There's a good chance that you've heard that the vulgar expression "to daven" (to pray) is derived from the Aramaic word for "of the fathers," the point being that Talmudic tradition ascribed the three daily prayers to the Patriarchs.

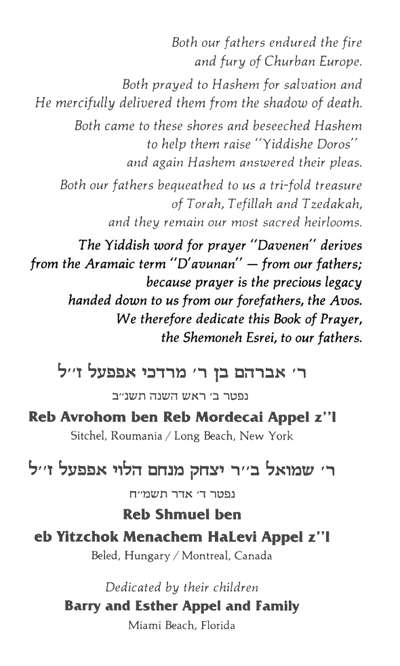

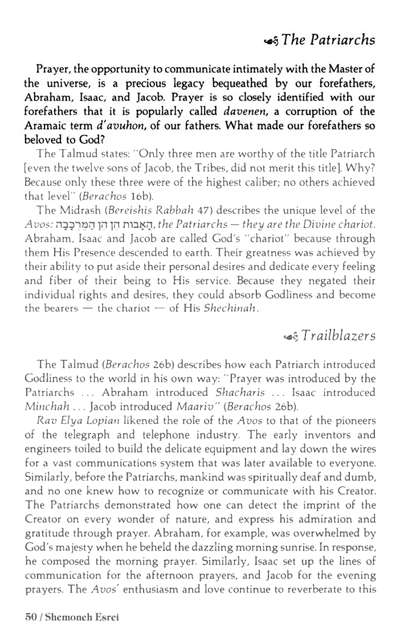

Here are two pages in Artscroll's Shemoneh Esrei - Inspirational expositions and interpretations of the weekday Shemoneh Esrei by Rabbi Avrohom Chaim Feuer.

As you can see, the first page is a dedication, presumably composed by the donors. It says "The Yiddish word for prayer "Davenen" derives from the Aramaic term "D'avunan" - from our fathers," while on page 50 the author writes that "Prayer is so closely identified with our forefathers that it is popularly called davenen, a corruption of the Aramaic terms d'avuhon, of our fathers." Thus, in the same book we have the suggestion that "davenen" (or "davening," as English speakers now call it) comes from דאבונן or דאבוהון. Neither comes with a source (although you might expect one from the body of the book rather than the dedication) although in my humble opinion the dedication people at least picked the form of the Aramaic word that sounds a whole lot more like davenen and makes a little more sense linguistically ("our father" versus "their fathers").

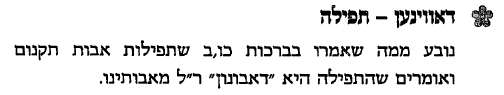

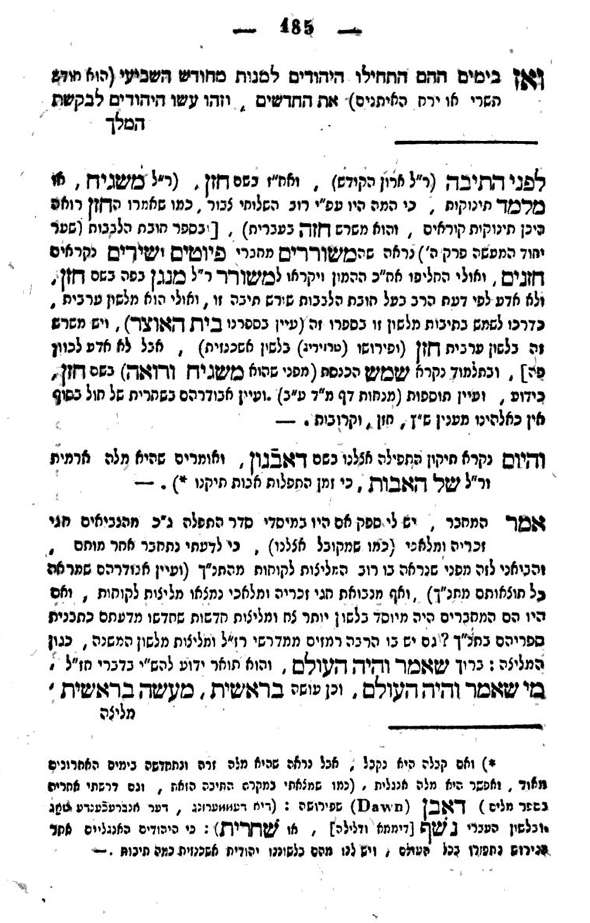

In Rabbi Dovid Cohen's exceedingly interesting and exceedingly unusual work Safah Yiddish Ha-kedosha ("The Holy Yiddish Language") we find the following:

Thus, Rabbi Cohen agrees with the dedication, דאבונן over דאבוהון, although he helpfully changes it to the plural, to make it come from "our fathers." It's unfortunate that he spelled it with YIVO Yiddish though, since it glaringly highlights how unlikely such an etymology really is - at least if it's spelled like that.

