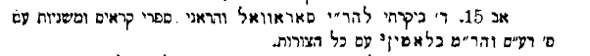

"I visited Rabbi Jacob Raphael Saraval and he showed me books of the Karaites and Mishnayos with the commentaries of Bertinoro and Maimonides in Latin, with all their illustrations."

For some reason this interested the Chida. אין משיבין על המעשה. Recently all six volumes of this magnificent and interesting edition of the Mishnah became available digitally (link). I thought it would be interesting to discuss this edition, but first a little about the aforementioned Rabbi Jacob Raphael Saraval of Venice and Mantua (1708-1782).

Rabbi Saraval, a pupil of the famed Rabbi Yitzchak Lampronti (author of the rabbinical encyclopedia Pachad Yitzchak) was an erudite scholar, translator, poet and apologist. The meeting described above occurred in 1775, but the Chida must have met him as early as 1754, where he describes a eulogy he heard him deliver which must have been quite exhausting:

"During that week [2 Shevat 5514] Rabbi Jacob Saraval delivered a eulogy for the aforementioned Rabbi Gur [Aryeh Finzi] for three hours, in the vernacular; rhetorical and elevated speech."

Getting back to 1775, two weeks earlier (26 Tammuz) the Chida describes an earlier meeting at Rabbi Saraval's home, where he was shown a bible printed in Constantinople in 1505, important because it was printed by exiles from Spain. The Chida writes that it contained "new haftarahs (הפטרות חדשות)" whatever that's supposed to mean. On Tisha B'Av Rabbi Saraval mentioned the Chida from the pulpit in an honorable way (the Chida never fails to note when he was shown respect or its opposite; what can I say, he was human). He seems to have appreciated the nice words the Chida said about the community of Mantua, although he told his congregation that he's appreciate it if they'd learn to conduct themselves in holiness after the manner of Rabbi Menachem Azariah of Fano and Rabbi Moseh Zacut (a Mantuan rabbi who died in 1697).

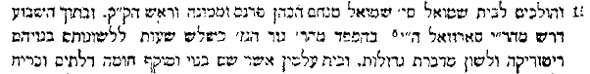

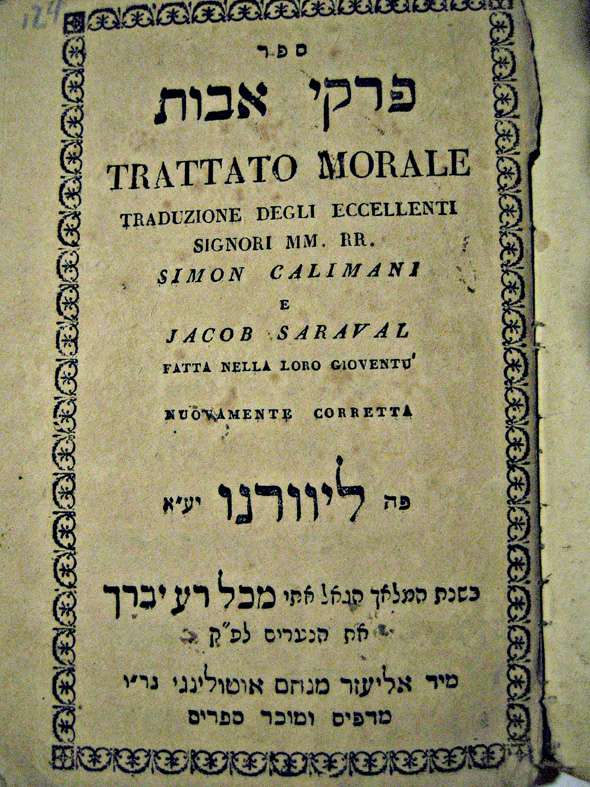

In his youth, Rabbi Saraval collaborated with a fellow pupil of R. Lampronti, Rabbi Simcha Calimani on an Italian translation of Mishnah Avos (1729). Also of some interest is that Rabbi Saraval had a relationship with Benjamin Kennicott and evidently exchanged correspondence (perhaps they even met, as Saraval spent some time in England). He seems to have supplied Kennicott with at least two Hebrew Bible codices for his collation and you can read a little snippet of a quote from Saraval in his Dissertatio Generalis (1783) on the text of the Hebrew Bible (pp.508-09). Although my Latin is poor, (okay, almost non-existent) Kennicott quotes Saraval: "Varietatem lectionis, in msto magno numero reperiendam, ex consensu sum antiquis verzionibus diiudicandam esse" which means something like "Textual variants must be compared with the ancient Jewish versions" [Targums and the like].

