Rabbi Lewin was requested to produce it in two weeks, but it didn't appear until six years later. It was then published in 1778 under the title Ritualgesetze der Juden. Judging by the title page this work seemed to be a collaboration between Lewin and Moses Mendelssohn, in fact it was really the work of Mendelssohn. The rabbi, who was a good friend of Mendelssohn, only reviewed it and made necessary corrections.

Below are two reviews of this work (admittedly they don't tell us much) which appeared in British periodicals:

1.

2.

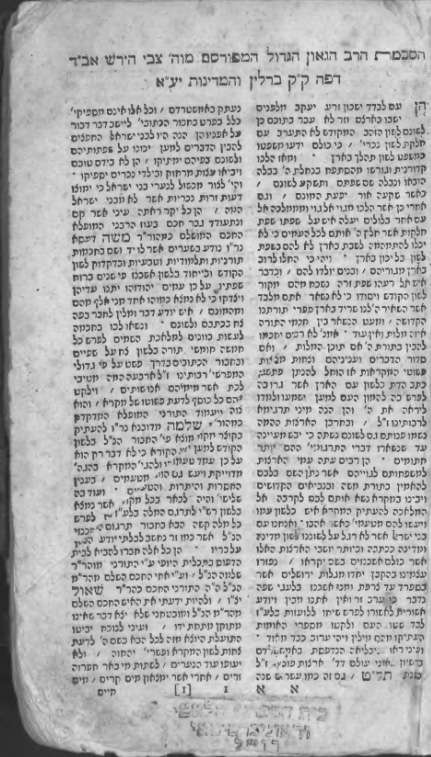

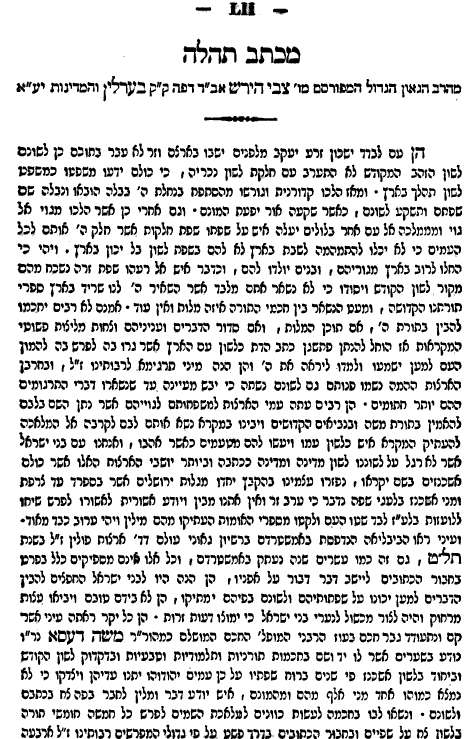

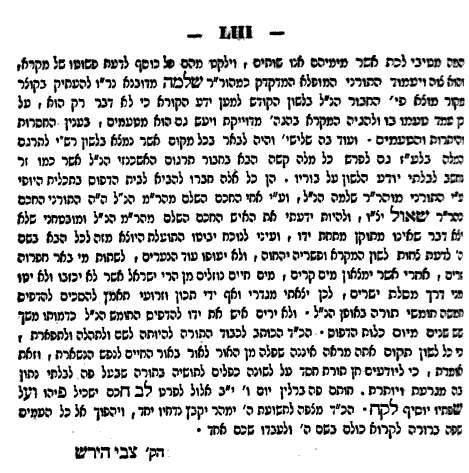

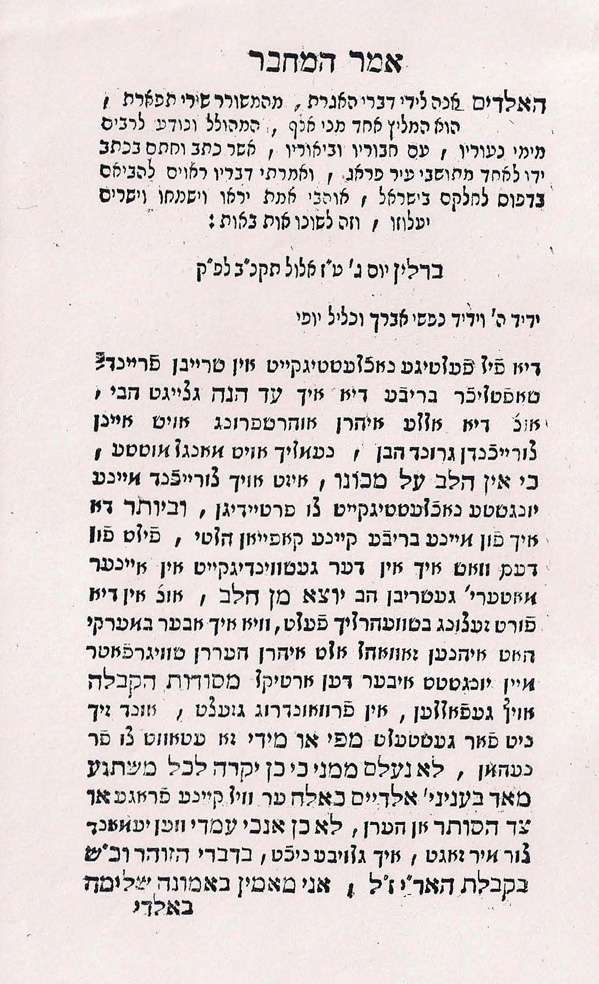

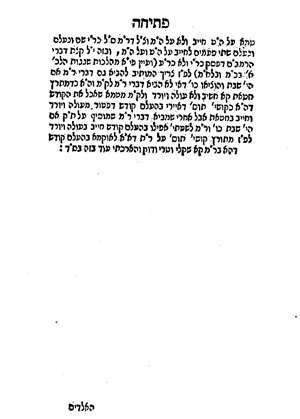

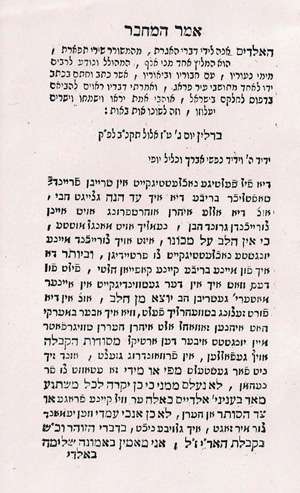

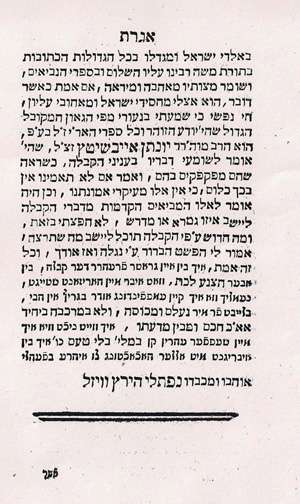

Rabbi Lewin was a good friend of Mendelssohn's. He was among the only rabbis whom Mendelssohn asked for an approbation for his Pentateuch translation, and certainly among the only rabbis at the time to specifically concur with the need for a a modern Jewish translation into the vernacular. The complete text of his haskamah to Mendelssohn's Biur (ie Chumash Nesivaus Scholaum) was only included in the very first edition of 1783 (at the beginning of the 2nd volume, Exodus). Excerpts from it were published in Landshuth's biography of Lewin. The entire piece, however, was printed at the beginning of the Romm edition printed in Vilna 1849. Here is the original followed by the more readable Romm version:

This approbation includes the observation that the Gentiles believe in the Torah and prophets, understood them and have made vernacular translations of the Bible. Yet the Jews, especially the Ashkenazim, don't speak a clear language (*coughYiddishcough*). He writes that he's seen a Yiddish Bible printed in Amsterdam in 1679, and also another one, both of