Okay, maybe not exactly.

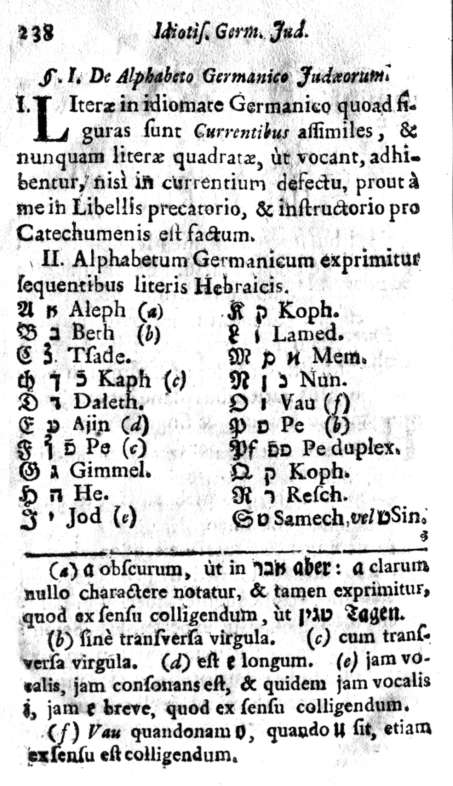

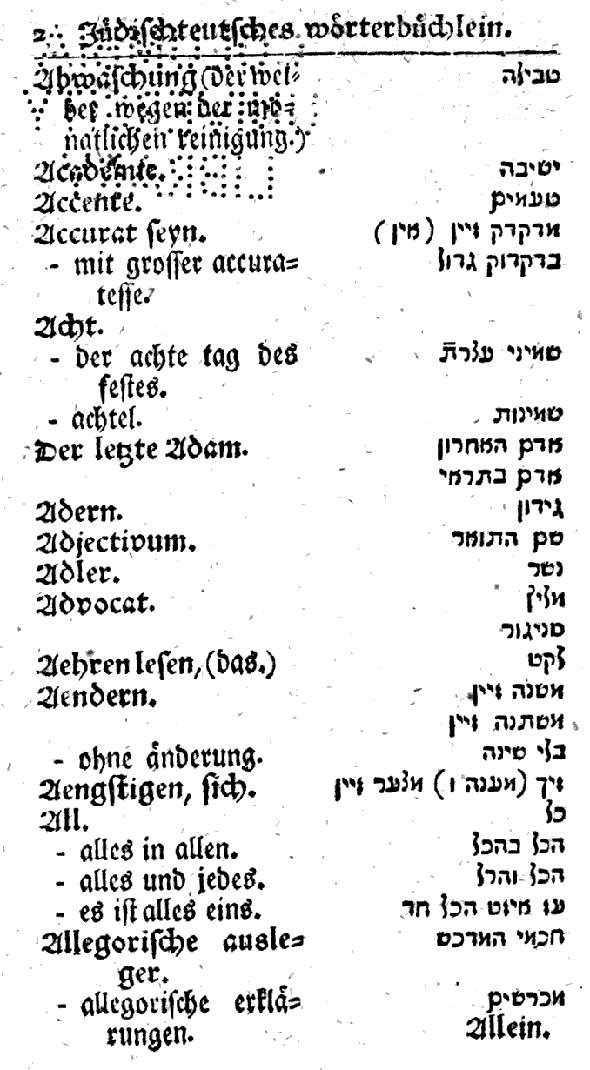

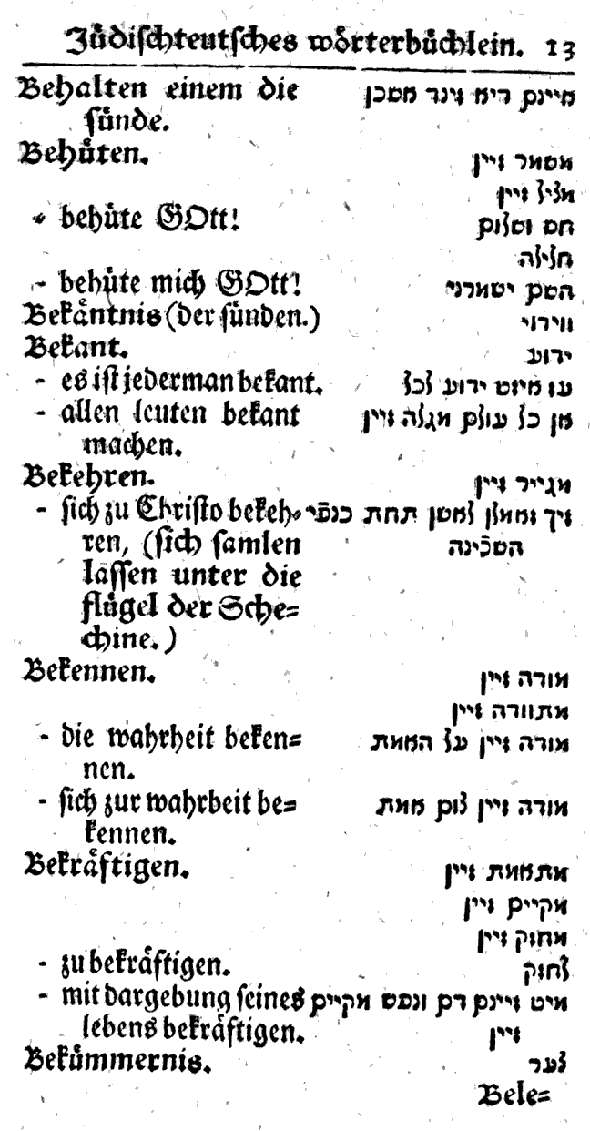

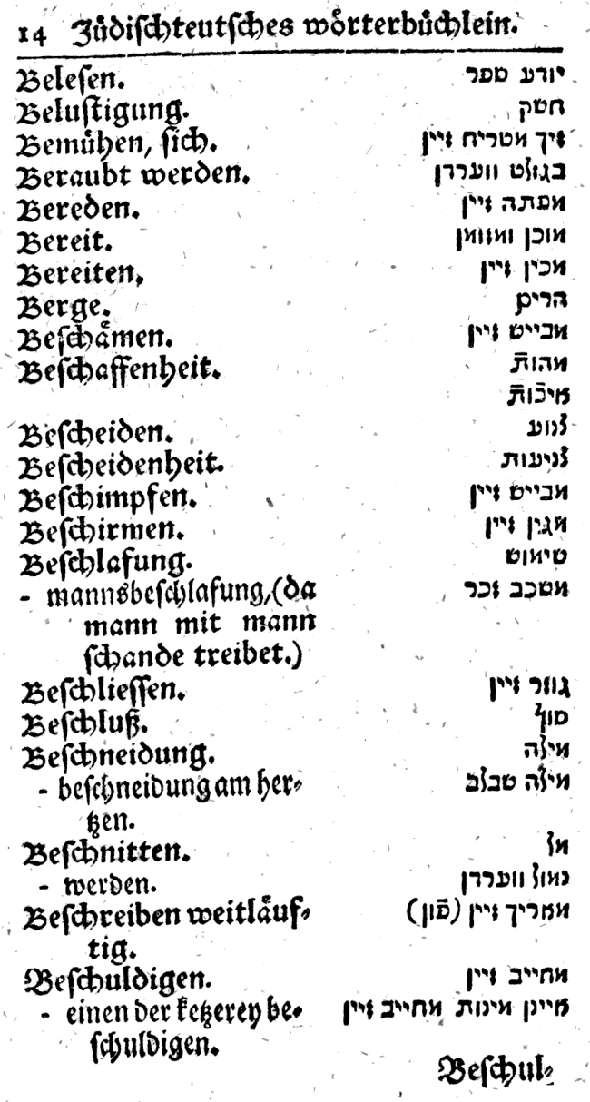

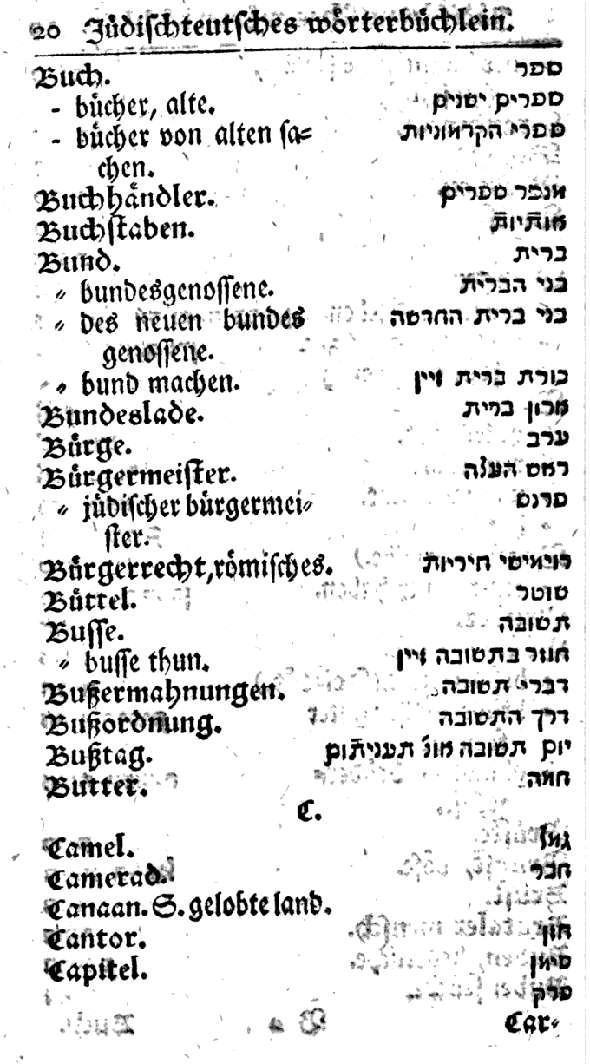

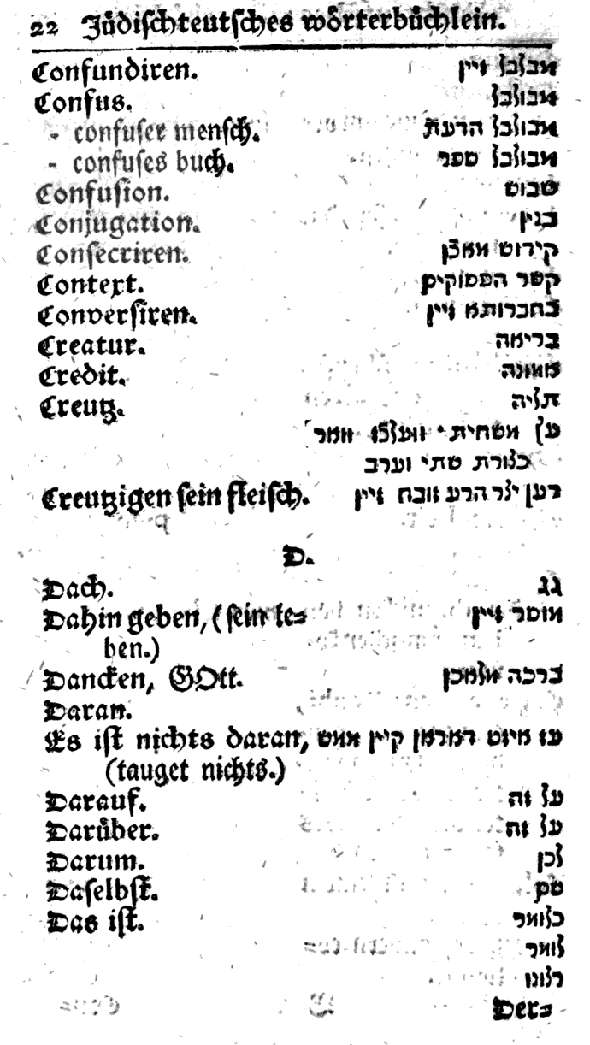

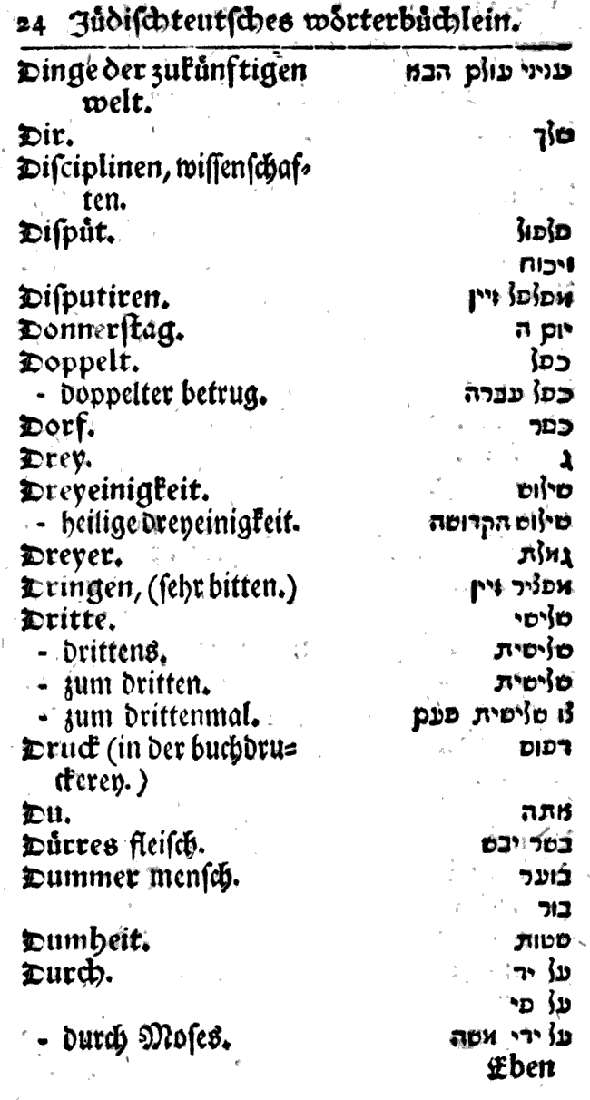

In 1736 Johann Heinrich Callenberg, an Orientalist heavily involved in missionary work, printed a dictionary called Jüdischteutsches Wörterbüchlein (Yiddish-Teitch Dictionary) which is basically a dictionary of the Jewish and Hebrew content of the Jew's dialect of German spoken at the time, which would not have been familiar to Christians. The words and phrases are arranged in alphabetical order, according to the German meaning. Thus, there is no theme or order on the Hebrew side. The purpose of this dictionary was to enable Christians to