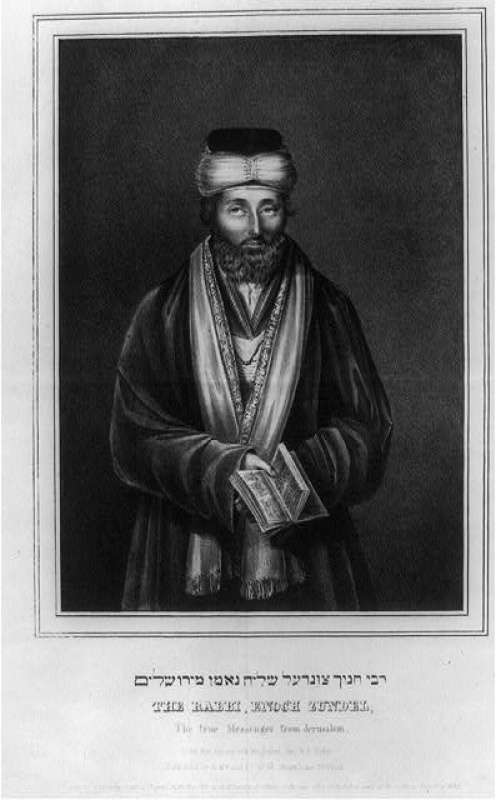

The caption reads רבי חנוך צונדעל שליח נאמן מירושלים / The Rabbi Enoch Zundel The True Messenger From Jerusalem. When he was here he helped establish a fund raising society called חברת תרומת הקודש (as they usually were) for the Jews of the Holy Land. Writing in 1849, Isaac Leeser recalled:

We well recollect the first occasion when the society was established: but if we mistake now, it owed its origin to the appeals of the learned Rabbi Enoch Zundel, who was sent to this country and Europe by the congregations of Palestine to plead in their behalf. His urbane manners, and elegant countenance, we are sure, cannot have been forgotten. He, at least, was a true and honest man. (The Occident VII No. 4, Tamuz 5609/ July 1849)

One of the people he made a profound impression on was William L. Roy, a Brooklyn-based Hebrew scholar. Roy was so taken by him that he took it upon himself to translate some Hebrew letters for the benefit of Christians, and in general he promoted Rabbi Chanoch Zundel as an exotic and profound person. In return, the rabbi seems to have written a testimonial or approbation for Roy's magnum opus A Complete Hebrew and English Critical and Pronouncing Dictionary which, as you will see, was justly criticized for being a less than impressive work of scholarship.

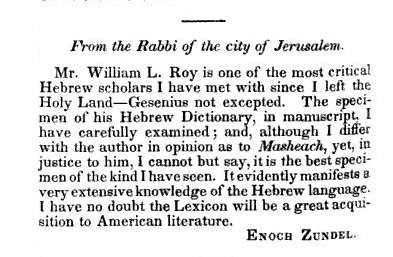

Here is the haskama, as printed in the second edition:

Pretty wild. It seems to say that he met Gesenius. (Gesenius, for those who don't know, was widely acknowledged as the greatest European modern Hebrew scholar of the 19th century. By comparison, Gesenius's praise of Shadal as "Italy's greatest Orientalist [Hebrew scholar]" was widely seen as high praise indeed. Of course the question of how great he was is complicated by the fact that you really couldn't compare a modern scholar at the time to Jews - perhaps that should be the subject of a future post.) Now, the idea that William L. Roy was as good a Hebrew scholar as Gesenius is a bad joke. Of course we don't know if Rabbi Chanoch Zundel was in any position to judge, if he really had any idea about Gesenius beyond meeting him, or if indeed any of this was true. It is extremely doubtful that the English was written by him, and it is possible that he simply signed whatever it is that Roy asked him to sign - of maybe he didn't even do that. Nevertheless, this testimonial appeared in both editions of Roy's book, and among other things, it was noticed and ridiculed in the press reviews.

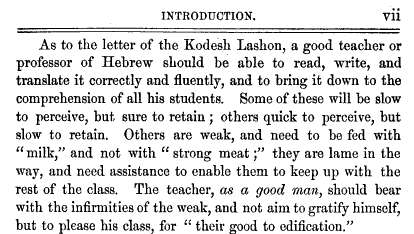

Before I get to those, here are some samples from Roy's introduction:

"That the Hebrew is of divine origin, is beyond doubt. We read in 2 Kings xvii. 28, that "Rabshaka stood and cried with a loud voice in the language of the Jews." Yehoodith is from Yehoo, a contraction of Yehovah, and dath, the law, religion. Hence the language of Jehovah, in which his law and religion were written."Elsewhere in the introduction he interprets Jesus's "not one jot or tittle" remark to refer to the yod and the . . . hirik. He then goes on to dismiss those who say that he meant an "accent." Roy disagrees with this, because instead of the Greek "Kereai" it would have used "milail." And besides, "an accent is as large as three hericks." He is thus taking the position that the nekkudot (points) were used in the time of Jesus.

