(Since it takes up four pages in his book, the extract above is from the London Saturday Journal of Aug. 24, 1839.)

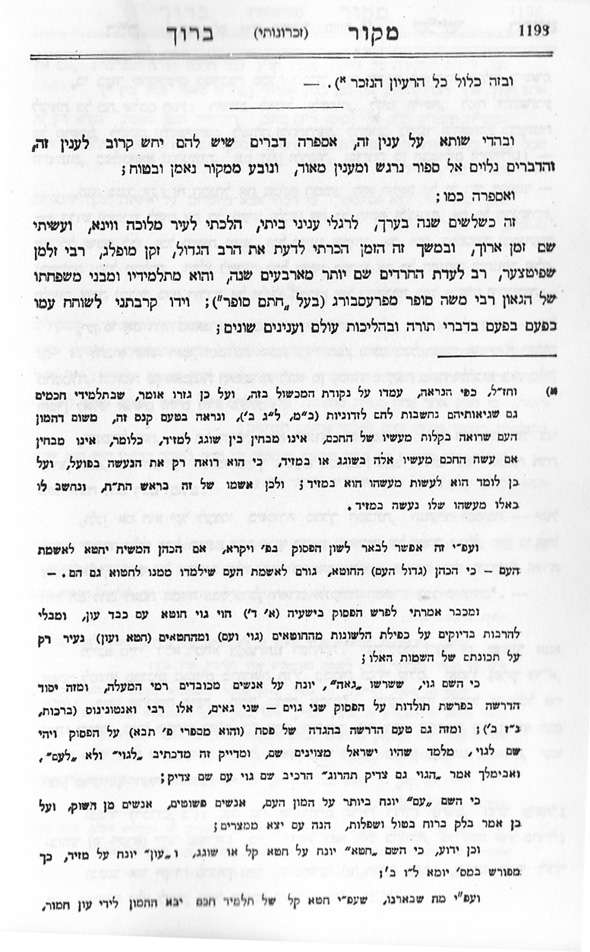

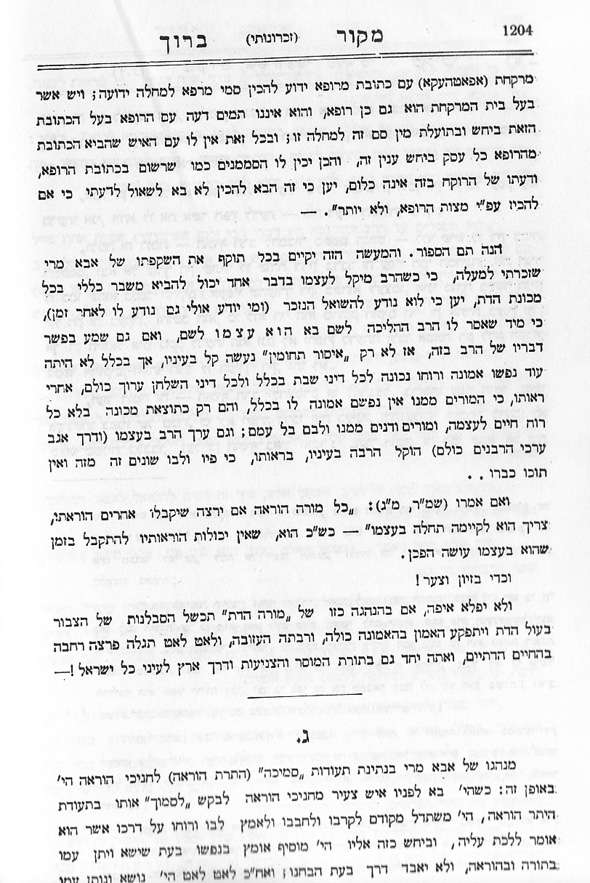

This reminded me of other stories of פוסקים who ruled strictly because of their adherence to the rules of פסק of but practiced leniently because of their lack of piety. The first story comes from Rabbi Baruch Epstein's Mekor Baruch (Vilna, 1928), v. iii pp. . Below is a partial English version of the story, and then the original Hebrew. ('My Uncle the Netziv,' a partial translation of a part of Mekor Baruch by Moshe Dombey is a very well known book due to well-known circumstances, but most do not realize that he published a second volume called 'RECOLLECTIONS The Torah Temima Recalls the Golden Age of European Jewry Rendered into English by Moshe Dombey Edited by N.T. Erline' (Targum Press, 1989):

