This page is from Abigail Lindo's (1803-1848) Hebrew and English and English and Hebrew dictionary: with roots and abbreviations, which was very modestly "Not Published" in London in 1846, according to the title page, in which she also names herself Abigail third daughter of David Abarbanel Lindo, Esq., much as any pious author does (give the greater honor to their father than to their own name). This is, in fact, the third, twice enlarged edition of her book, which was first printed in 1837.

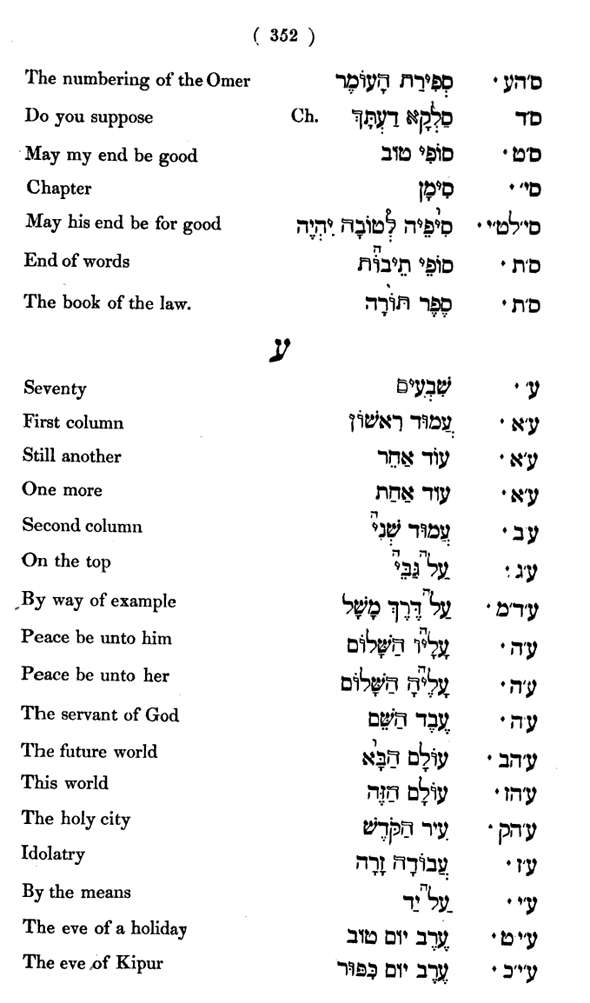

As you can see, detail below, she employed the very same technique used by Elias Hutter in his Bible "that can teach you Hebrew," as I called it here. That is, he used a hollow font to differentiate between the stems and roots of Hebrew words with the result that the reader could automatically know a great deal about the construction of each word as they read it. As she puts it in the introduction, "The hollow letters indicate the serviles, the others form the root; whilst the small letters placed over a word must be added to complete the root." Compare:

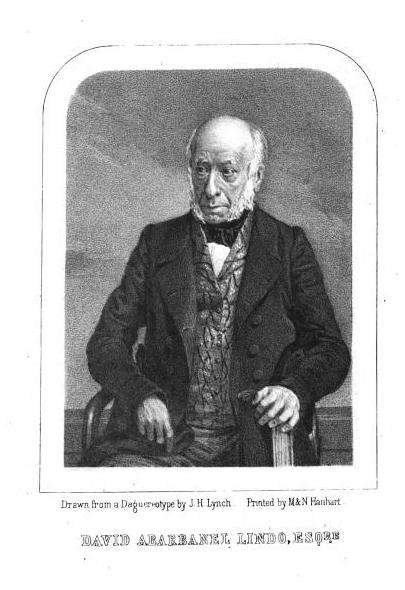

For some strange reason this only appears in her section on abbreviations, rather than in the dictionary proper. My guess is . . . cost? She does not say. In the intro she further thanks her "revered father," as well as the Haham Rev. Dr. D. Melodla, who gave her information for which she is grateful. The book (not published, mind you) is dedicated to her cousin Sir Moses Montefiore, and includes an engraving of her father, looking positively Dickensian (and I don't mean a Dickensian Jew ala Fagin).