which are greatly wanting, but they were the only ones available for Jews who wanted to understand Scripture. However, there were the impressive non-Jewish translations, and these are stumbling-blocks for young people. So it is that an honorable rabbi, scholar and sage, famous and expert in Torah, Talmud, science, Hebrew grammar and the German language, not one in a thousand is like him -- Mendelssohn -- has written such a needed translation . . .

Although this approbation was written in Berlin in 1778, it has been noted that their friendship dates at least as far back as 1764 - 1770, when Lewin served as rabbi in Halberstadt. In Geiger's JZWL 1872 pg. 232 a letter is printed, written in August, 1770, in which the poet Gleim informs F. E. Boyzen that Rabbi Lewin ("Herr Loebel") was an admirer and friend of Mendelssohn. (This letter is also reproduced in Latin letters in Landshuth's Toldos Anshe Hashem U-peulosam be-adass Berlin pg. 83) There is a possible earlier connection: in 1756 a German translation of sermon of Rabbi David Frankel, author of the Korban ha-Edah commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, was printed. Shortly thereafter followed an English translation, which was reprinted many times, including in America! Rabbi Frankel was Mendelssohn's rebbe; he was also Rabbi Lewin's first cousin. It was, in fact, Mendelssohn himself who had made the German translation of Rabbi Frankel's sermon (see Gad Freudenthal's article in the EJJS 1 on this sermon). At the time Rabbi Hirsch Lewin was beginning to serve as Rabbi Hart Lyon in London, where the English version of the sermon appeared. Although I've no proof to give of any involvement on the part of the rabbi, much less that he and Mendelssohn knew one another yet, one might say that their circles overlapped even at this early period, although Lewin was eight years older than Mendelssohn.

