Briefly, the Parable Against Persecution is a story about Abraham written in the biblical style. Apparently Franklin was fond of asking for a Bible at dinner parties, opening it and then reciting his parable as the fictitious 51st chapter of Genesis.

The story is that a weary traveler comes to the tent of Abraham, who invites him as his guest, and feeds him. When Abraham saw that the man did not bless God, he questioned him about whom he worships. The man told him that he is an idolater. Abraham reacts angrily and tosses him out of his abode. That night God communicated with Abraham and asks him what happened to the stranger? Abraham replies that he doesn't worship you, so I drove him out into the wilderness. God tells Abraham that he himself has been providing for this man for 198 years, even though he is an idolater. But you can't provide for him for one night? Abraham immediately confesses his wrong and prays for forgiveness. Then he went into the wilderness himself to find the man, and brought him back and treated him kindly, sending him away in the morning with gifts. Then God tells Abraham, for your sin your descendants will be strangers in a foreign land for 400 years. But because of your repentance, I will redeem them, etc.

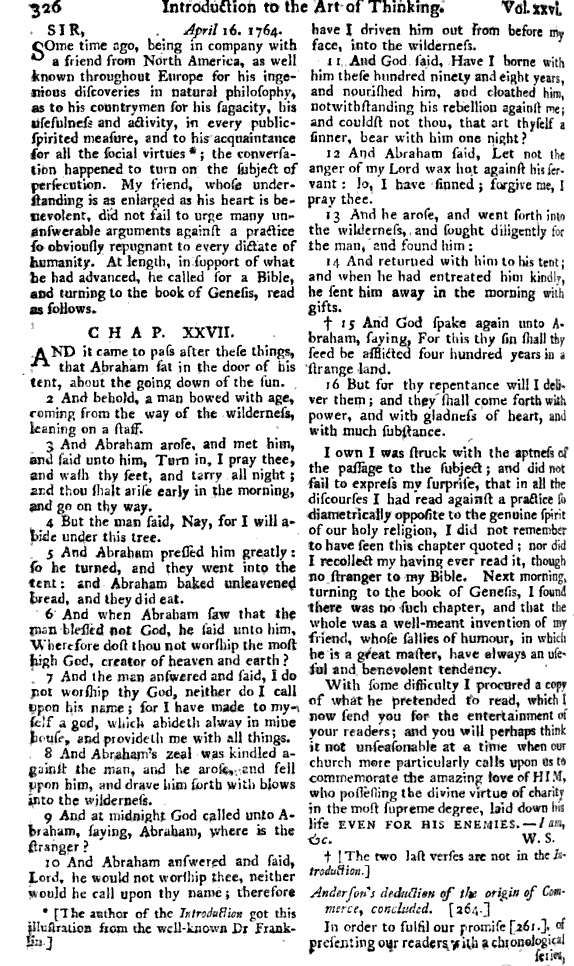