David Abarbanel Lindo (1765-1851) was a mohel, and he performed the bris milah on his nephew Benjamin Disraeli in 1804 (born D'Israeli and, well, an Israelite). As Lucien Wolf elegantly put it, "It was David Abarbanel Lindo who performed on Lord Beaconsfield the ceremony of initiation into the Covenant of Abraham"

In his daughter's dictionary proper, there is a wonderful technique, which is to place the roots of each word in a clear and sensible way right next to each entry. Here's a representative example - representative not only of the technique, but also her many compound word neologisms, included no doubt so that the student can learn to make Hebrew a contemporary, flexible language:

In a similar vain, the better-known and more forthright young English Jewish authoress Grace Aguilar wrote the following hopeful prediction, in 1845:

". . . if we can but establish in every land a vernacular Jewish press, it will work more and more. The grammatical study and acquirement of our own noble language, the Hebrew, which is now made part of the education of every Hebrew child, will forward this glorious end. The light is dawning over many lands, but a faint, faint streak indeed, but enough to promise, for God himself has said it, that it will "brighten more and more into the perfect day,"and permit "the Sun of [Righteousness" to rise and shine on all the nations, as the light of heaven on the earth. Ages may pass, indeed, ere this will be, but man has power of progression in himself, and Will attain it."

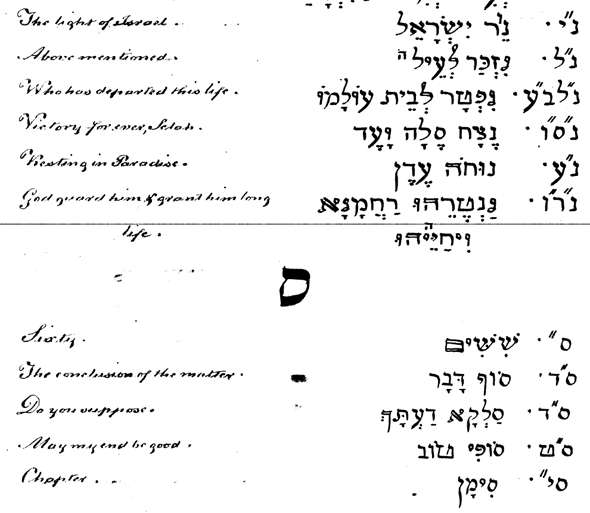

As it happens, a manuscript of this wonderful work is online, thanks to the JTS Library and hebrewbooks.org (via hebrewmanuscripts.org). I don't know if this is in her own hand or not. But as you can see, even in manuscript the method of hollow letters was used, so perhaps my earlier conjecture about cost of printing was premature. Maybe the intention was that it would be too distracting to be used throughout.

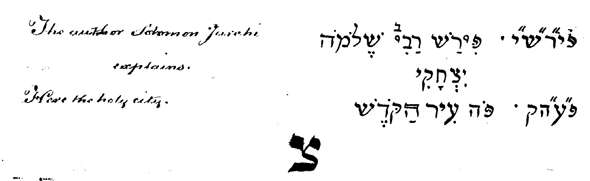

Someone should compare the book and the manuscript. I noticed that at least some of the material was nor printed. For example, the manuscript entry for the abbreviations beginning with the letter פ contains no less than two entries which did not make it into print, and I assume there are many more:

The first one - פירשי, or "the author Solomon Jarchi explains," is interesting because of how she vocalizes Rabbi Shlomo - רַבִּי שֶׁלֹמֹה - It uses the very un-Sephardic vocalization of רבי with a patach, which I think is more a tribute to 18th and 19th century Hebrew grammatical scholarship than the fact that Rashi was an Ashkenazi (yes, I know that's irrelevant historically for this vocalization). Next, she put a seghol rather than a sheva under the ש, which I tend to think is a minor mistake, influenced by her Sephardic pronunciation.