understand Jews when they spoke amongst themselves, to understand Jewish literature written in Yiddish, and to engage Jews in their own tongue. With 148 pages of entries and an average of 26 or so per page, the lexicon includes approximately 3900 words. Following the lexicon is an alphabetical index of the Hebrew words, and a short guide to the language, including pronunciation rules.

As you can see, the Hebrew text is printed using Wayberteitch, or the special Yiddish font which survived until well into the 19th century. Thus, the text presupposes that the reader not only has a basic reading knowledge of Hebrew but already knows how to read the Wayberteitch font - which anyone who is familiar with the Rabbinic or Rashi script can read with some practice.

As you can see, the Hebrew text is printed using Wayberteitch, or the special Yiddish font which survived until well into the 19th century. Thus, the text presupposes that the reader not only has a basic reading knowledge of Hebrew but already knows how to read the Wayberteitch font - which anyone who is familiar with the Rabbinic or Rashi script can read with some practice.

The rabbinic font was not widely known to Christians, and this one all the less so. Therefore this book is hardly for a novice Hebraist. Rather, it is for someone who had already been schooled in the Alphabeto Germanico Judaeorum, perhaps by reading a book like the following:

Samples: סתם which is translated as Absolute, מודה זיין על האמת, and צנוע and צניעות as well as שימוש and פסקן, and - oddly? - משכב זכר (da mann mit mann schande treibet). פרנס, which is translated as juedischer buergermeister, חוזר בתשובה זיין, which is proof that there were BTs 275 years ago (also mann mit mann schandes, but I digress). קשר הפסוקים is defined as "context," אמונה is "credit, מפלפל זיין is to Disputiren. Since, in the final analysis, this book is meant for missionary purposes, it also gives a Yiddish (actually, Hebrew) equivalent of the heilige dreyeinigskeit (holy trinity), שילוש הקדושה. In what I suppose is a cultural nod to the culinary realities of the unrefrigerated 18th century, there is also a term for dried meat, בשר יבש. These sample are from the first few pages, but there are - as I said - almost 4000 entries!

In truth it's worth looking over the whole book. In it, you will see an interesting lexicon of early 18th century Ashkenazic terminology - some no doubt assumed or invented, but much of it quite real.

See this post for an overview of a Hebrew version of Luke written as a rabbinic Bible commentary, and also published by Callenberg.