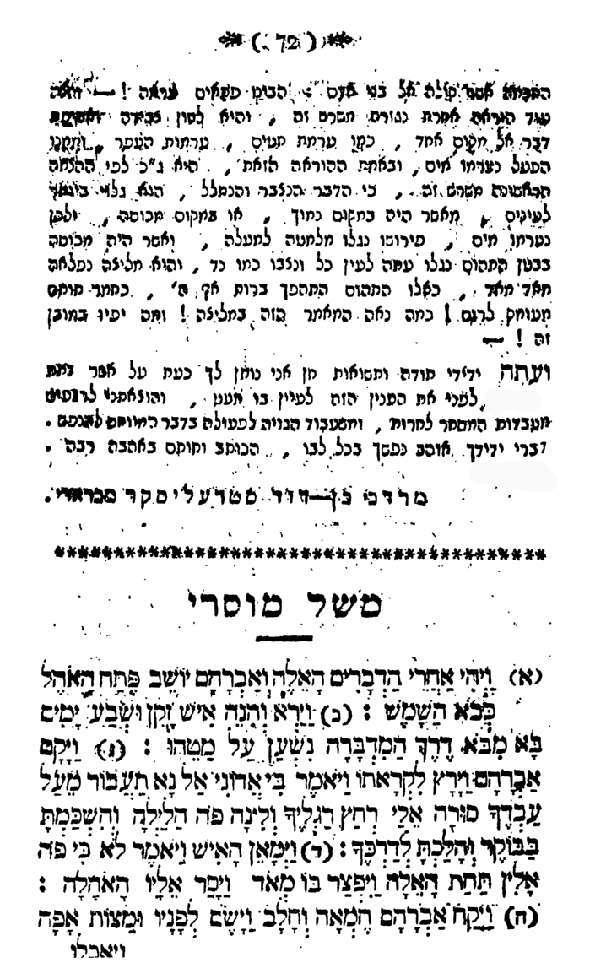

The parable was published in Henry Kame's Introduction to the Art of Thinking (1761). It is reproduced below from the Scots Magazine (1764) because the whole thing is included on only one page:

This particular story made a big splash in the 18th century, and it was reprinted many times, and probably repeated and even memorized. It was taken as yet another beautiful rational truth, presented by the ingenious Benjamin Franklin. Gradually it was discovered that although the style was Franklin's, the kernel of the idea was not his at all.

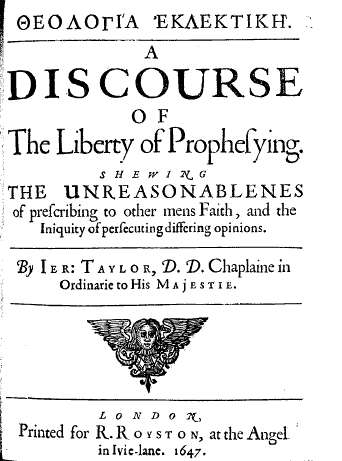

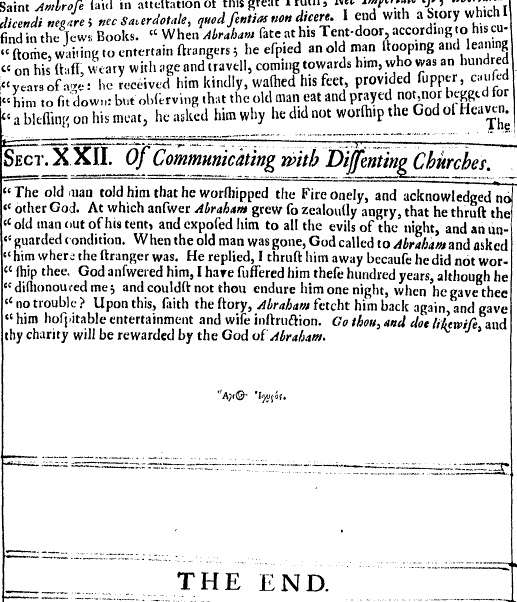

In fact a very similar story appeared in the end of the 2nd edition of Jeremy Taylor's The Liberty of Prophesying Shewing the Unreasonablenes of Prescribing to other Mens Faith, and the Iniquity of persecuting differing Opinions.(1651, I think - why it did not appear in the first edition, 1647, will be explained).

As you can see, this is essentially the same story, only it isn't rewritten as biblical prose. However, aside for Franklin adding 98 years to the man's age, there a specific detail in Taylor's which isn't in Franklin's. In the story we're told what kind of an idolater he is; he's a fire-worshipper (which sounds Zoroastrian, which is Persian).