At this time I want to mention a thing I've noticed many many times over the years. Many books translated from Hebrew use the most ridiculous transliteration of unfamiliar names of people and places. You can never go wrong if you write אלעזר פלעקלש without having a clue how that surname is pronounced, but once you try rendering it into English you run the risk of writing Eliezer Palklash (two absurdities in one) as he does on pg. 156 (should be Eleazar Fleckeles, although other spellings which basically convey this would do). Another book, a popular two-volume work on Jewish history by a notable Bible exegete renders עזריה די רוסי as "de Russo" (here the blame lies with his translator, who made many of those errors). These things detract from otherwise reasonable works.

Getting back to the excerpts above you can see that according to this story the rabbi renders a correct and strictly halachic decision for one who asks, but in practice didn't follow it since he felt that the halacha itself was incorrect, based on a misunderstanding by the rabbis of a biblical verse. When asked to explain himself, he says that the rabbi is like the pharmacist whose only role is to fill a prescription, not to debate it if he doesn't agree with it.

The rabbi is teasingly (and honorably) referred to by Rabbi Epstein as בפז, but he is Zacharias Frankel; the footnote gives it away to all but the most clueless. Rabbi Epstein instruct the reader that the euphemism is to be read left to right. Read that way, the first two letters are initials of his name. He even helpfully notes that the פ is to be read "f," not "p." The last initial is for the city in which his was ראש ישיבה, i.e., Breslau. In the first footnote (pp. 3-4) of Louis Jacobs' 'A Tree of Life' it is opined that it is "doubtful whether, in fact, Frankel actually said this, since it is contrary to his general philosophy of the halakhah." Unfortunately Jacobs says no more than this, but I think he meant that for Frankel, although halacha has a history, there can be no such thing as "the rabbis were wrong, so privately I won't listen to them." Alternatively, perhaps the story is true, but the identity of the rabbi is mistaken. Also interesting is that to Rabbi Epstein (writing possibly as late as 1923 when it was first published) and Rabbi Zalman Spitzer, the aged son-in-law of the Chasam Sofer, Zechariah Frankel was an Orthodox rabbi. A bad one, in their view, but they know nothing of Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch's contention, which is basically accepted today, that he was not Orthodox at all, or more likely they just ignore it.

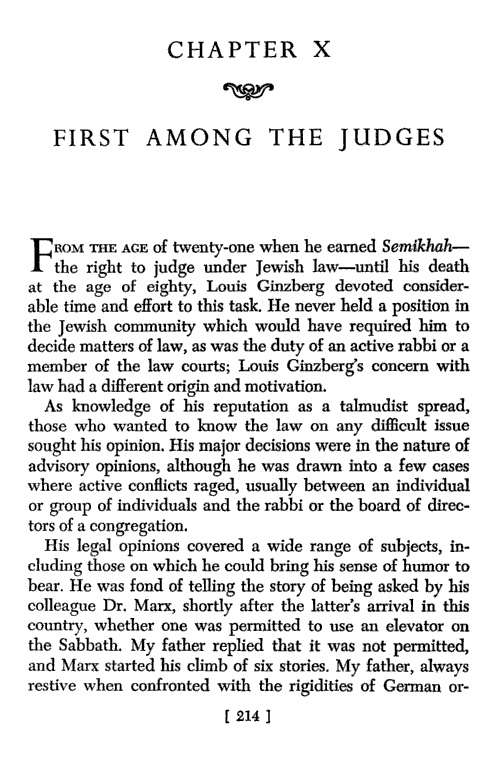

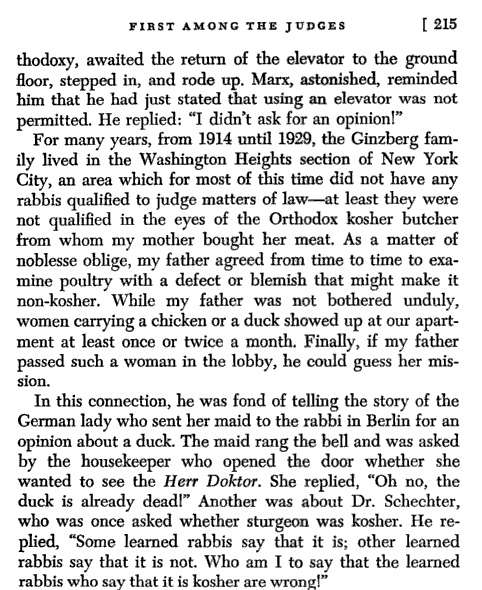

I blogged about the second story almost three years ago, concerning Alexander Marx asking Louis Ginsberg if one was permitted to ride an elevator on shabbos. The latter replied no, but then took the elevator to a high floor where he was waiting for Marx who had taken the staircase. When Marx registered his surprise, Ginzberg tells him "You asked what the law was, so I told you. I didn't ask!"

The truth is, I confess that I don't understand this precisely. The book is called 'Keeper of the Law,' and although this is not meant to imply that Louis Ginzberg was scrupulously careful in religious practice, observant he was supposed to be. This story has him not merely bending the law, but flouting it. However, the book was written by Louis Ginzberg's son Eli, who acknowledged that he himself didn't really understand much about Jewish learning. It is possible that Ginzberg had halachic reasons for leniency and thus was not violating what he knew to be the halacha. That this may be the case is hinted at by Eli's telling of his "father, always restive when confronted with the rigidities of German orthodoxy." That he was fond of telling this story and considered it humorous, and a joke at the expense of Alexander Marx ("the rigidities of German orthodoxy") lend further support for this interpretation.

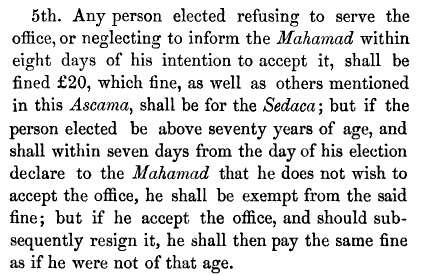

All in all, here we have three versions of what are essentially one story. The first is reported by Isaac D'israeli (although it's unclear if he's made it up, or if it was an illustrative anecdote in the form a joke, etc.). D'israeli, it will be recalled, allowed his children to be converted to Christianity as part of his gradual response to London's Bevis Marks Synagogue hierarchy's election of him as a member of the Mahamad in 1813. Not religious in the best of times, D'israeli wanted nothing less than to be a synagogue officer. The rules of the synagogue stated that members couldn't refuse election or they'd face a hefty fine. The coercion outraged him, and he consented to have his children baptized into the Church of England instead, one of whom later gained fame as a novelist, although others might argue that Benjamin Disraeli's fame was as British Prime Minister.

Perhaps this sounds bizarre, but below you can see this rule in print, still extant in the very same synagogue in 1872, although by then the fine was half what it was in 1813. Bear in mind that in today's money £40 is almost $3000!

Although in the broad sense D'israeli wrote sympathetically of Judaism, clearly he found those who handled the rules, if not the rules themselves, utterly ridiculous. Thus his story of the rabbi who paskened that you can't eat a peacock, but ate it himself because his father paskened you can!

The second story, about Rabbi Zecharia Frankel may or may not be true, but it encapsulates very well the attitude of traditional Orthodox rabbis toward those of their colleagues who don't tamper with the halacha, but think in an unorthodox way.

The third story, concerning Ginzberg and the elevator, has the distinct advantage over the others in probably being mostly true (it is reported by his son that he was fond of telling it). However, it's unclear what was really going on there. What is clear though is that it's the opposite of those rabbis who pasken leniently, often for gain (as in kashrut or eruvin), but practice strictly themselves.