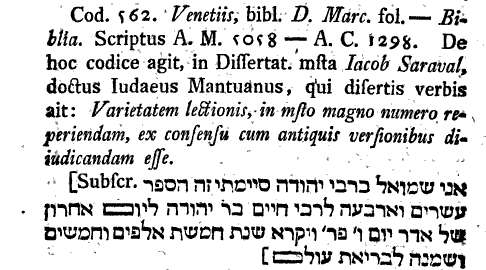

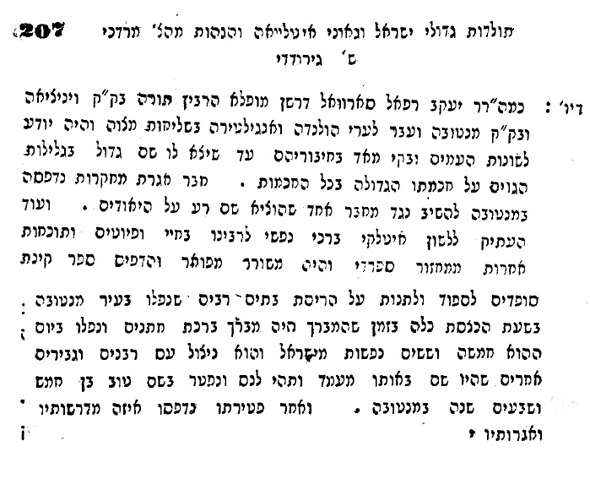

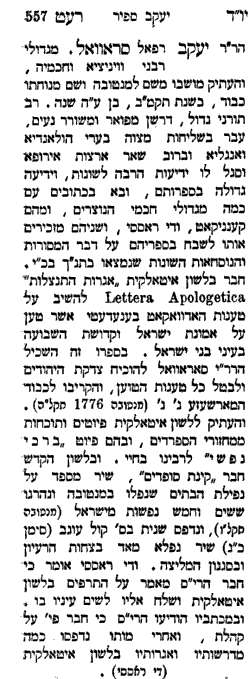

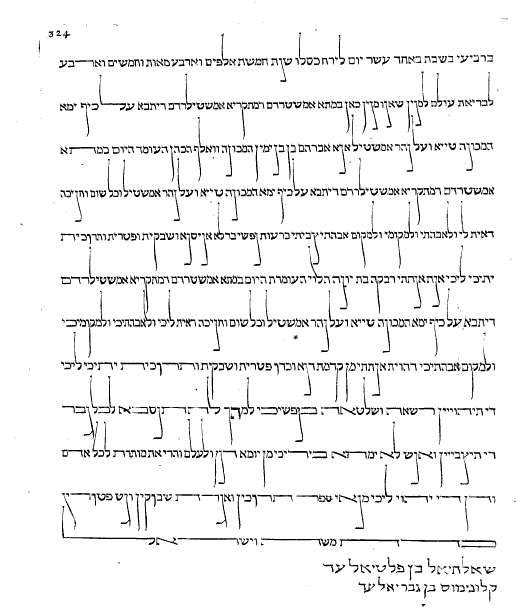

Here are two biographical entries about him:

Rabbi Marco Ghirondi's Toldos Gedolei Yisrael should come first as it is probably a source for the second one:

Shmuel Yoseph Fuenn's Knesset Yisrael:

You can read some of his Hebrew poetry here in Shirman's anthology of Italian Hebrew poetry.

ETA 4.13.10:

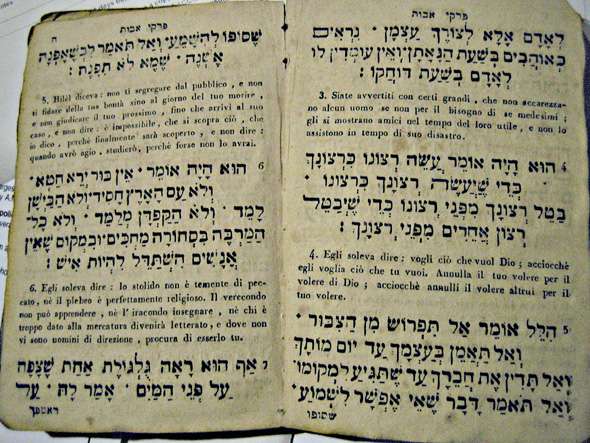

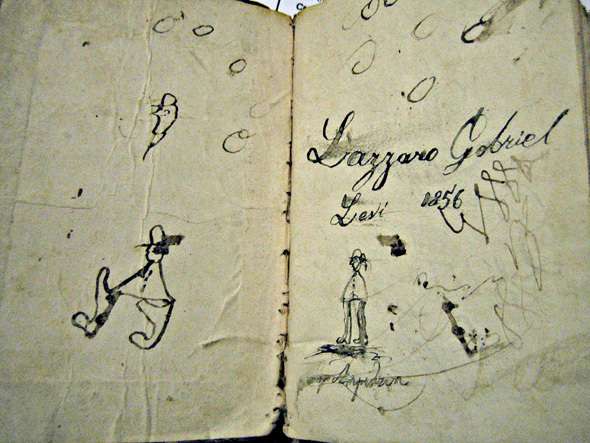

Many thanks to my friend Dan Klein for sending me the following photographs of the 1732 Livorno edition of the Calimani/ Saraval translation of Pirkei Avos, which is a family heirloom:

Dan, who's knows Italian very well, pointed out to me that it is strange that on the title page we are told that they translated it "fatto nella loro gioventu" which means "done in their youth." Since in 1732, which was only three years after the initial publication, our authors were all of 25 years old or so it seems strange to speak of their youth this way. Although it is possible that it's just strange language and they were still in their youth, my reply to Dan was that it's possible they could have done it when they were 13 or 14, which would make sense of "in their youth," even though we are accustomed to thinking of 22 year olds as youths. Translation seems to have been a big aspect of Hebrew study in Italy, so it would make sense as a very youthful exercise. In addition, this was still the era before delayed adulthood, even recognizing that 21-22 could also have been considered "youths" back then. But remember, the Ramchal was a seasoned author and teacher by his early 20s, and they were roughly the same age.

* * *

If someone is still reading, it's time for the Surenhuys Mishnah. Willem Surenhuys (1664-1729) was a Dutch Hebraist who made a major contribution to Christian Hebrew studies in producing an exceptional work, the 63 tractates of the Mishnah in Latin, along with the commentaries of Rabbi Ovadiah Bertinoro and the Rambam, and their introductions. To put that into perspective, with so much contemporary Jewish translation projects, has anyone even imagined not only translating the Mishnah, appending useful notes, but also translating the perushim of the Bertinoro and the Rambam, not to mention an impressive Hebrew index? No small achievement. The truth is that many tractates already existed in Latin translation. In fact Surenhuys used the existing translation of 26 of the 63 tractates, which itself is interesting; that is, to know that before 1698 26 tractates of the Mishnah were already translated into Latin.

While most Christian scholars of Hebrew had an interest in knowing what was in the rabbinic writings, Surenhuys (and those who followed him, such as William Wotton of England who translated Massekhtos Shabbos and Eruvin into English) had a particular interest in the Mishnah. His fervent belief was that the Mishnah is special, because it records the true traditions of the Jews! While most Christian Hebraists doubted, to put it mildly, that there was any credibility to the Jewish claim to possess a true oral Torah, Surenhuys did not see why this was not possible. He knew that the Mishnah was only a little later than the time of Jesus, thus it was probably a fair description of Judaism in the time of Jesus. Why shouldn't the Mishnah reliably describe, for example, Temple practice? This in turn sheds much light on the Bible. In addition, why shouldn't the Mishnah shed an enormous amount of light on the Judaism of the 1st century, when Jesus lived? For example, the order on marriage and related laws, Nashim, should be a treasure trove of information on authentic Jewish marriage practice, which could explain a great deal about the Gospels (eg, Jewish betrothal was relevant to the relationship between Joseph and Mary). But his interest was not purely scholarly. He also believed that the Mishnah could serve as a common link between Jews and Christians, since the Mishnah could be used to show the fulfillment of the Old Testament in the New.