Taylor writes that he "find[s] the story in the Jews' books." However, no one was able to discover which Jews' book, as it truly isn't in the Talmud or midrashic literature, although many readers are perhaps reminded of a well-known passage in Talmud Bavli Sotah 10a-b:

The truth is that Taylor did sort of find it in a Jewish book, but it's not part of the book itself, and it's not a Jewish story. In 1651 George Gentius published his Latin translation of Solomon ibn Verga's שבט יהודה under the title Historia Judaica. Here is the title page:

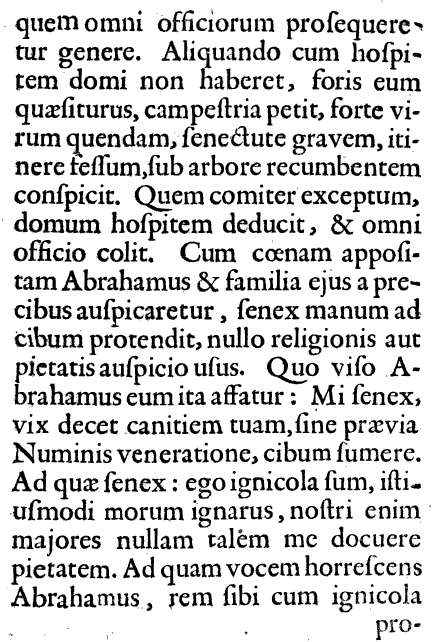

In the preface, in which Gentius dedicated the work to the rulers and people of Hamburg whom he says treat the Jews well, a version of this story is included, given in the name of Sadus (13th century Persian poet Sa'adi):

As it happens, Gentius had published his own translation from the Persian of the 13th century work Gulistan (Rose Garden) by Sa'adi in 1651, called the Rosarium Politicum of Musladini Sadi. He included a small story by Sa'adi in his other famous work, the Bustan (Orchard) in the preface to the Shevet Yehuda. Thus it is likely that Jeremy Taylor's "Jews' books" is actually the Latin version of Shevet Yehuda, the Historia Judaica published in 1651. This is why the first edition of Taylor's Liberty of Prophesying doesn't have this story at the very end; he hadn't read it in Gentius's book, since it hadn't appeared in print yet.

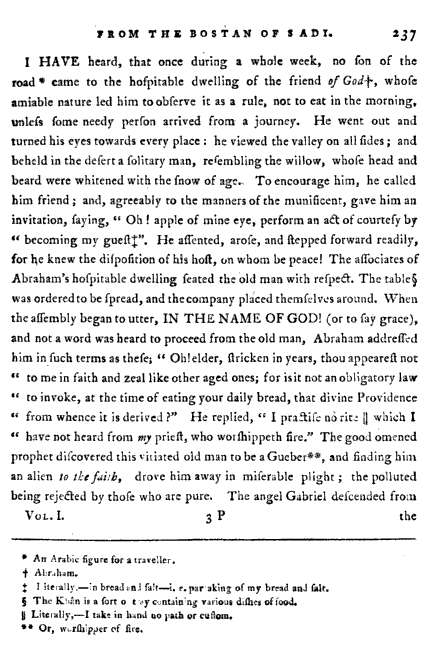

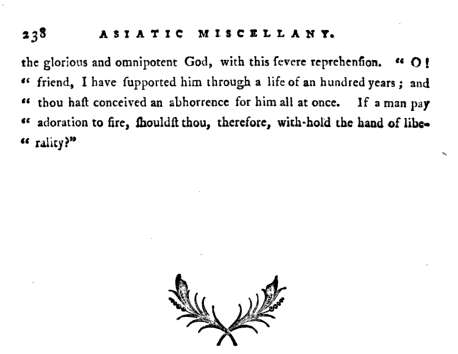

Getting back to Franklin, in 1789 a book called The New Asiatic Miscellany appeared, which all but accused Franklin of plagiarism (except that it sneered that he couldn't have gotten it from the original Persian and must have gotten it from a translation - the Taylor connection hadn't yet been made). The book included Franklin's parable, the original Persian of Sa'adi, and its translation into English:

At this stage of the game Franklin had become aware that he was being accused of plagiarism, seemingly from reading a review of the New Asiatic Miscellany in The Critical Review, and addressed it in a letter to Benjamin Vaughan on November 2, 1789:

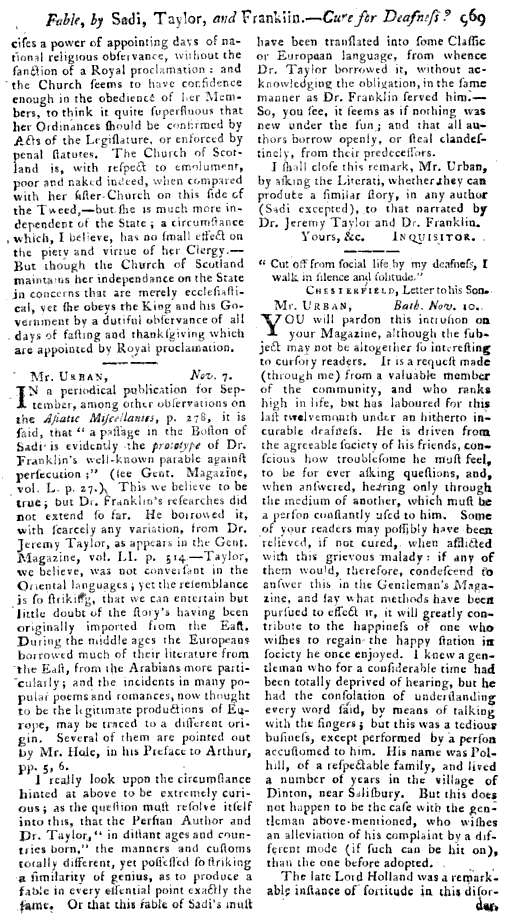

Discussion concerning the origin of Franklin's parable continued well after his death in April of 1790. In the November 1790 issue of the Gentleman's Magazine a writer signing his name Inquisitor (!) identified Franklin's source as Jeremy Taylor:

The connection of Franklin to plagiarism hardy went away. Here's a note from 1808:

Naturally there's a more Jewish angle to this story, but before I get to it, here are a couple of interesting references to Benjamin Franklin in 19th century Jewish literature:

In a note to the 2nd edition of Nachman Krochmal's Moreh Nevuchei Ha-zeman (1863) Letteris refers to Benjamin Franklin (pg. 13) in discussing another famous maskil of Lemberg, Menachem Mendel Lefin:

I must admit that my American pride flared up when I read of the חכם האנגלי האדון פראנקלין. But when you consider that Franklin was already 70 years old in 1776, I guess it's alright.

The second reference is only an aside, but highly interesting. Letter 19, pp.125-130 in Kerem Chemed 4 (1839) , by Lelio della Torre (הלל הכהן דעלאטאררע), co-professor with Shadal at the Collegio Rabbinico of Padua discusses Jewish names and naming practices. Toward the end he writes of something which he says was common in Italy of his day, that people name their children whichever non-Jewish name they like, and then they think of a Hebrew name which sounds similar, and give it to them as an afterthought so they can use it when they're called up to the Torah, or for marriage or divorce. Earlier he gives an example of Massimo for משה or Arnoldo for אהרן. He contrasts this with the pious British and Dutch people, who are proud to use Biblical names:

Once again, Franklin is English. I'm starting to get the impression that Europeans didn't really get used to the United States being independent from England very easily.

