First of all, just to show how deeply embedded the notion that the Maharal created a golem is, here is a note from a recently produced Torah sheet:

The Chacham Tzvi's teshuva of course does not mention the Maharal (nor was he the Maharal's grandson). It will be reproduced below. (Edit: in view of a comment which contended that I am mistaken in my point, I would like to clarify what I mean here: my point is not that the author positively asserts that the Maharal made a golem. Indeed, he writes "tale?" in a paranthetical remark. But the author is mistaken that Chacham Tzvi is the Maharal's grandson. Why should this mistake occur? See below for the teshuva which discusses his actual "grandfather." But it seems to me that when someone has it in their mind that so-and-so's grandfather is said to have created a golem, unless they're careful and unless they check, none other than the Maharal pops into mind.)

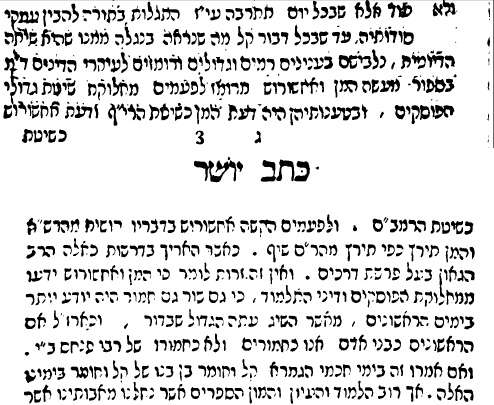

Concerning Saul Berlin's Ketav Yosher, the satire which he wrote in defense of Herz Wessely's Divre Shalom ve-Emet pamphlet concerning Jewish education, Leiman copied and translated the relevant passage, but here it is in the original (last paragraph):

For some reason the Maharal's name is given as מוהר"ר לוי instead of לוואי or some similar spelling, and maybe this is why the passage had been overlooked. Before I put in my $.02 about this, every now and then one comes across something that seems to be symbolic of a great gap in thinking between different Jewish camps. Here is what Rabbi Ya'akov Kanievsky, the Steipler Gaon, had to say when asked about the propriety of publicly discussing the matter of the Besamim Rosh, the infamous forgery apparently created by the aforementioned Saul Berlin:

"In my humble opinion it is not at all proper to publicize the disgrace of the author of "Besamim Rosh" for several reasons:Here we have the דעת תורה which basically forbids the Seforim Blog, my blog, and many others. By the way, I happen to agree with some of these points.

"1) Due to the honor of his ancestors (Berlin's family was one of the most elite rabbinic families in all of Europe; his father, brothers, grandfathers, uncles - we're talking the heavyweights).

"2) Perhaps his soul has already achieved it's rectification in Gehinnom, being that more than 150 years had passed. Recalling his sin will cause his soul harm.

"3) This episode brings disdain on many great rabbis who supported the forgery, but were mistaken.

"4) Many men might weaken in their faith due to the confusion caused by their awareness that one who was great in Torah (i.e., Berlin) was able to stumble into heresy, God help us.

"However, it is permissible to compile an essay regarding the accursed Haskalah (here he makes a common pun which can only be seen in Hebrew, Haskalah - enlightenment - with a sin and Haskalah with a samech are homonyms of opposite meaning) which destroyed German Jewry, which departed from its heritage, and also spread to other lands, however the names of those Torah scholars who were caught up in it should be omitted."

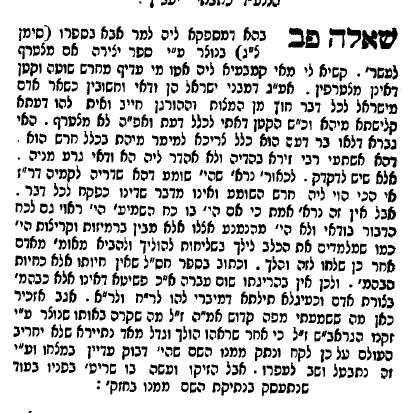

Here's a classic excerpt from the כתב יושר:

"The actions of Haman and Ahasuerus allude to various disagreements and positions of the great posekim. Haman acted as he did because he held like the Rif, but Achashverosh held like the Rambam. Achashverosh asked like the Maharsha, and Haman answered according to the Maharam Schiff. Don't protest that this is anachronistic, Haman and Achashverosh couldn't know the disagreements of the posekim and the laws of the Talmud, because even an ox and a donkey knew more in earlier times, as we see from the greats of the present generation. Like the Rabbis said, if the earlier ones were like people, we are like donkeys, but not even the donkey of Rabbi Pinchas ben Yair. If this was said by the sages of the Gemara, certainly it applies even more so in these days."