The truth is though that, fortunately for this etymology, in the early sources it is not spelled with all the Yiddish double vavs and ayins. It is indeed ב-based, if I may coin such a term. There's no need for me to give those sources. Are they not written in in Judah A. Joffe's 1959 article The Etymology of "Davenen" and "Katoves"? (PAAJR v.28)

Naturally the first place to look for such a word is in early Yiddish lexicons, or since it's from Aramaic, surely the Tishbite Elijah Bachur (whose 462nd jahrzeit was very recently) would mention it in one of his books, even if only to make fun of it. However, no such thing occurs. Joffe gives two early sources ("earliest so far known to us," speaking in 1959) , one from 1595 and one from a book written by a woman who died in 1550, but first printed in 1609. I don't know what crafty scholars of this word have dug up since, but I am sure a whole crop of 13th century "davenens" have not. So let us assume that it begins to appear in the 1500s. In these early sources the word is spelled דבנין. But of course there was no such thing as an official way to spell Yiddish words, and therefore a source from 1695 spelled it דאוונן.

In any case, my opinion is that it is difficult to imagine how a word corrupted from Aramaic actually arose so late. Who would have thought to term prayer "דאבונן" in the first place? And there's no trace of it, except for the appearance of the term already corrupted? Unlikely, I think.

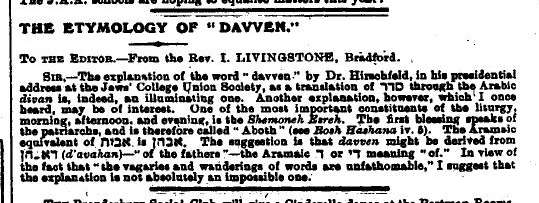

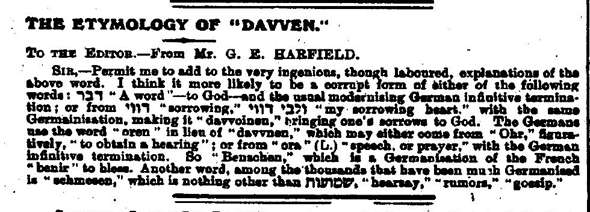

This theory did not pop up in Brooklyn. As you can see, it was discussed in the letters section of the Jewish Chronicle in March of 1913:

Of course no one really knows its origin, and anyone who tells you otherwise is just picking their pet theory, and there have been many, none really more plausible than the Aramaic theory. Here's another one from two weeks later:

One which I love - although it is obviously wrong - appears in Yitzchak Baer Levinsohn's book Beis Yehuda (oh, how I would have loved this book when I was a yeshiva bochur. One can only imagine how exciting it was to read this book 170 years ago when it appeared).

Free translation:

Nowadays the fixed prayers are called by us דאבנון (he, in Russia, is well aware that in Central and Western Europe it is still called "Oren," not "Daven"). They say that this word is Aramaic, meaning "of the fathers," since the times of prayer were established by the Patriarchs.

Then he footnotes:

If this is a correct tradition, then we will accept it. But it seems to me that this is a strange word, coined only relatively recently. It is possible that it's an English word (for which I find support in how it's pronounced, as I expound in my lexicon) דאבן (Dawn), which means (the dämmerung, the breaking of the day, or in Hebrew נשף [of the day and night], or שחרית) : for after the expulsion, the English Jews dispersed all over Europe, and we received many words from them in our language, Judeo-German.

Unfortunately Levinsohn did not say who "they" are who say it's Aramaic, and I couldn't find anyone prior to him who was saying it. Maybe it was said orally, or maybe I just didn't find it.

But regarding his theory, of course I recognize the weaknesses, not the least of which is that creating a term from "to dawn" is not even slightly more plausible than "of our fathers." But I love this one because - well, readers of this blog can probably guess why. Yet Joffe felt it was so bad ("sheer nonsense") that he apparently did not even want to name the one who proposed it. Joffe pointed out that "the older form was related to dagan, daybreak. The proponent did not know that the "w" was silent."

