New Jewish Encyclopedia:

Torat ha-Olah (Prague, 1570), a philosophic conception of Judaism. In his work he endeavors to give Jewish philosophy and thought a kabbalistic basis and to establish their inner identity, maintaining that they merely used different terminology. He also explains the meaning of sacrifices and the measurements of the Temple and their symbolism.Jewish Encyclopedia:

His works of a philosophical character are "Meḥir Yayin" (Cremona, 1559) and "Torat ha-'Olah" (3 vols., Prague, 1659). The former is a philosophical work in which he treats the Book of Esther as an allegory of human life. The "Torat ha-'Olah" is a philosophical explanation of the Temple, its equipment, and its sacrifices. In the description of the Temple, Isserles follows Maimonides' "Yad," Bet ha-Beḥirah, even in those cases where Maimonides is in conflict with the Talmud ("Torat ha-'Olah," I., ch. ii.). According to Isserles, the entire Temple and its appurtenances—their forms, dimensions, and the number of their parts—correspond to things either in divine or in human philosophy. For instance, the seven parts of the Temple (ib.) correspond to the so-called seven climates. The women's courtyard and its four chambers correspond to the active intelligence and the four kingdoms, mineral, vegetable, animal, and rational, which receive their form from the active intelligence ("Torat ha-'Olah," I., iv., vi., viii.). He also follows Maimonides in many philosophical points, as, for example, in a belief in the active intelligence, and regards the angels not as concrete bodies, but as creative; every power of God being called "angel" (messenger) because it is an intermediary between the First Cause and the thing caused or created (ib. II., xxiv.; III., xvii.; comp. "Moreh," ii. 6).

In many other points, however, he differs widely from Maimonides. He follows in fixing the number of the articles of faith or fundamental principles ("'iḳḳarim") at three; viz., belief (1) in the existence of God, (2) in revelation, and (3) in divine retribution. To Albo's six derived principles Isserles adds three: free will, tradition, and the worship of God alone ("Torat ha-'Olah," I., xvi.). Belief in the creation of the world is in his eyes the most important of the derived principles; and he refutes the seven arguments of the philosophers against it (ib. III., xliv., xlv., lxi.). He does not, however, consider it necessary to believe in the end of the world (ib. ii. 2)—another point on which he differs from Maimonides (comp. "Moreh," ii. 27). Albo

As Isserles lived at a time when the Cabala predominated, and as he was a contemporary of Isaac Luria, Ḥayyim Vital, and other cabalists, it was natural that he should be influenced by mystical views. Although, as has been already said, he was opposed to the Cabala, he devoted a part of his time to its study. His "Torat ha-'Olah" is full of cabalistic opinions. He appreciated the Zohar, believing it to have been revealed from Mount Sinai; and he rejoiced when he found that his philosophical views were confirmed by it ("Torat ha-'Olah," I., xiii.; II., i.). He occupied himself, too, with the study of (ib. I., xiii.), and believed that a man might perform wonders by means of combinations ("ẓerufim") of holy names (ib. III., lxxvii.). But he refutes the cabalists when their opinions do not agree with philosophy. In general, Isserles endeavored to prove that the teaching of true cabalists is the same as that of the philosophers, the only difference being in the language employed (ib. III., iv.). Still in halakic matters he decided against the Zohar ("Darke Mosheh" on Ṭur Oraḥ Ḥayyim, 207; ib. on Ṭur Yoreh De'ah, 65). Gemaṭria

Crudely translated this means something like:

[Isserles] wrote a kind of philosophical writing, a symbolization of the temple, the temple rituals and the devices, which, just as tasteless and stupid as it seems to us, so was it suited to the taste of time, and the scholarly Azariah dei' Rossi really liked it.