Below follows an explanation of how Surenhuys came to this opinion, and then a review of this edition of the Mishnah from 1722, by Michel de la Roche (1680-1742) a French Huguenot who settled in England, and was the author of the series Memoirs of Literature, in which he presented the scholarly literature of the day that he had read to the public. Roche was very interested in and sympathetic to the ideas propounded by Surenhuys:

The review:

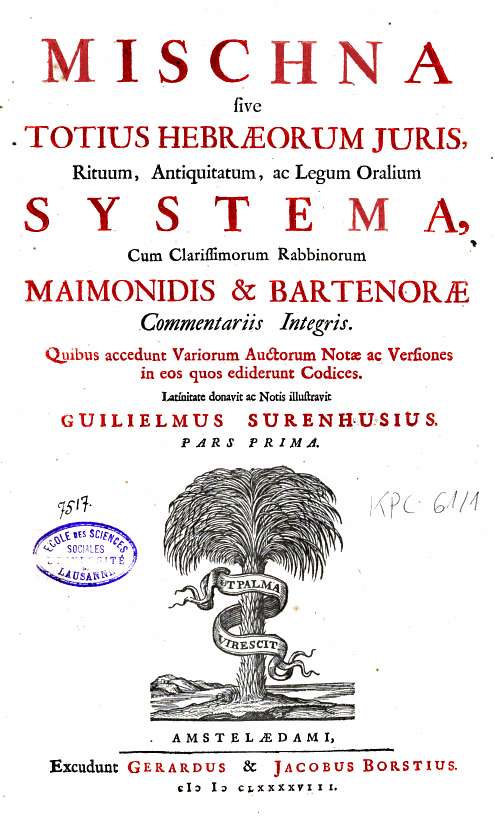

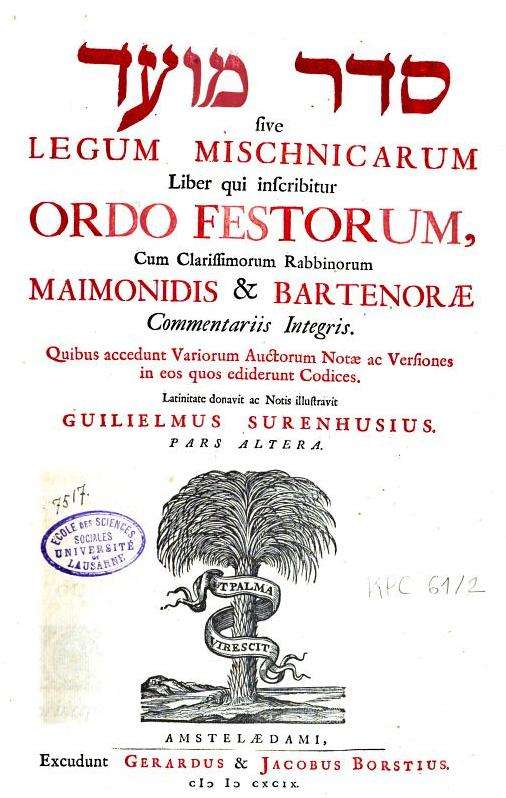

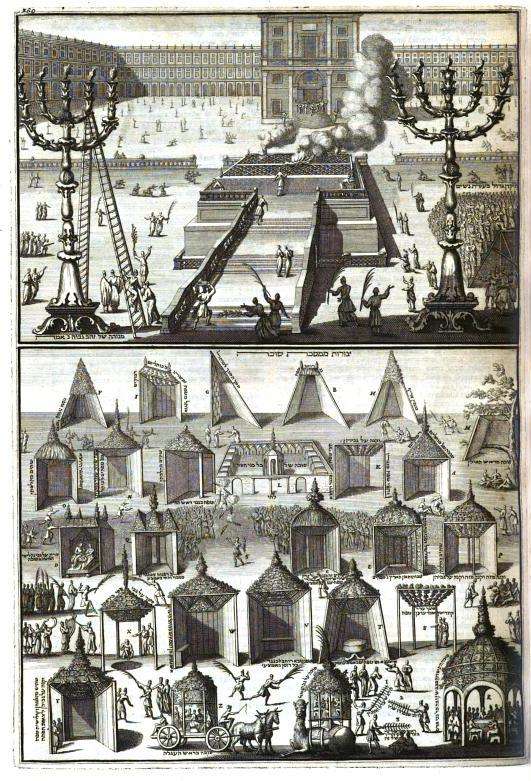

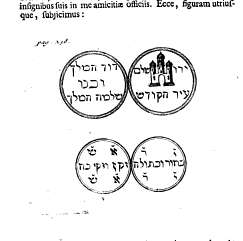

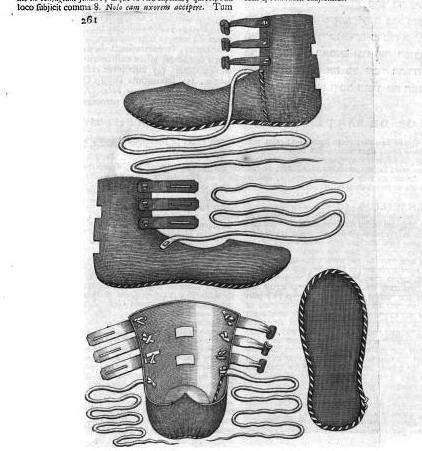

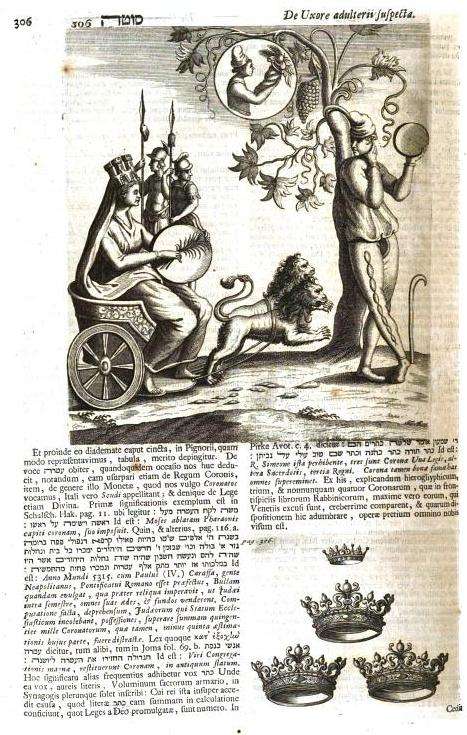