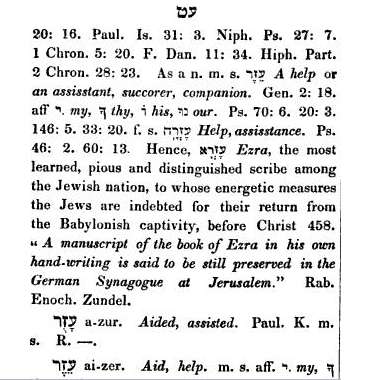

In his entry on the root עזר there's a little discussion about Ezra, which includes a little comment that he heard from the rabbi: "A manuscript of the book of Ezra, in his own hand-writing, is said to be still preserved in the German Synagogue at Jerusalem."

The American Review wrote a particularly bad review of the whole. The excerpt I am posting focuses on his use of Rabbi Enoch Zundel:

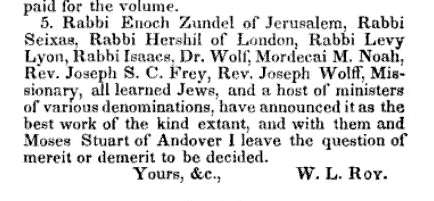

In the second edition, Roy responds to his critics and enlarges his list of Jewish approbators - whether he is telling the truth about Rabbi Solomon Hirschell of London or not, I cannot say. the others' were printed in the book:

The review continues to deplore the other approbations, including one from the chancellor of NYU, which it says dishonors New York City. It concludes by asserting that it has nothing personally against him, only the "empty pretences of his Preface . . . especially his pretensions to Rabbinic literature, by which he professes to correct the errors of other lexicographers. Rabbinic literature! Why, there are scarcely a dozen places in his Lexicon, where there is any ground to suppose he consulted the Rabbins; and even in these, we strongly suspect that he merely repeats what others had furnished to his hand." Finally, it ridicules his titling himself "Professor of Oriental Languages in New York, questioning whether he means New York State or New York City and - exactly to whom is he a professor?

Another review also focused on the . . . naive comment about a Torah written by Ezra and Roy's ready acceptance of it:

"We cannot avoid the feeling, as we turn over these pages, that he has contracted such an affinity for the Jewish grammarians, who have been held in repute among their countrymen, as to receive, with a too ready acquiescence, whatever comes from a Jewish source. In illustration of an apparently unsuspecting confidence, we refer to a remark introduced in connection with the author's statements, concerning Ezra; a remark, which indeed, is so worded as to possess no weight, but which yet is introduced in a quite grave and imposing manner. The remark is the following: "A manuscript of the book of Ezra, in his own hand-writing, is said to be still preserved in the German Synagogue at Jerusalem. Rab. Enoch Zundel." Credat Judaeus. Some other religious bodies in Jerusalem will show what are said to be bits of the true cross."Now, in fairness, it should be acknowledged that they are right to compare it to pieces of the "true cross" or a Rabba bar bar Chana story. BUT it should also be pointed out that this was 1836, and much of the rich discoveries of biblical archaeology and manuscripts sitting in dusty archives and corners of Europe and Asia were still unknown. No, there is no Torah of Ezra. But do you think in 1836 they dreamed of the Dead Sea Scrolls? They still hadn't found the Mesha Stele. The Cairo Geniza (admittedly, far younger than Ezra) was not at all known. 1800 year old Bibles still sat in desert monasteries. Codices like the one in Aleppo were still there, unknown or unexamined. No, none of these are Ezra scrolls, and it was naive to believe that such a thing existed (the Jews of Aleppo believed their prize was written by Ezra - it wasn't, but a real prize it was). But in a certain sense there was a failure of imagination. There were no biblical-era scrolls, but there could have been - and I don't think they realized that at all. Or, maybe I'm trying too hard to be even-handed. I digress.

Getting back to Roy, as I posted, he believed that the biblical name for the Hebrew language,

Kodesh Lashon? Seriously? That's English with Hebrew words. Ouch.

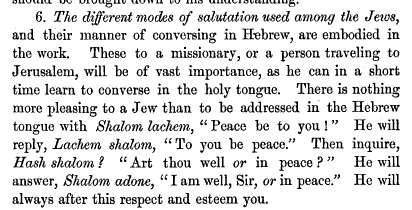

Secondly:

Yeaaaaah. I see.

