna is cognate of the Hebrew shemini, “eighth.” Following the lead of the Yerushalmi, we can conclude that Marheshvan is actually Akkadian in origin and that it means “the eighth month.” This makes perfect sense, because, in their respective calendars, Tishrei and Teshritu are the seventh months. (Cf. October, which falls at the same time of the year and also means “eighth month” but became the tenth month of the calendar when July and August were added in the middle of the year.)

All of this demonstrates conclusively that mar in the month name is neither the Hebrew word “bitter” nor a word mar meaning “water” (though this is the accepted meaning of the word in the verse cited from Isaiah). Indeed, in this context, mar is not a word at all. Rather it is part of marh-, which means “month”; it is not a prefix but an essential part of the first word of a compound name. It was not added to Cheshvan by some people for a homiletical reason but omitted by some from Marcheshvan, probably for a superstitious reason (to avoid associating the month with bitterness) or perhaps because many of the other month names contain only two syllables. Marheshvan is the correct Hebrew name (actually used on page 118). Over the centuries, the above philological information was lost, and therefore, to some extent, the proper understanding of the passage in the Yerushalmi was lost too.

This is far from the first time the above explanation has been put forward; indeed it is a commonplace for anyone who deals with ancient Hebrew, Aramaic, and Akkadian, and with the biblical or talmudic calendars, not to mention talmudic archaeology. But a form of learning that shuns all forms of external information not sanctioned by an approved rabbinic writer has its liabilities, and in this case it has allowed clever guesswork and homiletics to replace the simple truth.

The principle of relying on foreign languages for comparative philological purposes was well established among the geonim and subsequent medieval writers but less essential to some later rabbis, who were either less knowledgeable of them or mystically inclined to ignore them. But this principle, though disputed in limited contexts, was challenged only in the context of the Torah and then only by some people. As can be seen from the considerations of many other early writers, this is not an issue with words in later books of the Bible, surely not in rabbinic literature, and Marheshvan does not appear anywhere in the Bible. As far as I am concerned, there is simply no reason not to present the authentic explanation of the name Marheshvan and to sustain the effort in the analogous pursuit of the correct meanings of other biblical and talmudic words, but note the following:

Shemot hadoshaim `alu imanu mi-bavel (PT RH 1:2), Month names ascended with us from Babylonia”: Because initially, according to our original usage, they did not have names. And the reason for this is that initially their numbering system was a memorial to the Egyptian exodus. But when we ascended from Babylonia and the Scripture was fulfilled: “No longer will it be said, ‘By the life of God who caused the Israelites to ascend from the land of Egypt’ but rather ‘By the life of God who caused the Israelites to ascend and brought them from a northern land,’” we returned to calling the months as they were called in the land of Babylonia, to recall that we were there and from there God, Blessed Be He, caused us to ascend, because these names – Nisan, Iyyar, etc. – are Persian.

This passage is taken from Nahmanides’s commentary to Exodus 12:2. Clearly there is nothing heterodox, much less heretical, about my interpretation; indeed, it is based on the Yerushalmi and was suggested in all but its linguistic details by Nahmanides in the thirteenth century. Did the author of these pages perhaps not know this text about the months, or did he prefer the comments found in a later commentary on the Shulhah Arukh to that in Nahmanides’s Torah commentary? If so, why? Why did the editor(s) not offer the alternative? We will return to this issue later. . .

The book on the calendar that carries Rabbi David Feinstein’s name derives Marheshvan from the Hebrew word mar, meaning either “bitter” or “water.” Yet, another Artscroll book by Rabbi David Cohen (Avraham Yagel Yitzhaq Yeranen (2000) pp. 23-24. Almost as important as his statement is his source, Abraham Epstein’s Qadmonyiot Ha-Yehudim, 1957.) not only says what I reported above about the Akkadian etymology of the twelve month names, it actually lists in Hebrew characters the names of all of the Akkadian months and tries to fathom why Marheshvan differs from its Hebrew equivalent more than the others; clearly the Akkadian base of the twelve names is a foregone conclusion for him. But Rabbi Cohen’s Hebrew books do not attract anything like the amount of media hype and market attention given to those of Rabbi Feinstein. Significantly, Rabbi Scherman’s Torah commentary weighs in on the issue as well, and here too one finds the preferred explanation, where he refers specifically to Nahmanides’ position in his commentary to Ex. 12:1: “The currently used names of the months are of Babylonian origin, and came into use among Jews only after the destruction of the First Temple. Those names were retained as a reminder of the redemption from Babylon, which resulted in the building of the Second Temple. (Ramban)”In short, why should we have to wait more than a century to learn old news? Too bad. But it's never too late.

Nothing about this thesis requires its avoidance, and Rabbi Scherman obviously was aware of it when he wrote the Torah commentary in 1993, long before this book on the calendar appeared. Dare I suggest that Rabbi Feinstein and the Rabbi Scherman who contributed to the volume on the calendar (minimally as General Editor, but he is thanked for much more) and the other rabbis involved with its production should have read and taken seriously Rabbi Scherman’s Torah commentary or Rabbi Cohen’s essay? Did Rabbi Scherman, editor, forget what Rabbi Scherman, commentator, had written?

There are several ways to explain this inconsistency, but I believe it results from a desire to leave this passage as it was out of respect for his colleague(s) and the belief that the position accepted by Nahmanides and Rabbi Cohen and adopted in his own Torah commentary, as well as Rabbi Feinstein’s, based on the Peri Hadash, are both “Torah” i.e., authoritative rabbinic teachings. Such an assumption gets Rabbi Scherman, editor, off the hook, but only momentarily, because, though this gesture might demonstrate great humility and respect for earlier rabbinic teachings and the contemporary use of them by Rabbi Feinstein, it also highlights a remarkable inability to differentiate between the truth and no longer useful attempts to get at it, perhaps even a lack of desire to pursue it. Though he got it right as author of his own commentary, he got it very wrong as editor.