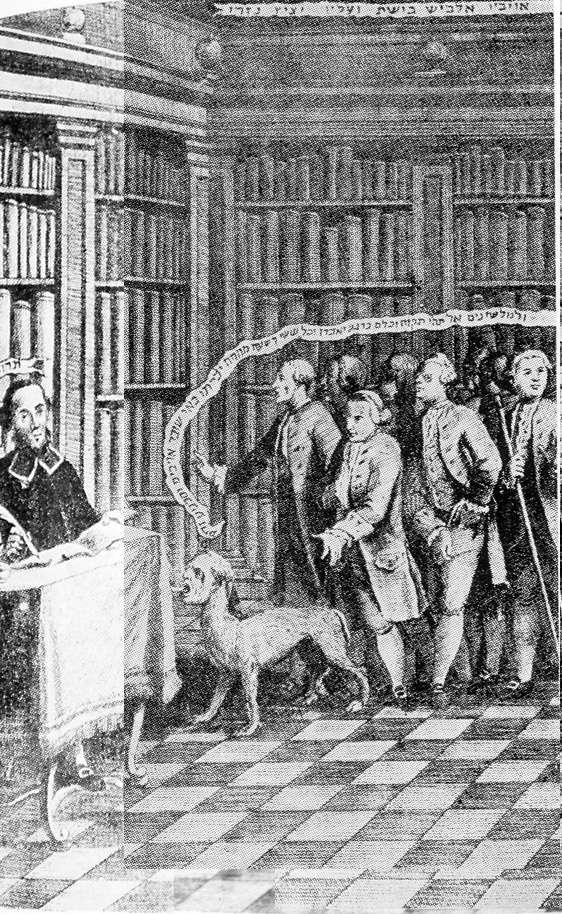

Here's an interesting picture of what that guy thought of the whole thing:

As you can see, here is an apparently pious and learned man seated with his seforim, being confronted by a gang led by a man with a dog's body (or is that a dog with a man's head?). There are some choice biblical (Psalm 132:18; Micah 5:8) and liturgical (link) quotes.

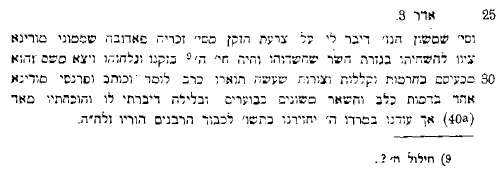

The background that I am aware of is as follows. This particular image was engraved in 1777, possibly by the man depicted himself. His enemies are the communal leaders of Modena, and he obviously got his pictorial revenge. Although there may be other sources which describe the circumstances (eg, in Modena communal records perhaps?) the only primary source I'm aware of comes about through a fortuitous coincidence someone told the Chida about it while he was staying in Trieste in March of 1777, where he also met the man. On pg. 88 in the Ma'agal Tov Ha-shalem we see:

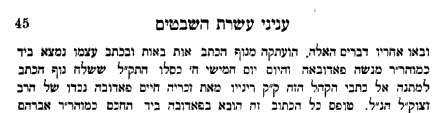

Chida writes that "The aforementioned Signore Samson [Levi] told me about the "plague of the beard," the Signor Zecharia Padova, whom the leaders of Modena ordered to remove his beard because he was "suspected" and was causing a chillul Hashem (profanation of God's name) and they shaved it off. He left there cursing them and with a caricature that he made, of himself as a rabbi studying, and the officials of Modena, one of them with the head of a dog and the rest appearing like boors. At night I spoke with him, reproached him a great deal, but he remained rebellious. May God allow him to repent for the honor of his rabbinic ancestors." Thus we know what the circumstances of this very interesting caricature are, even if we do not have very specific details.

In Benjamin Cymerman's English translation of Ma'agal Tov he footnotes that "He is clearly a dubious character and would shame the community," which I suppose is the only conclusion one can draw from this passage. Of course we realize that Zecharia Padova did not see it that way, quite the opposite; I do not know who is right in this dispute. It should also be noted that without further information it isn't even possible to conclude that the communal leaders over-reacted. In that very year, 1777, the Jews were expelled from all territory of the Republic of Venice (link). While it's obviously too much to lay unspecified bad behavior on the part of one individual as imperiling the entire community, especially when we do not know if this was even claimed on the part of the officials, we would do well to recall at least that 1777 wasn't 1977, even in Italy.

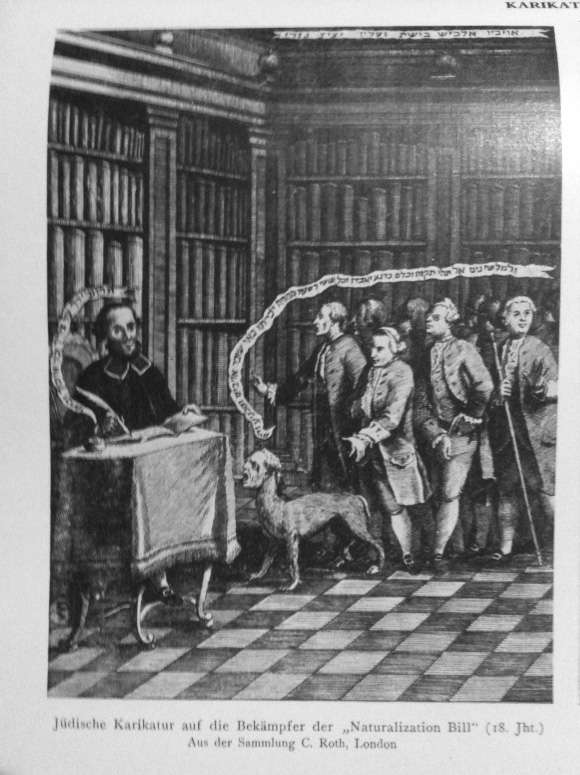

I don't know how many copies of this picture were distributed or how many survive, but this particular copy was in Cecil Roth's personal collection and he printed at least two times. The first appeared in the the pre-Hitler Encylopedia Judaica [1]. Roth had sent the editors the image but to his dismay they completely messed up the caption. Writing in the 1940s, Roth said that "as it happens, this caricature — a unique copy, probably, of a unique production — is to be found in my collection, answering in every detail to Azulai's description. When the Encyclopaedia Judaica was in the course of publication, I sent it to the Editors for reproduction. To my amazement, they described it (volume ix, c. 967-8) as a caricature on the English "Jew Bill" of 1753, thus depriving it completely of its significance. I am happy to have this opportunity of clearing up the confusion." [2]

Below is how it appeared in the Encylopedia Judaica:

Here is how Roth described the image: "The great Azulai, in his travel-diary Maagal Tob (p. 88) mentions how in 1777, when he was in Trieste, he heard about the dispute in which this person had been involved with the leaders of the community of Modena, and how in revenge he had distributed far and wide a caricature shewing himself as a Rabbi, sitting at his desk and writing, and his enemies looking like boors, one of them in the semblance of a dog. " I want to include another comment by Roth, because it shows his humility. Anyone who will go on record admitting that he doesn't understand something and asks for help is deserving of recognition for it: "(I may mention that Azulai's allusive method renders parts of the passage unintelligible, and that I would be most grateful for any assistance in interpreting it.)"

Taking Roth up on the challenge, another writer writes that he doesn't believe the Chida meant to say that Zechariah Padova made the image himself. "Azulai uses the verb עשה which can mean not only to make something but also to have something made. It is more likely that the Rabbi would have gotten others to compose the caricature than that he would do it himself. The caricature is a copper engraving the execution of which must have required considerable acquaintance with the subject." [3] While he is probably right about that, he refers to the subject of this post as "Rabbi Zechariah Padova" and "Rabbi Zechariah" and "the Rabbi."

In a book edited by Roth in 1961 called "Jewish Art, an Illustrated History" once again this image is printed (pg. 522) in an article by Roth himself called "Jewish Art and Artists Before Emancipation." Evidently Roth did not accept this clarification, for he writes (pg. 521) "In 1777, a scholar from Modena in Italy, Zechariah Padova, after a quarrel with the leaders of his community, caricatured them in an etching, in which he depicted himself seated in his study and his elegantly-dressed opponents advancing on him, one of them — his bitterest enemy — having a dog's body. The artist's self-portrait is noteworthy." In the next paragraph he calls this an "unusual achievement."

It is true that Roth never calls him a rabbi, but Lansberger did, and I was naturally curious about his identity. Let me tell you, there isn't a lot out there about Zechariah Padova.

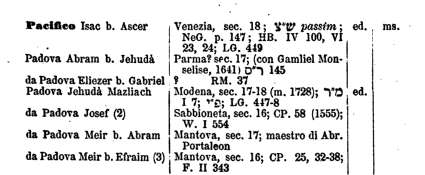

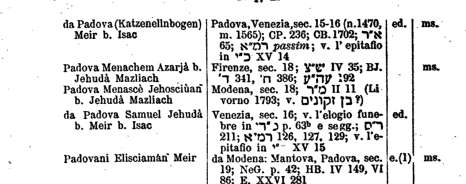

In a remarkable little book which essentially lists any and all Italian rabbis through the ages called Indice alfabetico dei rabbini e scrittori israeliti di cose giudaiche in Italia (1886) by Rabbi Marco Mortara we find the following entries for rabbi surnamed Padova; thus we see that he was not a rabbi:

Here is the title page of that book:

The only possible reference I found to our Zecharia Padova is the following in the 4th volume of the Mekize Nirdamim Society's Kovetz al Yad series (1888). This particular volume published documents relating to the Ten Tribes by Adolph Neubaeur:

As you can see in Mortara's book, one of the Rabbis Padova was Rabbi Menashe Padova of Modena (d. 1793), or Menasce Jehosciuan Padova in the charming Italian orthography. If this Zechariah Chaim Padova, the grandson of Rabbi Menashe Padova, is the same man then we've seen what the Chida was talking about; he was part of a distinguished rabbinic family, and the Chida felt that he was defaming his family. If only we knew what he was accused of!

[1] I guess a lot of people don't realize that Encylopedia Judaica was originally begun in Germany (and naturally, in German). Ten volumes were published (Aach to Lyra) between 1928 and 1934 until the project had to be abandoned. The publisher Nachum Goldmann was instrumental in reviving the project in 1966, and the fruits were the Encylopedia Judaica, edited by Cecil Roth, which many of us know and love (completed in 1972). This complete EJ even included some articles translated from the original German edition. My thanks to Dan Rabinowitz for providing me with the page from the Encyclopedia Judaica.

[2] Roth, Cecil "New notes on pre-emancipation Jewish artists" pg. 506 in HUCA 17 (1942)

[3] Landsberger, Franz "New studies in early Jewish artists " pg. 301 HUCA 18 (1944). I am happy to send these two articles to all who email me and ask.