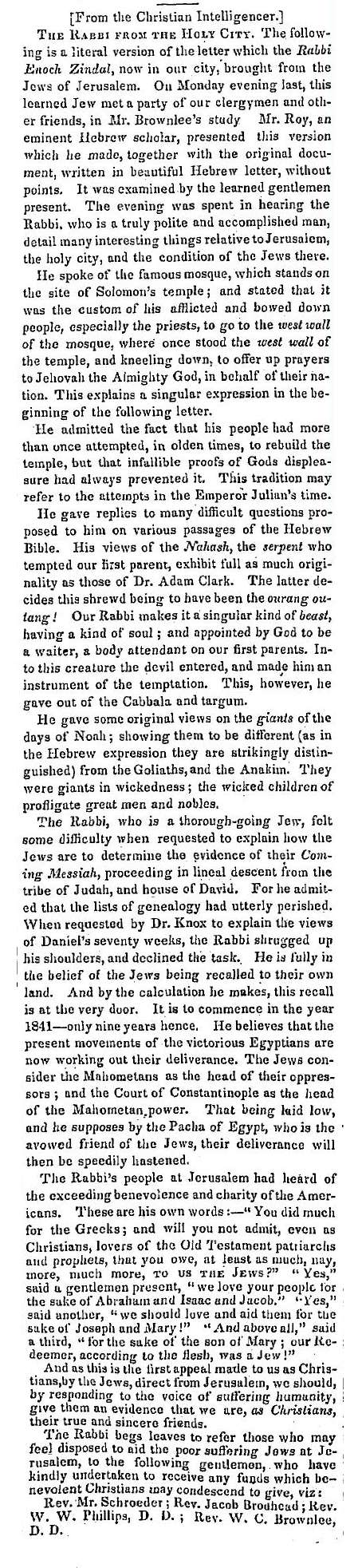

In any case, when he turned up in the New York, his presence was reported by the Christian Intelligencer. Here it is, reprinted in the Boston Investigator, December 14, 1832:

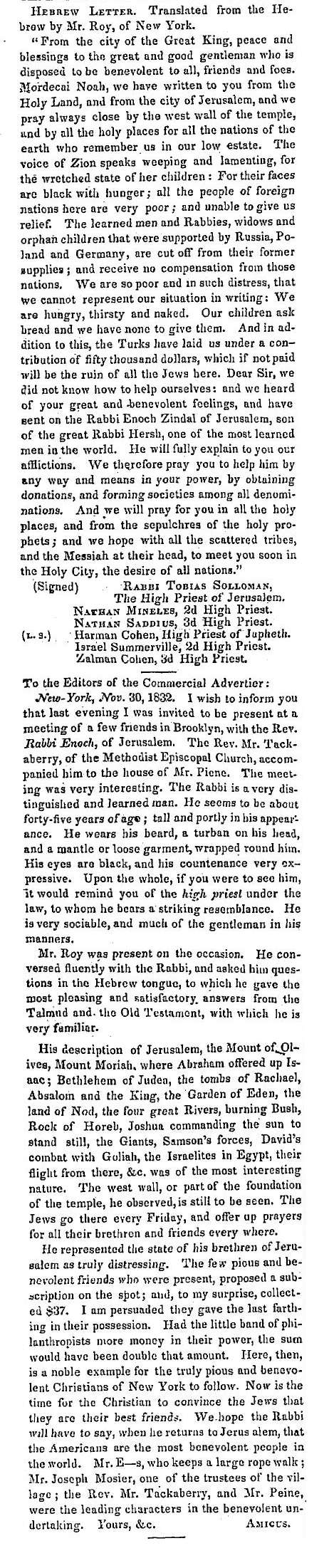

The also article also included Roy's translation of his letter from the rabbis of Jerusalem and Safed - addressed to Mordecai Manuel Noah:

This leads to the following question: which community was Rabbi Chanoch Zundel from? Was he from the Vilna Gaon's Perushim or the Chassidim? There is very little biographical information about him. It is known that he wound up in London, where he sat on Rabbi Solomon Hirschell's Bet Din for some time, adjudicating at least six cases. Writing in 1951, Abraham Ya'ari, is unable to determine which community he was a part of, and his scoop is that his father's name was Hirsch! (Yaari published a letter by Rabbi CZ in an article called "Letters of Jerusalemite Emissaries" in the 3rd volume of the periodical Jerusalem. As you can see, the English translation of the letter published in 1832 also shows his father's name.)

Now I know that more is probably known about him, and books and articles about Holy Land emissaries have already been written, but I haven't read them. So I'm going to try to determine if he was a Misnagid or a Chassid based on this letter. As you can see, it is signed by three rabbis of Jerusalem and three of Safed (Japeth; Good work reading Hebrew, Roy!)

I am guessing the following: In my opinion "Nathan Mineles" is none other than Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov's son Nathan, and "Nathan Saddius" is Rabbi Saadiah, a talmid of the Vilna Gaon's, son, who also was named Nathan Nata. I haven't yet identified the others, but I don't think I have to - I think it is conclusive that this is a letter from the Kollel Perushim, the talmidim of the Vilba Gaon, and therefore Rabbi Enoch Zundel was one himself.

