Owen's book is a veritable how-to manual of textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible, occasioned by the atmosphere surrounding Benjamin Kennicott's project collating as many Bible manuscripts as possible with the aim of discovering the original ("primitive") uncorrupted text. The preface to Critica Sacra begins: "If the Hebraical Reader will give himself the trouble to observe and pursue these short Directions, he will find his pains in a little time sufficiently and amply rewarded. For he will be led hereby to discover and to correct many Errours in the Hebrew Text, which no other method of proceeding can so effectually enable him to perform. Nor is the benefit of the English Reader left wholly unregarded. . . " The book begins with a rule: "It may not be assumed as an allowed Maxim - That the Hebrew Scriptures have not reached us in that pure and perfect state, in which they were originally written - That they have undergone indeed many great and grievous Corruptions, occasioned by the ignorance or negligence of the Transcribers."

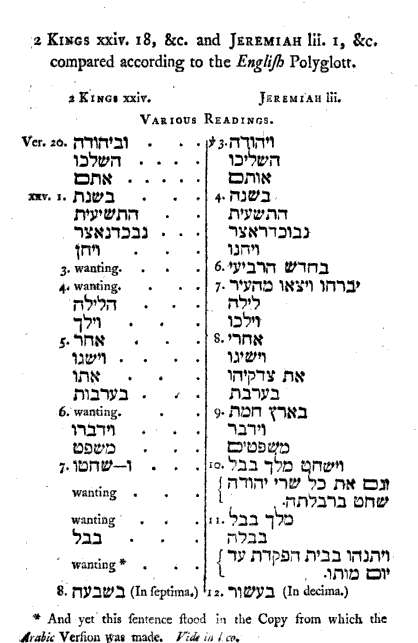

Here is one page, which lines up parallel passages in the Bible, showing what must be errors in transmission:

In short, this book sharply disagreed with the Jewish attitude toward the textual integrity of the Sacred Scriptures, and this Raphael Baruh sought to counter the notion expressed in Owen's maxim, by a careful examination of the book of Chronicles, set against parallel passages in the rest of Scripture. As there are indeed many discrepancies between Chronicles and the other books, this book was seen as in the sorriest state, full of errors. Baruh sought to demonstrate that Chronicles is in fact a kind of commentary on the other books, and what seem to be errors and mistakes are actually clarifications of one kind or another.

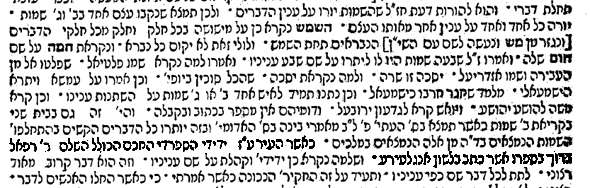

There's a reference to this book in Mordechai Gumpel Schnaber Levissohn's 1784 commentary on Ecclesiastes, תוכחת מגילה:

Below is Baruh's introduction, which is really quite fascinating, especially as a model for how to write persuasively. Owen's contention must have bothered Baruh far more than he lets on, but he writes moderately and modestly.