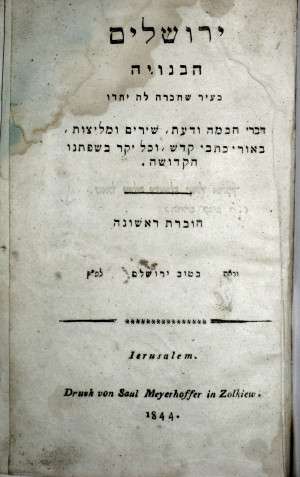

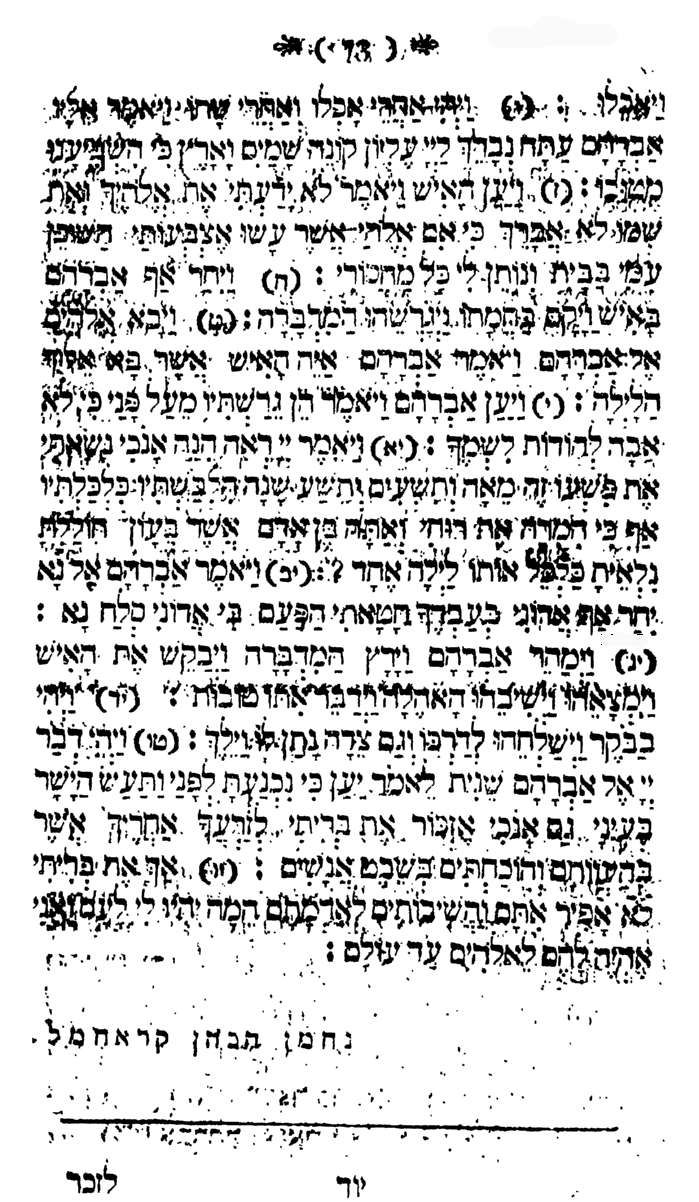

I imagine that Benjamin Franklin would have been pleased as punch had he lived to see that his Parable Against Persecution was eventually translated into Biblical Hebrew. In 1844 a periodical called ירושלים appeared in Zolkiew. It included a prose piece written in Biblical Hebrew style by Nachman Krochmal called משלי מוסר.

Although Franklin is nowhere mentioned, there is no doubt that this is a translation of the Parable Against Persecution. Although it is ironic that Franklin, who himself did not cite a source, is not given credit, I don't think anything should be made of that as Krochmal hadn't submitted it for publication, having died in 1841. This journal (only one issue appeared) was edited jointly by Jacob Bodek and Mendel Mohr, students of Krochmal (I described Bodek a little bit here). Likely the piece was found in a notebook of his, and perhaps no source was mentioned.