When I happened across this mention in the כתב יושר of a miracle of the Maharal juxtaposed next to another rabbi creating a golem, I was excited. The Maharal's golem is now so embedded in the public consciousness, as we see above, that people simply cannot think of a golem without thinking of the Maharal, and perhaps they can't even think of the Maharal without thinking of the golem. Yet in 1784 (when Ketav Yosher was written) or in 1794-5 (when it was probably posthumously published) the association was obviously not embedded in the mind. I initially wrote Dr. Leiman because I figured he knew which Maharal legend it referred to. Since it's funny, I'll admit publicly that I understood הוריד בירה מן השמים to mean that the Maharal caused beer to descend from heaven for the Emperor Rudolf to drink. I couldn't imagine that בירה here meant castle; the Maharal caused a castle to descend from heaven? What on earth could that mean? Dr. Leiman knew the legend and that it indeed referred to the Prague Castle.

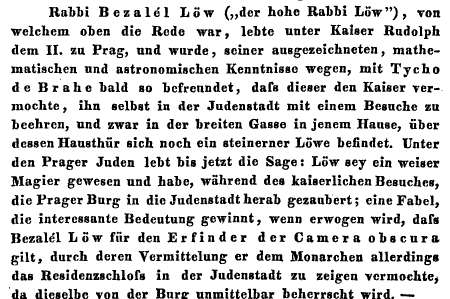

This legend is most interesting. In 1831-32 Julius Max Schottky published a 2-volume book called Prag, wie es war und wie es ist. On pg. 361 we find the following:

"Rabbi Bezalel Löw ("the tall Rabbi Löw") of whom we've spoken above, lived under the rule of Emperor Rudolph II at Prague, and with his excellent mathematical and astronomical knowledge became such friends with Tycho Brahe that the Emperor could honor the Jewish Quarter with a visit, in the house at the square with a stone lion in front that is still there. Among Prague's Jews there is still the following legend: They say that Löw was a wise magician, and that during the imperial visit he brought the Prague Castle into the Jewish Quarter, by magic. The legend is interesting because Bezalel Low was the inventor of the camera obscura, which was the means through which he could have shown the Monarch the Castle in the Jewish Quarter, which is right outside the Castle. "

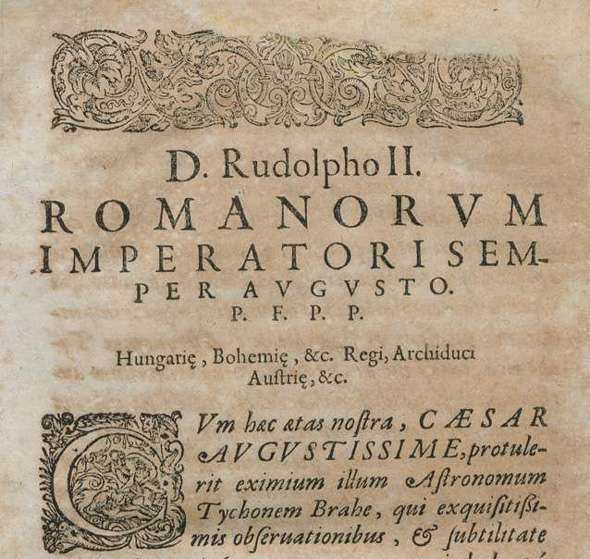

Putting aside exactness of the translation, here we see a non-Jewish historian, relating a legend which he says the Prague Jews still told in the early 1830s. The Emperor Rudolph II had such respect for the Maharal that he visited him. As a magician, the Maharal actually conjured the Castle for him right there in the Jewish Quarter (to show his hospitality? I would have thought a beer sufficed, but I guess that's not a miracle for a royal guest). Schottky adds that the Maharal invented the camera obscura, an interesting assertion to say the least, and in his view perhaps the germ of the legend is that he was able to produce an image of the Prague Castle for the Emperor using a camera obscura. An interesting fact from the Wikipedia page: "The term "camera obscura" was first used by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1604." This refers to his book Astronomiae Pars Optica. Look at the to whom Kepler dedicates this work:

In any case, clearly this is the legend which Saul Berlin is referring to, and it seems that the legend of the Maharal being הוריד בירה מן השמים which Schottky reports in the 1830s was in circulation toward the end of the 18th century.

Before I get to other golemic matters, it is interesting to pause and note that not only have no written sources prior to 1836 been found linking the Mahral to the golem, but that once they do appear they are all in German, not in Hebrew. Why is that?

In the first part of the 19th century in Europe there was a Romantic interest in collecting and publishing the oral folklore of the people, for the existence of the rich popular imagination of the masses was thought to be a potent sign of nationhood, and for the first time collectors sought to document it. This is when Grimm's collection of fairy tales were published, and the collection which included a German version of Chad Gadya (see here), with many other examples in the respective European nations. Suffice it to say, this is a 19th century genre. Schottky's recording of the legend of the Maharal and the castle is an example of this. Jews too were swept in by this trend, and they also began to print the folklore of the Jews, the popular legends which had not made it into the existing literature.