On to the edition itself. I will post the title page of two volume, a sample of what it looks like inside and then some of the interesting illustrations (which the Chida refers to) found throughout.

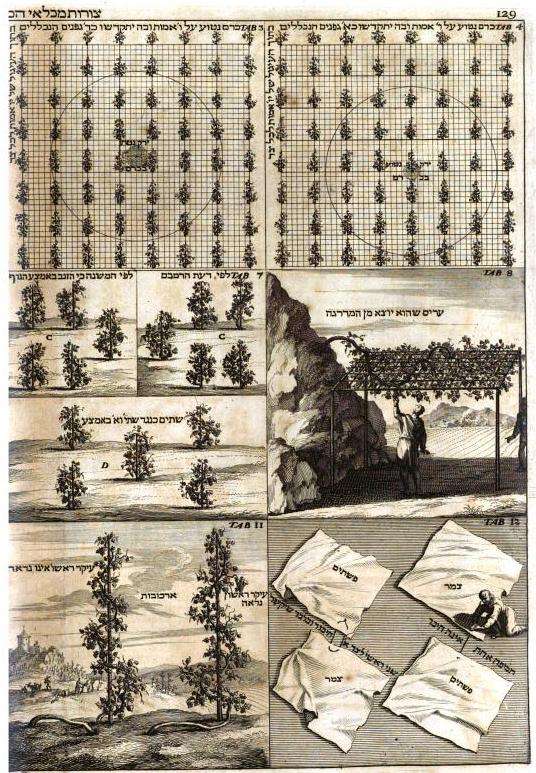

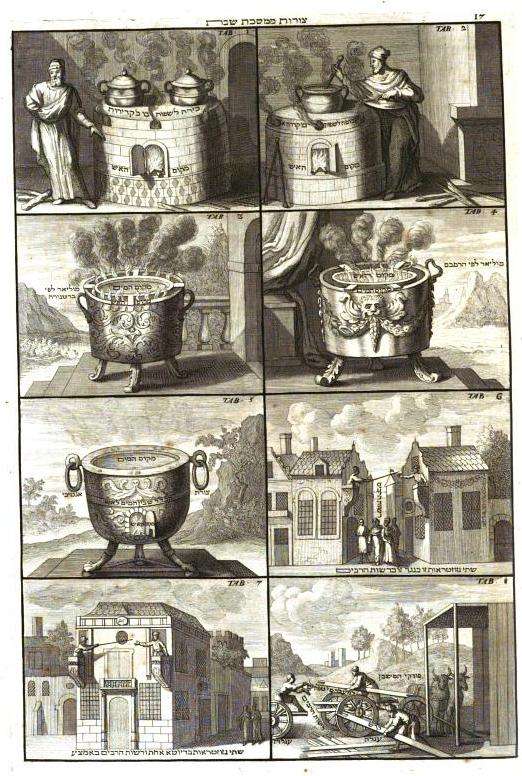

Note: these illustrations are only in the first three volumes, and were created and supplied by Jews, who had warmly supported the project. They are thanked and recognized in the introduction. This is especially interesting because, for example, when you look at the illustrations of sukkot you are looking at sukkot as known and imagined by actual late 17th century Jews. The reason why the later volumes lack illustrations is due to the death of Rabbi Isaac Coenraads of the German Synagogue in Amsterdam, who had been mainly responsible for supplying them.