As far as I can tell, the 'discoverer' of this translation, that is to say the first one to read it who was likely to have made all the necessary connections, was George Alexander Kohut in a 1903 JQR article called Abraham's Lesson in Tolerance (Kohut was an American, knowledgeable in Jewish literature, and the son of a Persian scholar). In this piece Kohut conjectures that the reason why Sa'adi's story was thought to come from Jewish literature was because it first appeared in Latin in Gentius's translation of ibn Verga. Originally I had thought this was his original contribution, but then I noticed that the connection was already made in 1839, in the first volume of The Whole Works of the Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor. There Reginald Heber writes, among other things, that though he knew Taylor's source in Gentius, he initially had thought that "Sadus" was none other than Sa'adya Gaon (!) from the fact that Gentius calls him "venerandae," which seemed to him to be a translation of "Gaon." However, a friend pointed out to him that the correct identifiation is Sa'adi, not Sa'adya. Thus, it was that Taylor fell to "the common fate of those who quote at second hand, he ascribed to a Jew what his author had taken from a Persian," and that is why he thought Gentius was quoting a Jewish source.

Kohut's original contribution therefore was in bringing Krochmal into the equation. Kohut guesses that Krochmal had seen it in English or in German translation. I myself have no idea if he knew English, and German seems the better guess. For some reason Joshua Bloch, the author of the article on Nachman Krochmal in the Universal Jewish Encylopedia (v. 6 1939) feels justified in writing that "Benjamin Franklin's autobiography in the German version of A. von Binzer (Kiel, 1829) made a profound impression upon him." While this seems reasonably likely to have been where Krochmal had read the poem, I'm not sure how we know what impression the Autobiography made upon him!