See how Berthold Auerbach wrote of whom told the the legend of the golem:

Chaya, the maid, an old woman. It was a bit of folklore, an old wive's tale. Auerbach is one of the first sources to put this story in print, in his 1837 novel Spinoza (above is an English translation from 1882).

The Jewish Romantics, writing in German, got it in the same way the others heard and then wrote down stories like Hansel and Gretel. This is why the story isn't in 'canonical' sources (ala Shu"t Chacham Tzvi) and why it appears exclusively in German in its original printed versions. It is remarkable that a story with such modest and humble beginnings eventually became a fundamental of faith. אל תטוש תורת אמך.

Here is the Chacham Tzvi's famous question concerning a golem:

He mentions that his ancestor (not grandfather) Rabbi Elijah of Chelm (also known as Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem) was reputed to have created a golem using the Sefer Yezira. Not a word about the Maharal. And why should there be? 70 years later the Chacham Tzvi's own great-grandson, Saul Berlin himself, also doesn't mention the Maharal's golem.

The question is, why doesn't Saul Berlin mention his own ancestor, Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, instead of Rabbi Naftali's golem? Here we have to guess, and my guess is that Berlin's own family was off-limits. Yes, he was mocking the concept that rabbis not only can but also did create golems, or more accurately the belief that the remains of a golem could yet be seen today, but he wasn't about to cite his own ancestor and drag him into the satire. Or maybe Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem himself could have been a target, having died 200 years prior, but mentioning him would have just drawn attention to the Chacham Tzvi, his father's grandfather. But I really don't know.

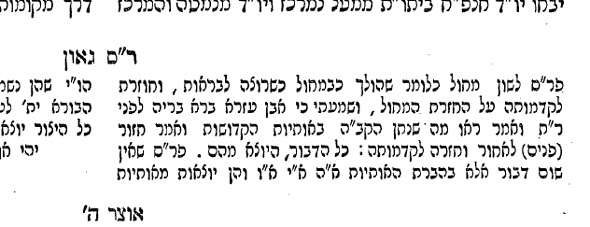

Incidentally, it seems that many believe that Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem was the Chacham Tzvi's grandfather. This is understandable, since he calls him זקני in the aforementioned responsum, and so does his son in Sheilas Yaavetz II.82:

However, think about this logically. How likely is it that Rabbi Elijah (1550-1583) was the grandfather of Chacham Tzvi (1656-1718)? How much older than you are your grandfathers? Are we to believe that the Chacham Tzvi's father was in his 70s when he was born? Not only that, his maternal grandfather, R. Elijah ha-Kohen of Alt-Ofen was born in 1616. That would mean that Chacham Tzvi's father was at least 33 years older than his own father-in-law! So logically this does not make sense, even though the Jewish Encyclopedia has Rabbi Elijah as Chacham Tzvi's grandfather, a mistake repeated in both relevant Wikipedia pages (here and here). It is also repeated in the text and the notes on pg. 150 in the very interesting Artscroll book Great Jewish Letters by Rabbi Moshe Bamberger (which I intend to review). What does Chacham Tzvi's son, Rabbi Yaakov Emden say about this ancestry? On pg. 4 of Megillas Sefer he writes:

אבא רבה הוא הגאון החסיד שבכהונה בעל ס' שו"ת שער אפרים ז"ל, ראש ב"ד בק' ווילנא המעטירה אז בהיות בשלותה, והיה לו כתב יחוסו עד אהרן הכהן, וחתן לאחד מן בני בניו של הגאון ר' אליהו בעל שמ הזקן ז"ל, שהיה אב"ד בקק' חעלם בימים ההם

In fact the Chacham Tzvi's paternal grandfather was married to the grand-daughter of Rabbi Elijah. Regarding Megillas Sefer, see here for a recent entertaining discussion about the provenance of this autobiography.

Next is a really interesting account of a golem. Commenting on Sefer Yezira 2:5, Rabbi Sa'adya Gaon writes the following:

"I have heard that Ibn Ezra created a creature before Rabbenu Tam and said 'See what God allows to be accomplished through his holy letters.'"

Rav Saadya lived 200 years before them you say? Hmm.