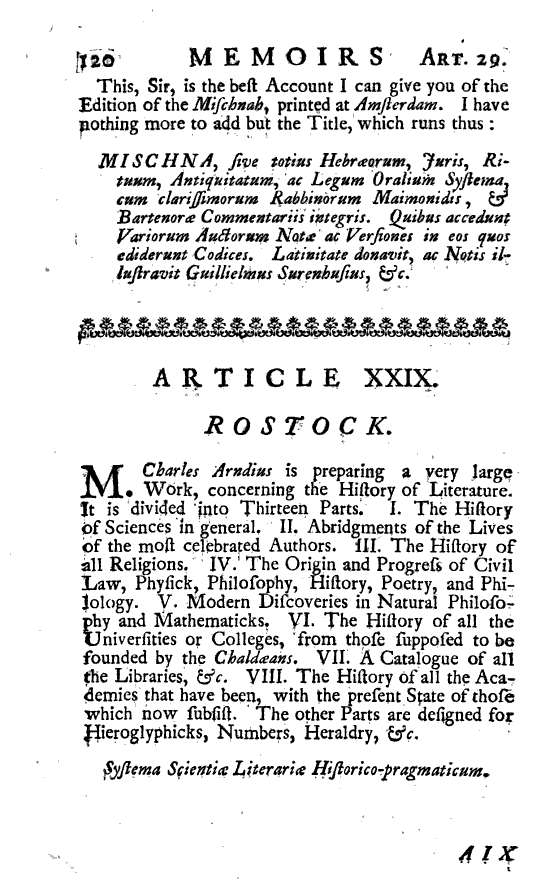

Title page:

Fairly typical pages from Vol. I:

Illustrations from Vol. I:

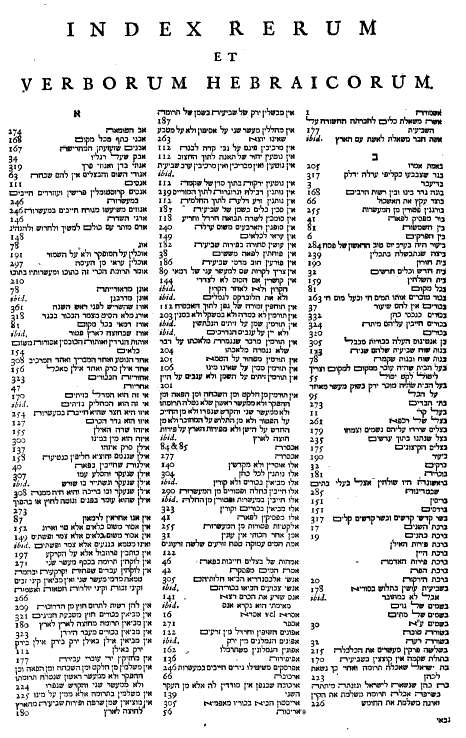

The impressive index:

Illustrations from Vol. II:

Title page. Only in the second volume is the Hebrew title given:

Illustrations from Vol. III:

Although the introduction to the 6th and final volume ended with a prayer hoping that his translation may help lead the Jews to Jesus, he is in the judgment of Peter van Rooden "quite probably . . . the most philosemitic Christian Hebraist of the seventeeth century." As Rooden points out, unlike basically all other Hebraists, he wished to keep theological polemics against Judaism separate from rabbinic scholarship. He himself never engaged in polemics, and took other scholars to task for their use of rabbinic literature to combat Judaism, which they only possessed because of Jewish teachers. The first volume is dedicated to the Burgomasters of Amsterdam, and he specially cites their humane treatment of the Jews as a reason for their deserving praise. In addition, throughout the translation and commentary he depends and relies upon the Jewish interpretation of the Mishnah, aided by Maimonides and Bertinoro. He avoids historical and theological criticism; he tries, in a word, to present the Mishnah as it is.

A final note: this is not really the first complete Mishnah translation. A Jew, Isaac Abendena, brother to the Haham of London at the time, translated the entire Mishnah into Latin, but it remained in manuscript in Cambridge University (Surenhuys had access to it and made use of it). Supposedly his brother had first translated the Mishnah into Spanish, but we'll leave that for another post.