I feel that this needs further explanation. A source that I find to be relatively accurate, and certainly an excellent point of departure, is the Online Etymology Dictionary, which is compiled by Douglas Harper, who writes that he is not a linguist, but "compiler of the works of the professionals in the discipline." This is indeed the case. What you will see in this OED is sound information, insofar as it is all derived from competent scholarly sources.

So the entry for dawn (v.) reads

late 15c., shortened or back-formed from dawning, dawing (c.1300), from O.E. dagung, from dagian "to become day," from root of dæg "day" (see day). Probably influenced by a Scandinavian word (cf. Dan. dagning, O.N. dagan "a dawning," Ger. tagen "to dawn"). Related: Dawned; dawning. The noun is first recorded 1590s.

The Jews were expelled from England in 1290. They obviously didn't bring a word which didn't exist until centuries later with them. Here is a good place to mention the g/ w interchange, which is not some kind of secret route to avoid traffic on the George Washingston Bridge. I don't doubt that many have wondered why the city of Worms appears as "Vormayza" (וורמיזא) and "Gormayza" (גרמיזא) in Hebrew sources. The answer is really rather simple, and it's the same reason why the name William is Guillaume in French, or a French-derived English word like warranty is garantie in French. The W and G switch in these languages. Worms is the German Jewish pronunciation, and Gorms is the French. This may - or may not - also serve as incidental proof that medieval Jews pronounced the ו like the English /w/, but I'm not betting on that one. In case one wonders where that -ייזא suffix came from, the medieval Latin name for the city was Vormatia.

Thus, we see the consonant switching properties of /g/ and /w/ and evidently some such process brought about "dawning" from the Old English "dagung," which in turn produced "dawn," but only much too late.

As for the matter of whether Levinsohn did or did not "know that the "w" was silent," I must come to his defense and suggest that Levinsohn surely knew that in 1839 the "w" was silent. Why should he have assumed it was silent many centuries earlier? On the contrary, a basic rule of thumb in English is that although the written language is full of silent letters today, they were almost all pronounced at some point. Indeed, no one was so stupid as to compose such ridiculous spellings, as people often assume was the case in English. The pronunciation of words changed faster than the spellings, and by the time anyone paid attention enough to try to change the spellings to conform with the pronunciation, it was too late and no one was interested in spelling reform.

Ultimately Joffe proposes something that to my mind is most likely correct, although the fanciful scenarios he proposed to set the tone for it are a little over the top. Go to Google Translate enter the word gift, translate the word to Latvian or Lithuanian and out pops "dāvana" or "dovana" which one can plainly see sounds a whole lot like "daven." Since one of the prayers happens to mean "gift" (or "offering") in Hebrew, namely the afternoon prayer מנחה, one can hardly ignore this. Since Joffe knew that to just say it raises questions, he tried to establish common scenarios where Jews engaged in business transactions prayed while gentile visitors were in their home or place of business. His theory is that they would excuse themselves, using the term "davana" by way of explanation. "Pardon me, I'm going to excuse myself for my afternoon 'offering." He does indeed show a couple of instances in literature, but I hardly think that's necessary.

To come full circle, while this one seems convincing to me, אם קבלה היא נקבל.

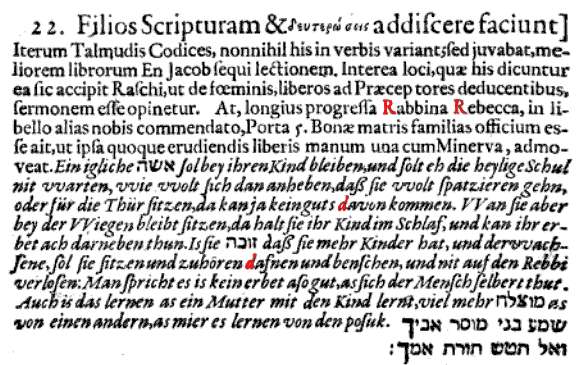

Incidentally, the aforementioned woman whose book (מנקת רבקה) was first published in 1609 is Rivka of Tiktin. Wagenseil refers to her and quotes from her book (Sota pg. 420). As you can see, he calls this learned woman Rabbina Rebeca, Rabbi Rebecca:

Readers interested in the other etymologies that have been proposed should read Joffe's article, as well Balashon's post. Hartwig Hirschfeld, who was a big Arabic scholar felt it came from "diwan," and seemingly everyone picks the one that - shockingly - is closest to their field. Thus it is hardly surprising that Masseches Berachos 26b should be source of what seems to be the official Orthdox etymology (even if no two people can agree on the precise Aramaic form).

I'm sure the latest Yiddish scholarship has made it to be the Khazar word for drink a l'khaym or something, but they can keep it.