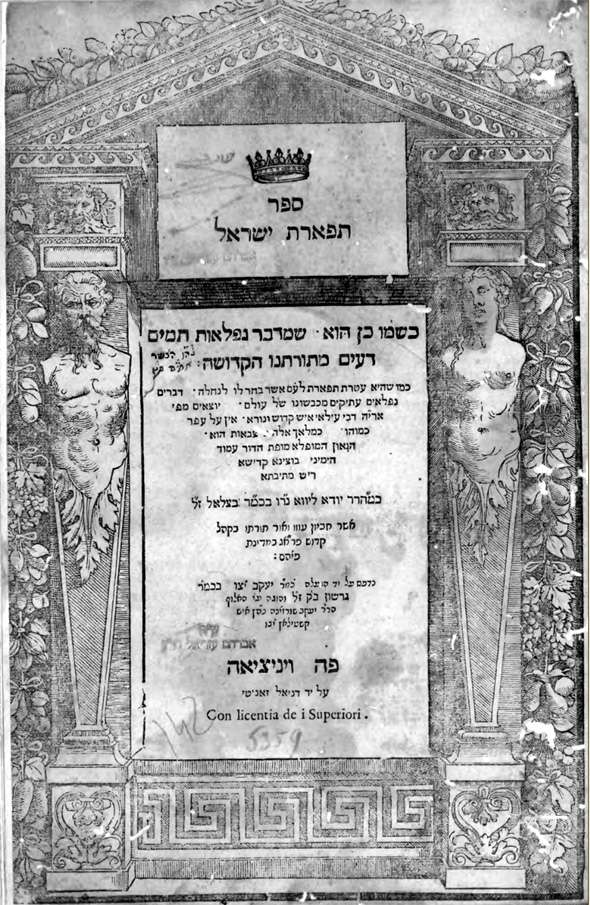

Since this is a Maharal post, it is worth glancing at the title page of his תפארת ישראל, published in Venice in 1599 (that is, ten years before the Maharal died):

I am not arguing anything about how the Maharal viewed such things, but facts are facts. There are many more such examples of nudes on the title pages of venerable seforim. Not only were they written by important rabbis, but in many cases we know who owned them (and who, therefore, did not deface them). A future post will show an interesting example of one such sefer owned by one rabbi with an extremely zealous reputation.

In 1989 there was a reprint of a commentary on the Torah by Rabbi Menachem Avraham Ha-kohen "Rapoport" (d. 1596).

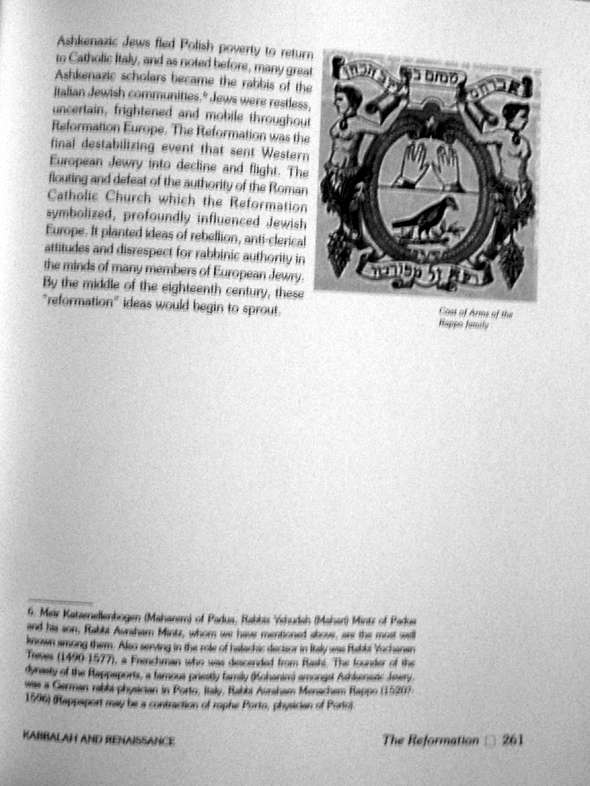

Toward the end of the second volume is a reproduction of the famous coat-of-arms of this family, except that the bare-breasted women are now wearing "shirts" (albeit tight ones!):

Here is the original, which

From Herald of Destiny by Rabbi Berel Wein:

Finally, a note about my discovery of the earliest known source for the Maharal's golem (link). It's a pity (for me) that it wasn't early enough to have made it into the impressive book Path of Life. Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel (cal. 1525–1609). In the relevant article by Byron Sherwin, "The Golem of Prague and His Ancestors" it mentions that for a long time it was thought that the first appearance of Rabbi Loew's golem was in an 1841 article by a non-Jew, with it appearing in Jewish sources beginning in 1847. However, he writes, Shnayer Leiman showed Jewish sources from 1837, and [I forgot!] showed non-Jewish sources from that same year. I showed one from 1836, written by Ludwig A. Frankl, a Jew. I'm under no illusion that this must definitely be the first written source. Earlier ones may yet be found. However the way in which I discovered this should be mentioned. I'm not going to pretend that I printed out pages of the Oesterreiche Zeitschrift für Geschichts und Staatsunde for some light reading. Rather, the discovery is a nice piece of fruit borne out of the digitization of literature. Who knows what truly important discoveries are yet to be found in overlooked literature?