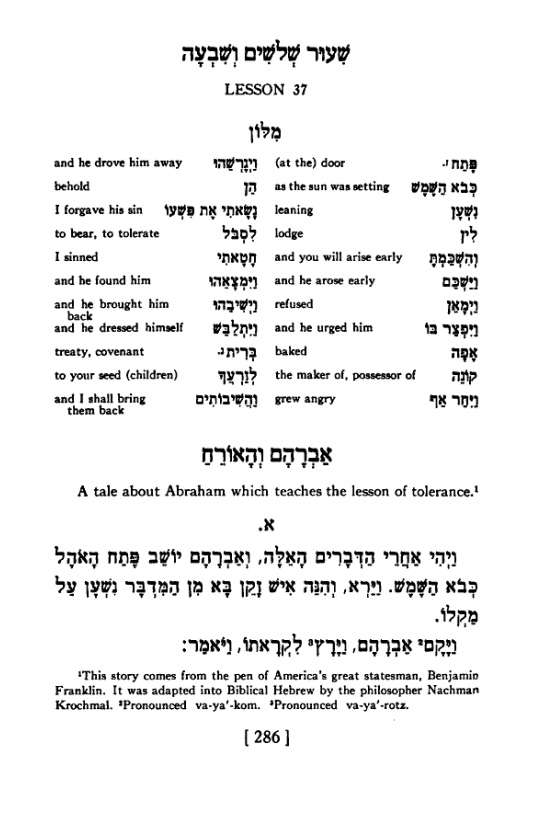

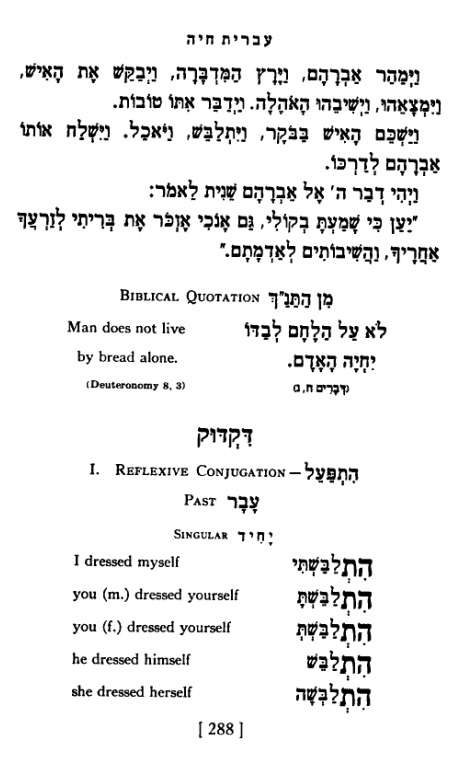

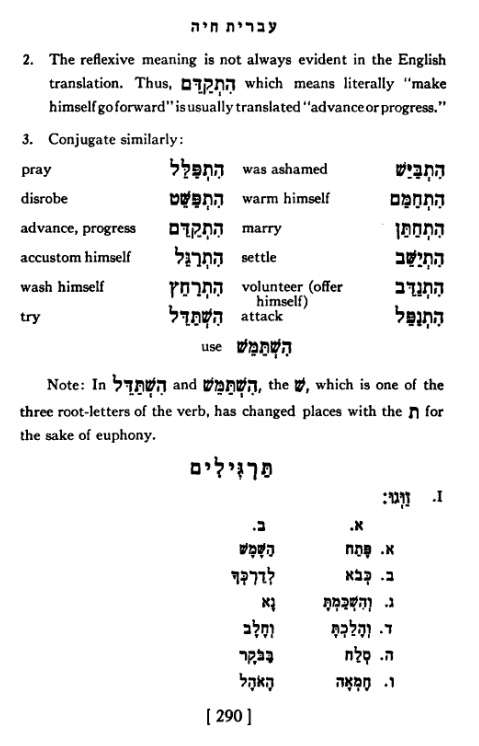

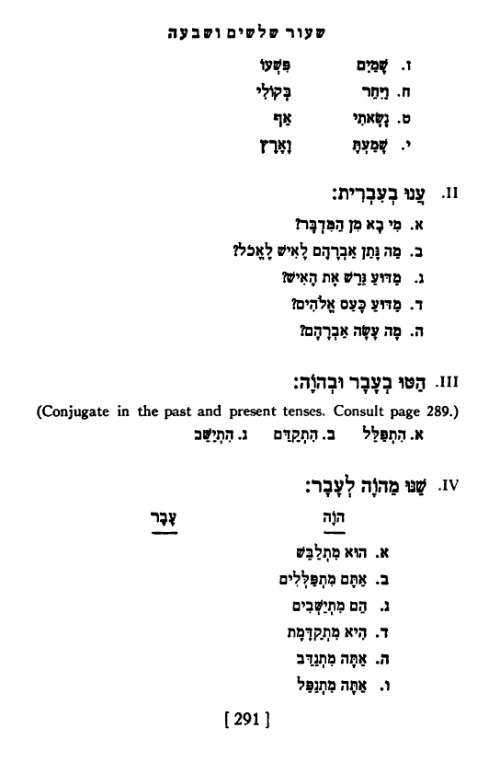

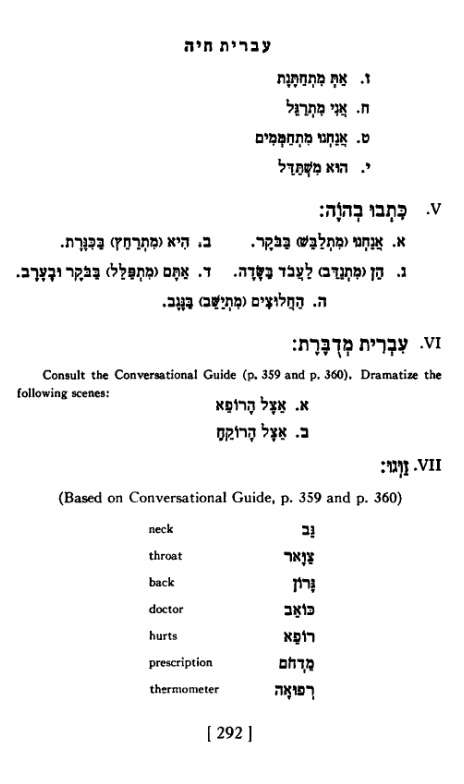

Interestingly, a Hebrew instructional book for students from 1952 included it, complete with its grammatical deconstruction: