Parts of his monumental Mishnah commentary were published in 1655 in the original Judeo-Arabic, with a Latin translation, by Edward Pococke in his Porta Mosis (also given the Arabic title באב מוסי, or "Bab Mosi," which is cognate with the familiar Aramaic term בבא, which also means portal).

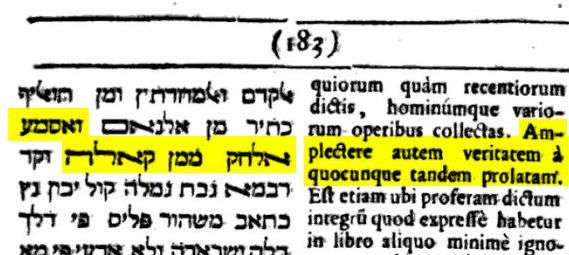

Here is how it appears:

Ibn Tibbon's famous Hebrew translation of ואסמע אלחק ממן קאלה is ושמע האמת ממי שאמרו. Far be it from me to play Rambam exegete, but it occurs to me that Ibn Tibbon was very smart to translate סמע literally to its Hebrew cognate שמע, which usually means to hear. While it could mean "accept" (indeed, R. Kapach [sic] changed Ibn Tibbon's שמע, hear, to קבל, accept) I'm not sure that was the Rambam's intention. After all, the huge problem everyone encounters is that what is true is not always apparent or can't be tested. What does it mean to accept the truth when so many issues are inexact, to say the least? If he meant "hear the truth," it becomes much easier to understand. Maybe you're in a position to accept it, maybe not. Maybe the position is true, maybe not. But at least listen. (The preceding was homiletical, and almost certainly not what he meant. Still, food for thought.)

As for the language, a long time ago Judeo-Arabic was discussed in the comments to one of my posts, and the question of why the Jews in Spain preferred to write some of their highest level religious texts in Arabic, from responsa to investigations into Hebrew language and grammar to commentaries like these (according to medieval sources the entire Talmud was even translated to Arabic, although I doubt it), while almost every other Jewish society right up to the modern period and even to the present, they always used Hebrew for their most serious and authoritative texts. In addition, the Judeo-Arab texts use loads of very Islamic terminology as exact equivalents of Jewish terms. 'Halacha' is 'alsharia' and 'teshuva' is 'fatwa,' and so forth.

I posited that the chief difference was Arabic itself, which had two qualities that other Jewish vernaculars did not have. First, it was similar to Aramaic (and Hebrew), underscoring the fact that the Talmud and Targums were written in vernacular language. Second, the phenomenon of diglossia (one language for scholarship and one for speech) was far, far more marked in Christian society. Arabic was both the classical language of prestige and the vernacular.

In fact, as European vernaculars rose in prestige, with scholars creating lexicons and investigating their own spoken tongue, scholarship too began to be written in those languages, and the Jews in Europe too began writing scholarship in the vernacular they considered prestigious (i.e., correct Italian, German and French). Writing the vernacular in the Hebrew alphabet ultimately fell out of fashion due to other considerations, such as the widespread ability to read and write the Latin alphabet. Perhaps another difference is that the Jews perceived Islam very differently from how Jews perceived Christianity. Many parallels, from ablutions, to fixed times for prayer, to beards, to circumcision, to fasts, to nidda, to halacha/ sharia, to a body of oral teachings, etc. made "sharia" seem a lot more like "halacha" and rabbis like 'ulema' than anything found in Christendom, where these religious similarities were not only missing, but many more differences could be found. In those lands the Christians didn't esteem their own spoken language, and neither did the Jews.