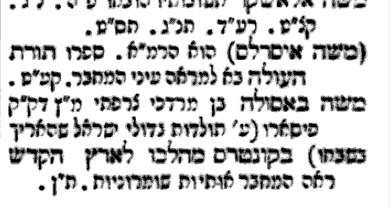

Recognizing the limitations of my translation, here is it how it appears in Hebrew (Rabbinowitz, V. 6), where you can clearly see that he is claiming that Azariah dei' Rossi approved of the תורת העולה:

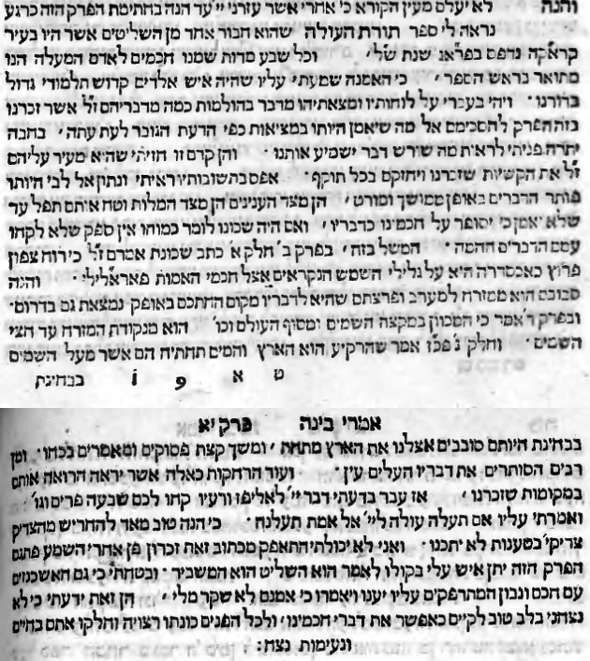

How magnanimous and culturally relativistic of him! Be that as it may, it's remarkable that he writes that the educated Azariah dei' Rossi "sehr gefallen hat," because a substantial part of Chapter 11. of Section 2 (Imre Binah) of dei' Rossi's Meor Enayim is devoted to not exactly admiring תורת העולה.

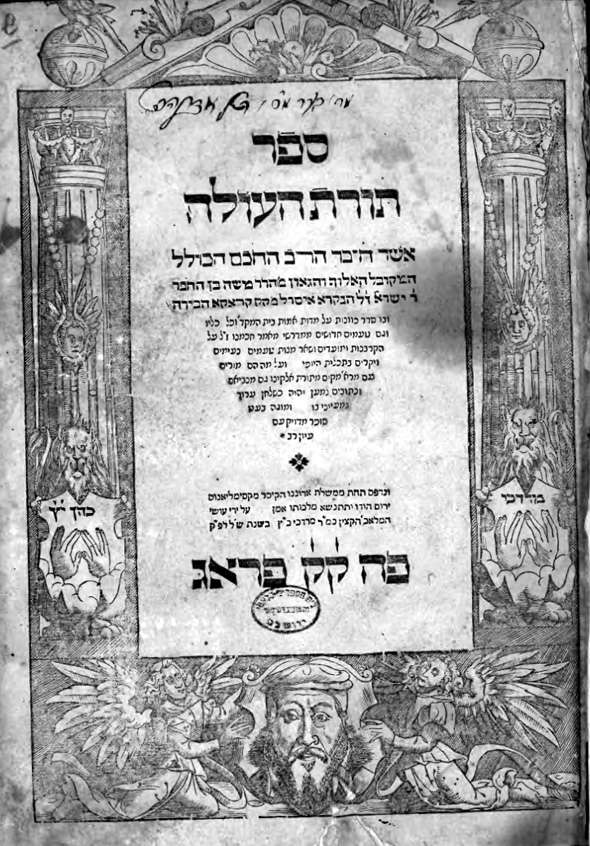

Incidentally, this is the title page of the 1570 edition which dei' Rossi himself will discuss (below):

Wouldn't it be fun if today's seforim had gargoyle's on the title page too? but I digress.

Here's what dei' Rossi writes:

Dei' Rossi begins by noting the very extravagant praises of the Rema given on the title page, seven titles (pictured above). It is clear that he knows very little about him firsthand , for he writes that he has been told that he is a godly man, holy, and one of the greatest Talmud scholars of our generation (the Rema was a younger contemporary; according to Google maps it would take 11 hours and 49 minutes to drive today from Krakow to Ferrara. How much more was the distance 500 years ago). From skimming the table of contents, he saw that the Rema discusses some of the statements of Chazal, things that were discussed in this very chapter , to show how they were consistent with the views of our time. He noticed that the Rema raised the same questions that he had, and even reinforced them. Thus, dei' Rossi seems to have anticipated something special, especially in light of the Rema's reputation. Instead, he discovered that the Rema interpreted them in what he felt is a farfetched way which is inconsistent with the language of these statements of Chazal. Examples are supplied. He ends by suggesting that the Rema would have been better off if he had remained silent, rather than trying to justify the righteous (Chazal) with incorrect arguments. Why did he feel it necessary to include this piece? In anticipation of someone bringing the words of this Shalit (ie, the Rema, in Torah ha-Olah) to his attention; so now he shows that he's already seen it and here's why he rejects it. Finally, he writes that he trusts that the Ashkenazim, a wise and understanding people, who are attached to the Rema, would agree that what he's written is not incorrect. "This I know, that although he is good-hearted in his attempt to uphold the words of Chazal, he hasn't disproved me. In any event, his intention was worthy and his portion is in the pleasant eternal."

That's pretty wild, huh? Not exactly what Graetz had in mind.

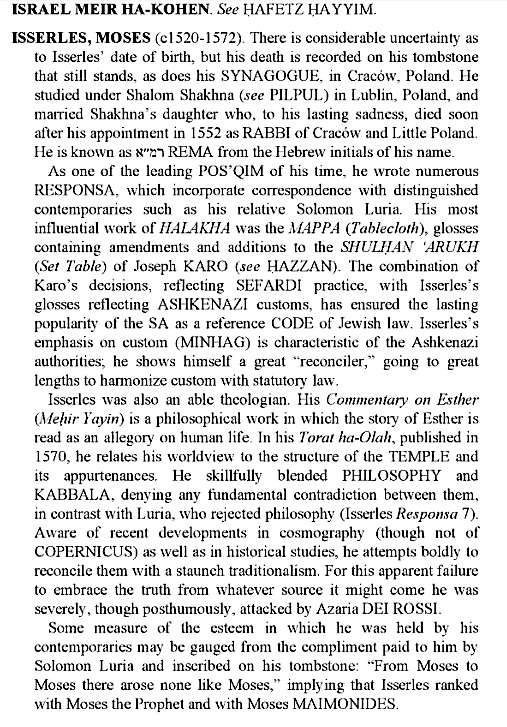

This attack is apparently so famous that it made it into a small description of the Rema in a popular work, Historical dictionary of Judaism by Norman Solomon.

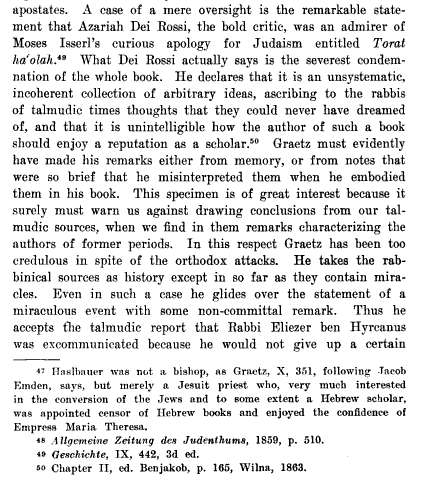

Why did Graetz write that? If one examines the edition of Meor Enayim he likely used, that is the latest, best edition printed a number of times in Vilna in the1860s by the holy printing press the house of Romm, which somehow printed the Meor Enayim (link) one sees what is written in the entry for the Rema in the very helpful index of sources provided by Benjacob:

Indeed, if one looked up the Rema in the index and then didn't take a look at what was written therein on pg. 179 one might conclude, as Graetz did, that Azariah dei' Rossi was a fan of תורת העולה!

Now, all this isn't my discovery. Writing a tribute to Graetz on the centennial of his birth in 1917, Gotthard Deutsch had the following to say:

As you can see, Deutsch concludes that Graetz must have misremembered or misunderstood his notes. This is understandable, as the 1863 edition of Meor Enayim doesn't include an index. Only when it was reprinted in '64 and '66 was the index included. Since Graetz doesn't indicate that he used any modern edition (but I think it's safe to say that he did use the Vilna edition) I assume that he hadn't used the '63, but the '64 one. Therefore I conclude that he got his information from the index of sources which he badly misconstrued. This doesn't mean that he never read Ch. 11 (or Toras ha-Olah) at all, but it does seem like the extent of the legwork he did for this line in his monumental history was to incorporate a few words in an index. This is how, it seems to me, such an erroneous statement made it into print, and was reprinted many times, apparently without correction. In fact, the Hebrew translation (pictured above) often includes valuable notes and enlargements, but here - nothing.