In this excerpt, the priest Simeias asks the rabbi Abraham ibn Maimon "Wilt thou now explain to me the meaning of the song which begins "Khad Gadya--A Kid, &c.;" and of the other, "Ekhad mi yodea--The number One, who knows what it signifies?" The rabbi Maimon replies as follows: "The origin of the song Khad Gadya is, or should be, well known. I have read the song in a German almanack, in which it is printed, with other amusing songs, in the old German language, under the title of Das Zeiglein, and arranged in verse to suit the fancy of children : it is printed exactly as in our Passover service, with the exception of the stanza which begins with the words "And the slaughterer came;" which was probably composed by the person who translated the song from the German into Hebrew. That this song is of German origin is corroborated by the fact that it is not to be found in any ancient edition of the Passover service. Doubtless the German Israelites were accustomed to sing it for the recreation of their children, and to keep them from going to sleep on the Passover evening, long before it was printed ; and when it was printed, thought that it would be judicious to make it expressly a part of the Passover service. At the present day we find it in some of the prayer books used at the Passover, written in the old German language." For much the same reason as the proceeding, the other song was introduced into the Passover service; "Ekhad mi yodea;" . . .

Interestingly enough, the English translator of this book inserts here a footnote objecting to this account of the origin of the song, arguing that it is far more profound than a mere children's ditty meant to keep them awake. He cites an allegorical interpretation which he read in the Haggadah Arba'ah Yesodos (Amsterdam, 1783 and Offenbach, 1788) which you can read, along with its interpretation of Chad Gadya, here (or here for the 2nd edition).

Indeed, what is the origin of the song Chad Gadya? Is it as Maimon, speaking through Levinsohn, presents it? Furthermore, where did he "read the song in a German almanack, in which it is printed, with other amusing songs, in the old German language, under the title of Das Zeiglein, and arranged in verse to suit the fancy of children?" I would say at one time the evidence seemed to point to it as clearly the case, but now it's less clear. Since we have no recordings from hundreds of years ago, we must look for it in writing. It is accepted without controversy that the first printed Haggadah which included Chad Gadya was the Prague edition of 1590. It seems notable that the Prague edition of 1527 did not include Chad Gadya. Absent any other evidence, one could speculate that the song either came into existence some time between 1527 and 1590, or at least had been deemed worthy only in 1590 of something which it was not yet in 1527, namely inclusion in a printed Haggadah. Both editions of the Haggadah can be viewed at the JNUL Digital site here and here. In either event, it seems certain that there aren't mounds of earlier manuscripts with the song, so while it may have already existed considerably earlier than either of those dates, unless it was a vast oral secret it probably wasn't even close to the standard part of the seder as it came to be in the 400 years since its first publication. But are their earlier manuscripts? Continue below.

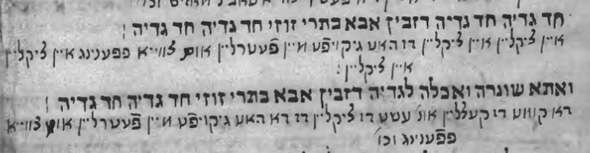

The 1527 Prague Haggadah ends with the familiar songs, Va'amartem Zevach Pesach and Ki lo Na'eh, followed by Chasal Siddur Pesach. Both Echad mi Yodea and Chad Gadya are not to be found. Take care to look at the JNUL copy, because after the last page someone added by hand both of these songs, along with a "Yiddish" translation (presumably the fellow who wrotes "ani Elya bar Yona kat"z [?] on the blank page preceding). Unfortunately there is no date, so its not known if these hand written songs were added some time after 1527 or much later, after 1590.

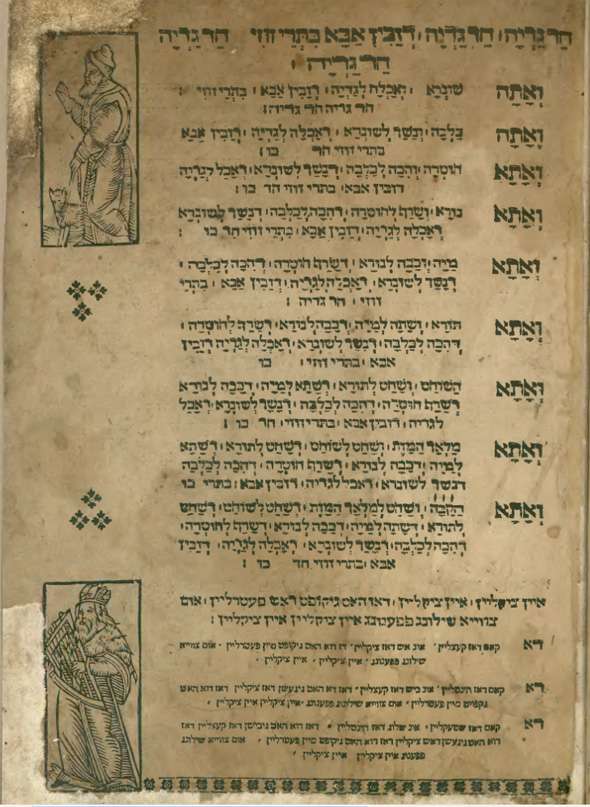

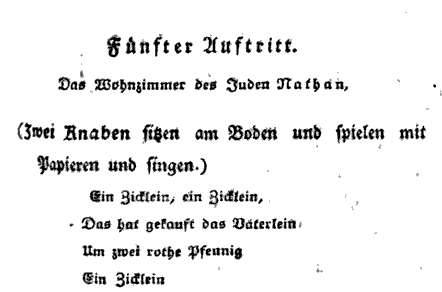

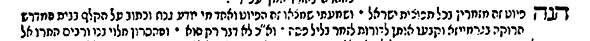

Next is the 1590 Prague Haggadah, which has Chad Gadya in print for the very first time and it looks like this:

Here is the song in its present Aramaic text, with its German-Yiddish translation, Ein Zicklein. As you can see, the song also translates the Aramaic currency zuz as schilling pfenning, which I think is pretty cool (in case it isn't obvious, the currency terms "shilling" and "penny" come from these German currency terms). Below is the hand-written one added to the 1527 edition. Here zuz is just pfenning, so make of that what you will in terms of which one is earlier:

Thus far for early printed editions. In 1805-08 an influential three volume collection of traditional German folk songs was published under the title Das Knaben Wunderhorn. The authors were collectors of folklore who went around recording (in writing) oral traditions and folk songs. The purpose of these volumes was to instill a romantic sense of peoplehood amongst the German speaking people. This movement was broadly known as the Völkisch movement, essentially a German offshoot of the wider Romantic movement which was all the rage in Europe in the early 19th century. One guess how Jews generally fit into Romantic European schemes of the time; it should be noted, however, that there were Jewish Romantics too. Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and Samuel David Luzzatto can probably both be described as such each in their own way.

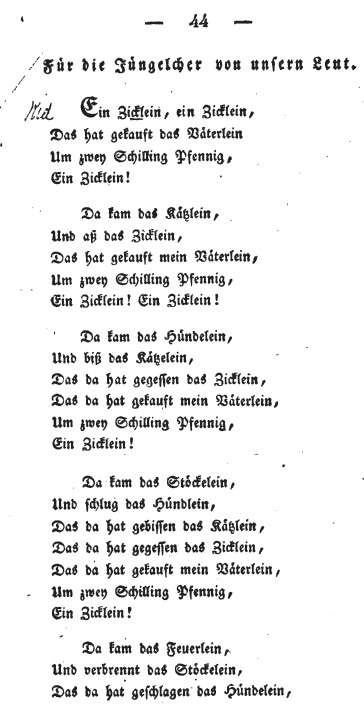

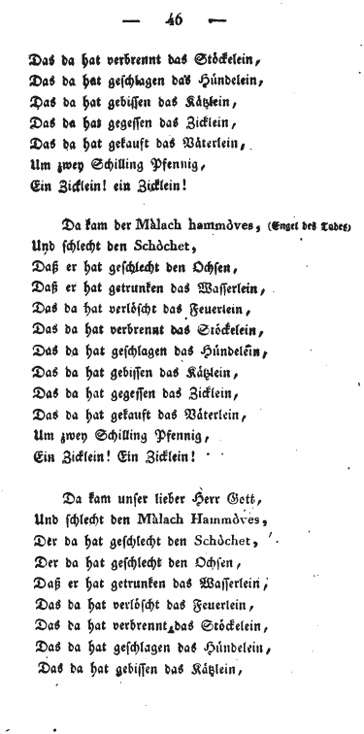

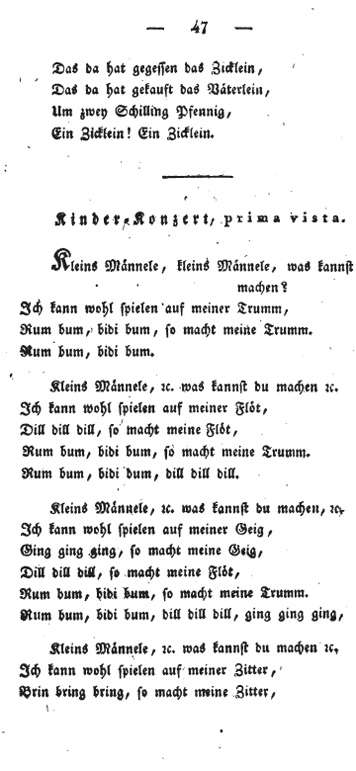

In the third volume a song called For the Youngsters of Our People appeared:

As you can see, this is but a German version of Chad Gadya. Or was it? Might not Chad Gadya be an Aramaic version of Ein Zicklein? I am sure the astute reader notices right away that this German folk poem für die Jüngelcher von unsern Leut features characters called "der Schochet" and "der Malach hammoves" both of which are written in Latin not Gothic letters and translated for the reader's benefit. The compilers of the Wunderhorn do not give a source for this song, but presumably it is an authentic piece of oral folk culture. It cannot be pristine, however, because it includes the aforementioned Hebrew terms (actually, its inclusion makes its authenticity highly likely), which means that it cannot be entirely independent from the Jewish version. One can only guess if it entered the German children's canon through the scores of Jewish converts who went on to marry and raise Germanic Christian families. However, it should also be noted that the Jewish version of Chad Gadya was far from unknown to Christians before 1808. The Jewish Encyclopedia entry for Chad Gadya includes no less than 5 Christian treatments of the Pesach song raging from 1699 to the 1740s. In addition to the above, one scholar thought that its Jewishness can be shown by the term "unsern Leut" "our people" which she claims was a particularly Jewish expression used by German Jews ("unsere Leut"). Finally, one of the collector-editor's of the Wunderhorn, Achim von Arnim actually included a snippet of this song in his 1811 play Halle und Jerusalem in an obviously Jewish context (with slight changes: here instead of two "Schilling Pfennigs" it's two "red cents"):

In 1836 Leopold Zunz published a highly influential book about the history of Jewish semons called Die gottesdienstlichen Vorträge der Juden in which he noted that the four final songs in the Haggadah are not found prior to the 15th century. He calls Chad Gadya "einem deutschen Volksliede nachgeahmte," or a copy of a German folk song, although he does not explicitly refer to the Wunderhorn or other such songs (perhaps he means to say that the Aramaic was translated from the German as it appeared in the 1590 Prague edition and elsewhere).

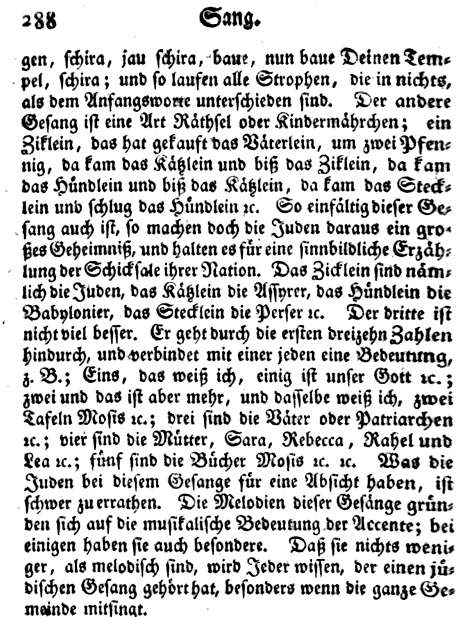

Levinsohn does not give Zunz as his source, although he certainly must have read it. He only mentions a German luach ("almanach") . It doesn't sound like the Wunderhorn; nor can I think of a reason why Levinsohn would have read it. However, I did find the following from a German Enclyopedia of 1824:

While not an almanac, it's just close enough in time that it gives an illustration of the sort of thing he might have read it in. However I would just highlight that Levinsohn writes that the version he saw went up to the "the slaughterer." He assumes that whomever translated it from German to Aramaic added that stanza, and the two which follow it. I wonder if the reason why the version he saw did not include the last three is because its source was the Wunderhorn, which included the Hebrew in two of the final three verses. Perhaps whomever it was that republished it wished to hide its Jewish origin; conversely, perhaps they wished to obscure that the source for it could not be definitively established as non-Jewish. These facts may have been a fly in the ointment for whomever sees it as an obviously German song originally. Note: in the 1590 Prague Haggadah even the German-Yiddish translation uses the Hebrew. Thus far there seems to be no German version of the song without Hebrew:

I mentioned at the start that the first printed edition of the song is from 1590, with it appearing immediately in Aramaic and German-Yiddish. But obviously the editor of the Second Prague Haggadah had a source himself, so the song (one or both versions) is surely older, even if at first blush a case might be made that it wasn't as old as the first Prague Haggadah. However, Zunz dated it to the 15th, not 16th century. His source might have been the following, first pointed out explicitly I think by Kaufmann Kohler in an 1889 article. In 1791 a rabbi named Yedidya Thia Weil (1721-1805; his father was the author of Korban Nesanel) published a Haggadah with his own commentary called Ha-marbeh Le-saper. After Chad Gadya he appends a note (its on pg 47 of the hebrewbook.org pdf):

As you can see, he prefaces his remark that Chad Gadya is no mere ditty with the remark that he's heard that this poem, along with Echad mi Yodea, was originally found in a manuscript in the Beit Midrash of R. Eleazar Rokeach of Worms (1176 – 1238). Here he does not say anything more about the manuscript, such as its age. However, this Beis Midrash is known to have burned in 1349, being rebuilt during the following five years, and one scholar assumed that if the manuscript existed in the original Beis Midrash then we can say that the song existed in the first part of the 14th century, if not as far back as the lifetime of the Rokeach himself (13th century). However, this is obviously a slender reed (who says it wasn't in the rebuilt Beis Midrash?). Weil writes elsewhere that he used a siddur written in 1406 as a help in writing his commentary. Thus, if this siddur was his source for the statement about Chad Gadya being in a manuscript in the Worms Beis Midrash, we can at least say that in 1406 there was such testimony (I'm given to believe that Rabbi M. M. Kasher discusses this in Haggadah Shelemah, which I didn't see). This of course means that the song was known to exist in 1406.

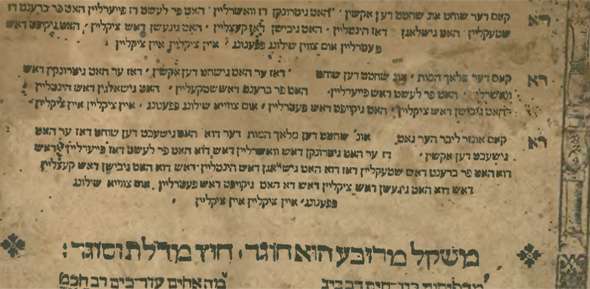

While these kinds of speculations and feats of reasoning are fun, it seems that there is some hard evidence which places the song as early as the 15th century. The Yiddish linguist Chone Shmeruk discovered a 15th century manuscript of the song in Aramaic and German-Yiddish. As a point of interest, Shmeruk believed he was able to demonstrate that the Yiddish was the original, and the Aramaic the translation. I haven't seen his paper, nor do I possess the skills necessary to form an opinion. Below is a highly interesting variant stanza as it appears in Shmeruk's 15th century manuscript:

ואתא עכברא דאכל לגדיא דזבין אבא בתרי זוזי חד גדיא חד גדיא

דא קאם מייזליין און עשיט דז זיקליין דש קאפיט דז אלט וועטירליין אום צוייא פפעניגליין איין ציקליין איין ציקליין

דא קאם מייזליין און עשיט דז זיקליין דש קאפיט דז אלט וועטירליין אום צוייא פפעניגליין איין ציקליין איין ציקליין

And along came the mouse that ate the goat that Father bought for two pennies, One Little Kid, One Little Kid

The mouse?! That has to be some scary mouse to eat a goat. Naturally the cat follows.

(Note also that in this manuscript we don't read of "schilling pfenning" but "pfenniglein," which is closer to the hand-written version appended to the 1527 edition mentioned earlier.)

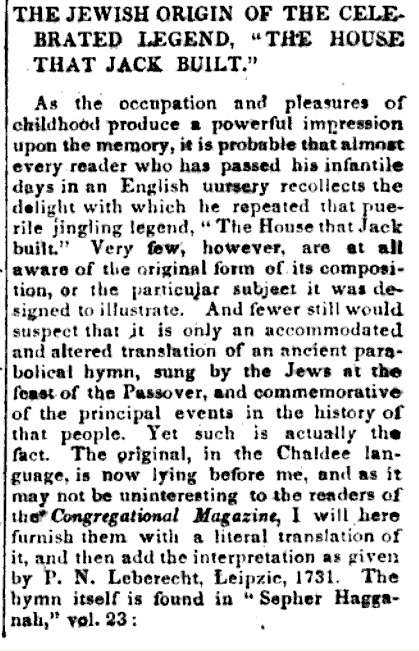

One more thing to note: Jewish scholars naturally begin with Chad Gadya, and in noting the many many parallels in other cultures and literatures (which I could not even begin to get into) they tended to assume a Jewish borrowing. Non-Jewish scholars, by contrast, began with the parallels and they tended to assume a borrowing from Chad Gadya. Make of that what you will. See below for an early 1830s article which opines that there is a "Jewish Origin of the Celebrated Legend "The House That Jack Built":

In a lecture called "Jewish Diffusion of Folk-Tales" Israel Abrahams writes

If we were to trust some writers on this subject, our hands would be more than full with materials. Attempts have been made at various times to show that all, or nearly all, folk-tales and fables, all the phantasmagoria of popular fancy, can be tracecs to Jewish sources. I have a lurking sympathy with such views, as I trust I have with all that is youthful and enthusiastic. I was young myself in this sense not so many years ago, and had a tendency to cry " Cherchez le juif" in all investigations into origins. To see in all philosophy only the influence of Philo, Ibn Gebirol, Maimonides, and Spinoza, to trace all mysticism to the Kabbala, to see in medieval science only the work of the Jewish translators, and in mediaeval exegesis only the influence of Philo, Rashi, Ibn Ezra, and Kimchi— these are the temptations which assail the young Jewish investigator when he first comes to appreciate the solid contributions to human knowledge and insight which must for ever be associated with these names. But soberer thoughts come with wider knowledge, and we learn to look upon Jews not as monopolists, but as co-operators in the grand work of building the mighty fabric of human knowledge.While there is much to agree with in the above, I would just note that "it is well known" is not hard evidence even if occasionally that is how it masquerades.

Scientific caution is especially necessary in the particular branch with which we are at present concerned. At first sight it seems only natural, when we find a popular tale or superstition first mentioned in a Jewish source, to trace all other occurrences of it to this. But both the Jewish and the other may have been derived from a third and earlier source, and we may be mistaking the relation of cousinship for that of paternal affiliation. Thus to take a familiar example. In Mr. Halliwell's collection of " Nursery Rhymes and Tales" the history of "The House that Jack built" is gravely traced back to the familiar "Chad Gadya" of the Haggada Service, and Mr. Clouston follows his lead in his recently issued " Popular Tales and Fictions," calling the Haggada a part of the Talmud. Yet it is well known that the "Chad Gadya" itself was derived from a German " Volklied," and only appears in later MSS. of the Haggada.

. . .

We have then to be very careful in tracing any popular tale to Jewish sources as its original, and even when we have, there is always a presumption against the Jewish being the original origin, if we may so be tautological. For how are such stories spread ? In friendly chat by the fireside, in convivial gatherings, on occasions of family rejoicing and the like? Alas! there have been but few periods or places in Jewish history where Jews could join in these gatherings, and contribute their quota of instruction and amusement. Our oral tradition has been almost entirely amongst ourselves, and in seeking for any traditions which Jews may have handed on to their neighbours we must look to books. Though common folk avoided Jewish society throughout the Middle Ages, scholars and students always had a hankering after the " wisdom of the Hebrews," and in each age some sate at the feet of the Rabbis. But they chiefly sought them for instruction in theology, and the only folk-tales likely to have spread in this way were those about the Old Testament characters. It was, of course, in this direction that Jewish imagination took its main flight, and many, if not most, of the legends about Old Testament characters can be traced directly or indirectly to the Midrashim. In particular, all the Biblical legends of Mohammed can be traced to this source, as many scholars have shown.

ETA: Please see Eliezer Brodt's fantastic post from 2007 on the Weil Haggadah and its author.

I also wanted to add a note on the unusual name Tia (טיאה; at least it's unusual now). Tia was a kinui, or nickname, for his Hebrew name Yedidya, a common practice at the time. For example, a man might sign his name Shlomo ha-mechuneh Zalman, Shlomo, nicknamed Zalman, or Yehuda ha-mechuneh Leib. Everyone would call him Zalman or Leib, and so forth. Similarly, Rabbi Yedidya Tia Weill was actually known as Tia Weill. However, it seems to me that Tia is Theo. What's the connection between Theo and Yedidya? The answer is simple, but as a preface I'd like to note that the famous Philo of Alexandria wasn't so famous among Jews until Rabbi Azarias de Rossi introduced him with the name Yedidya to a Hebrew-reading Jewish public in his Me'or Enayim. Philo, meaning friend or lover in Greek, seemed to him to be appropriately rendered as Yedidya, friend-of-God, in Hebrew. In Leopold Zunz's interesting and ground-breaking (and politically motivated) study of Jewish names, Named der Juden, he writes (pg. 31) that Yedidya and Theophilus are equivalent. It's anyone's guess why the -phil was dropped in the Yiddish name Tia/ Theo, but it seems an appropriate equivalent to Yedidya no less than Zalman for Shlomo or Leib for Yehuda.