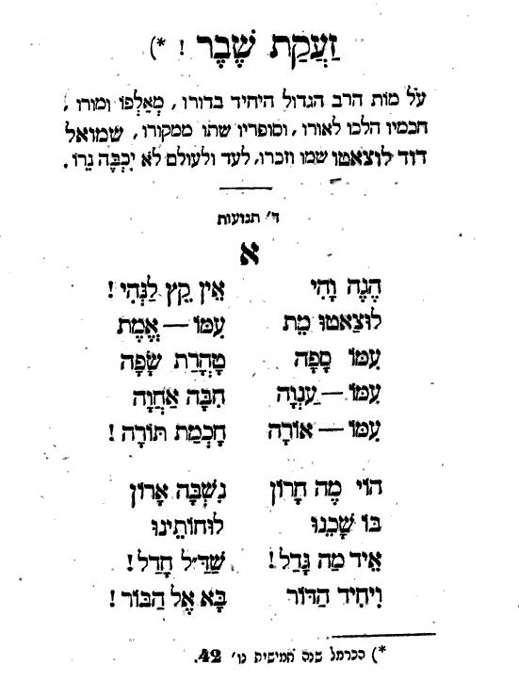

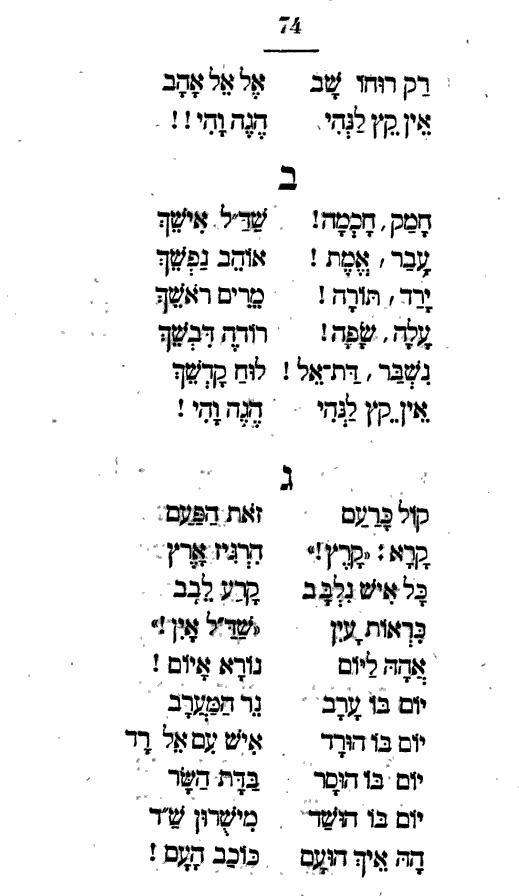

It was originally published in Hamaggid 11-15-1865 pg 349. If you're the sort of person who likes to see it in the original, you can click below to enlarge:

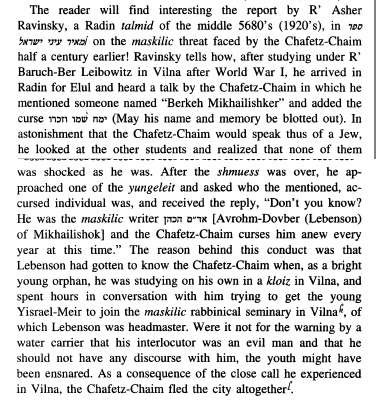

Adam Ha-kohen is depicted below, bottom left:

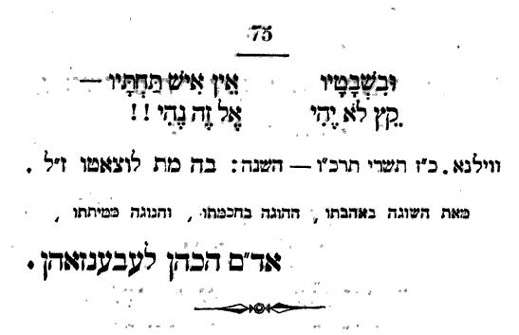

Interestingly, here is a mention of Adam Ha-kohen on the Yated web site:

Once, somebody came to Rav Simcha Zissel on erev Shabbos when it was almost Shabbos, to give him a piece of good news, namely that Adam Hacohen, yemach shemo, the leader of the maskilim had died.What's amazing about this piece is that the author, a famous maggid, appears to me to miss and undermine the mussar message he was trying to bring out! It's one thing to say that the Chofetz Chaim used it because he felt it was appropriate given his personal experience. It's another thing to use the phrase yourself even as you mention that the great ba'al mussar R. Simcha Zissel felt that the proper attitude toward him after his death was pity. Can that be squared with an epithet like yemach shemo?

(I apply the wish yemach shemo to that rosho because the Chofetz Chaim also did, explaining that he didn't use the phrase about any Jew, with the sole exception of Adam Hacohen who destroyed and ruined many Jews. The Chofetz Chaim related that the maskilim used to search for gifted individuals, whom they would send to university in Berlin. He said that when he was fifteen, they tried to lead him off the right path R'l, but that boruch Hashem, was saved from them. That was the reason that he said yemach shemo.)

On that Shabbos, following the news that Adam Hacohen had died, HaRav Simcha Zissel's face wore its usual pale complexion, as he said, "Now he sees the truth, how he deserves to be pitied . . . " Rav Simcha Zissel was exemplary in the trait of sharing others' burdens with them. Thus, after the man had died and was no longer able to ruin others, he exclaimed that he deserved pity.

link.

In any case, this is a well known piece of Lithuanian yeshiva lore. Another Yated article mentions it along with the evident source. Below is the discussion about it in Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky's Making of a Godol, which is worth reproducing even though it basically comes from the same source (pp. 264-65; however I combined it into one image):

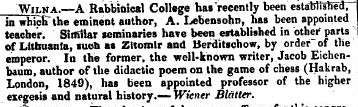

I'm a firm believer that history is best illustrated not only by quotes from primary sources, but whenever possible to see the sources themselves. In this role there's nothing quite like newspaper and periodical articles to awaken the awareness that history was once current events. For me and many readers, this is best seen in English, where another layer of foreignness, and hence remoteness, is removed. Below is a news blurb in the October 4, 1850 edition of the Jewish Chronicle:

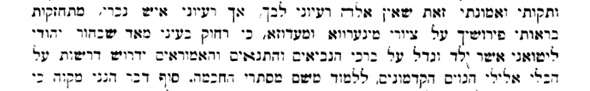

Also of interest, see Iggerot Shadal Vol. 2 pg. 1093:

Here, in a letter dated 10-2-1850, Shadal chides Adam Ha-kohen's son Michael (also known as Micha) Yoseph Lebensohn, who is considered by many to have excelled his father as a Hebrew poet (he's also depicted above, upper left). He would send Shadal his poems for judgment and criticism, and he would respond. Here Shadal is chiding him for his references in his poem קֹהֶלֶת to Minerva and Medusa. It's very hard for him to understand, writes Shadal, how a Jewish Lithuanian bochur reared on a diet of the Prophets, the Tannaim and the Amoraim could be inspired to write poetry by the Greek gods of old.

The issue of classical imagery in Jewish literature is a very interesting one, and deserves a post some time. There is one very notable example, of a great posek whose poetry included such imagery. Suffice it to say, while it was perfectly consistent for Shadal to be dismayed by Hebrew poetry inspired by Greek thought, such imagery was far from absent in Italian Hebrew poetry. But Italian Jewish culture was Italian Jewish culture. Here Shadal appears to be particularly dismayed to see such an incursion into Lithuanian Jewish culture. What's a Litvak bochur doing writing about Medusa?

To me, the mussar lesson is not that one of the greatest of the maskilim felt this way, but that despite having such a sharp disagreement and criticism of the very approach the young man had taken, he still loved him, wanted to dialog with him and be a positive influence on him.