Now that that's out the way, one more unusual thing bears pointing out. On September 5, 1836 The Herald of New York published a piece on the astounding news that the serpent (Hebrew nachash) in the Garden of Eden was not a serpent at all, but an orangutan. Apparently oranguatans were very popular entertainment at the time, because it informs he reader that he could see them on Broadway and in the Rockaways, at various hotels and elsewhere.

Two days later the paper jubilantly reported that when the article was pointed out to him, William L. Roy showed his dictionary - then being prepared for publication - where he writes the same thing, that nachash is cognate with Arabic nachasha, which means orangutan. And guess who agrees with this? You're right: Rabbi Enoch Zundel of Jerusalem:

This being 1836, the writer goes on to ascribe the "origin of the colored races of man" to a union of an orangutan and Eve, and that in all probability Cain was the son of this union, and was not Adam's son at all. This could well explain his murder of Abel, and serves as a warning against the mingling of races. Lovely - but you can't change the past.

Although I was only able to see Roy's second edition, it is interesting that in the entry he does NOT cite Rabbi Chanoch Zundel. I don't know if he removed it since the first edition, or if it didn't make it into the first edition at all - I also don't know why he would have removed it.

In fact this idea wasn't news in 1836. Its origin goes back to a Bible commentary written in1810. It's funny that the newspaper should have written in this fashion, but I guess it shows how long it takes for technical scholarship to filter down to the mainstream. The idea that the serpent (nachash) was an ape (and most likely an orangutan) was an idea of Adam Clarke (1760-1832), included in his monumental edition and commentary on the entire Bible (link).

In the first volume, (1810), in chapter III of Genesis he commences an involved discussion concerning the meaning of נחש, serpent. After showing its wide semantic usage in biblical Hebrew, he arrives at the primary meaning of "to view attentively" or "acquire knowledge" (citing Gen. 30:27). Next he notes that the Septuagint translation "ophis" (snake) is an insignificant objection, because that is merely what occurred to the uninspired Septuagint translators, who did not investigate the range of meaning of the word. That the New Testament also uses ophis is no matter, since the tendency in the NT is to quote the Septuagint. However, if we look to Arabic we find a root which is very similar to nachash - namely, chanas, a root which means "departed, seduced, slunk away." Various Arabic words built from this root include "akhnas" "khanasa" or "khanoos," all meaning "ape." Even more interesting, is that from the same root is "khanasa" which means "devil." Clarke writes "Is it not strange that the devil and the ape should have the same name, derived from the same root, and that root so very similar to the word in the text?" Thus, he thinks he has stumbled on a further range of semantic meaning, namely ape or seducer.

Next Clarke examines what the Bible has to say about the nachash in the Garden and what can be deduced from the story - he was more subtle than all other animals, he walked erect, had the gift of speech and the gift of reason. Furthermore, Eve evinces no surprise at the creature's behavior. Clarke immediately dismisses the possibility of it being a creature never known to speak, because if so then she would have been surprised, would have acted with caution in conversing with it. Clarke is able to readily dismiss the possibility that this creature was a serpent or snake. Snakes never walked erect. They have no organs for speech; they can only emit a hiss. He dismisses a comparison with Balaam's ass, for there God opened the ass's mouth. Here no such thing is intimated; in fact, speech was natural to the creature. The text itself testifies to it by explaining that it was more wise and intelligent than all other animals - and serpents are not particularly intelligent animals. However, apes are intelligent. Furthermore, one can plainly see by ape anatomy that it might have originally walked erect - "nothing less than a sovereign controlling power could induce them to put down hands in every respect formed like those of man, and walk like those creatures whose claw-armed paws prove them to have designed to walk on all fours. The subtlety, cunning, endlessly varied pranks and tricks of these creatures, show them, even now, to be wiser and more intelligent than any other creature, man alone excepted." Nowadays they walk on all fours and are obliged to gather food from the ground, so they literally eat the dust - even though they have the physical ability to pick out the dirt or even wash their food - but they don't.

As for the power of speech, the ape's chatter appears to be all that is left of an original gift of speech, removed as a result of God's curse. These . . . facts . . . plus the original difficulty with considering it to be a snake, and the similar and appropriate Arabic root, render it likely that the nachash was an ape, or the most intelligent and man-like of the apes - the orangutan. Finally, he ends his lengthy discussion with the plea to take it as only a suggestion which anyone can feel free to disagree: "If, however, any person should choose to differ from the opinion stated above, he is at perfect liberty so to do; I make it no article of faith, nor of Christian communion; I crave the same liberty to judge for myself, that I give to others, to which every man has an indisputable right, and I hope no man will call me a heretic, for departing in this respect from the common opinion, which appears to me to be so embarrasses as to be altogether unintelligible."