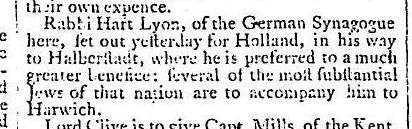

Here's a notice of the rabbi's leave of England toward his post in Halberstadt (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (London England) Wednesday May 23 1764):

Ultimately their friendship was tested over a notorious incident, namely the Wessely Divre Shalom ve-Emes affair. Demonstrating that one can't always predict affinities and affiliations -- as I will elaborate -- Rabbi Lewin was outraged by Wessely's pamphlet in which he called for a restructuring of the Jewish educational system (or some might say, he called for structuring that "system") and insulted the rabbis. He was so upset that he sought to toss Wessely out of Berlin. Wessely was Mendelssohn's close friend, and their varying viewpoints came between the rabbi and the philosopher. Eventually Lewin made it clear that either Wessely goes or he goes. In fact, neither went.

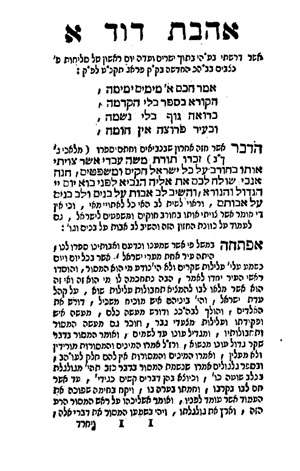

What I meant by not being able to predict affinities was that one of Mendelssohn's fiercest rabbinic critics, Rabbi Elazar Fleckeles, the foremost student of the Noda Beyehuda, appears to have held a fairly mild, and even positive view of Wessely. In addition to quoting him several times in his writings, it seems they also had a correspondence, although I'm not sure how extensive. In 1800 Rabbi Fleckeles published Ahavat David, a stridently anti-Frankist/ anti-Sabbatian tract, based upon sermons he had given on the subject (see this excellent post by Rabbi Eliezer Brodt). The book included a 1796 letter from Wessely, which Fleckeles offered as evidence that Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschutz was innocent of Sabbatianism! I'll get to the content of the letter in a moment, but first I will just note that I examined the pdf of Ahavas David twice, and I was unable to find the letter. I couldn't understand why I couldn't find it, so I asked several friends (literary men) if they knew what page it was on. Dr. Marc Shapiro replied that this edition -- a Copy Corner reprint -- is censored; it doesn't include the letter! I suppose it's theoretically possible that the censorship, ie, removal of the letter occurred long before the scanning of the book. That is to say, there's no way at the moment to tell who removed it and when, but we can probably guess why. In any case, at the same time I asked Shapiro for clarification, Rabbi Brodt told me that his copy of Ahavas David includes the letter, and he sent it to me. Here it is:

As you can see, Wessely writes:

"By my life, I heard in my youth from the mouth of the great kabbalist, who knew the Zohar and all the works of the Ari by heart, the rabbi, my master, Rabbi Jonathan Eybeshutz ZZ"L, that he used to say to his audience when they were hesitant to accept a kabbalistic teaching, 'if you don't believe it, it's no matter, because it isn't from the fundamentals of faith.' So he used to say to those who brought kabbalistic teachings to explain a piece of Gemara or Midrash, 'I don't desire this. What's the use? According to kabbalah you can explain anything you want to; just tell me the simple meaning via "niglah"' -- it's completely true!"One imagines that Rabbi Fleckeles sought such information which had the two-fold advantage of showing that a great Kabbalist like Rabbi Eybeschutz ultimately marginalized kabbalah, something which was important in combating Frankists and the vestigial Sabbatean movement. Secondly, it also strongly suggested that Rabbi Eybeschutz himself was innocent of the charge that he himself was a secret Sabbatean. As a student of Eybeschutz, Wessely was in position to recall his master's views for the benefit of Rabbi Fleckeles, nearly 30 years his junior, who was only 10 years old when Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschutz died.

Actually, it's a crude case of censorship, because the eagle-eyed reader could notice that the last page of the introduction promises that the first word on the following page will be האלדים. Instead the first word is אשר. As you can see, when these two pages are inserted properly the leading words are quite correct:

In any case, the complete letter was also printed in Hameliz 48 pg. 750, May 7, 1886:

Finally, it doesn't seem inappropriate to add something interesting relating to the controversial son of Rabbi Lewin, Saul Berlin (1740-1794), known as the forger of the Responsa Besamim Rosh. In 1844 an old man living in London named Meyer Joseph submitted a piece for Julius Furst's Literaturblatt des Orients. Joseph had been a close friend of Saul Berlin in his youth:

It was in the year 1794 when this exceptional man died here, and I think I have the right to publish this article as I was the only friend he had here. He was on a long journey, the object of which I do not remember anymore, and intended also to stay in London for some time. I visited him daily, we remained often together for hours at a time, and, although I am now 83 years old, the impression he made upon me, his eloquence and his whole personality remain unforgettable to me. A few months after his arrival he fell ill with cramp and it was I who closed his dying eyes. On his death the London community paid him respect. He was buried with great honors on the 25th of Marcheshvan, 1794. On arranging the things he left behind him I found his will, which I then copied for myself. (translation by David S. Katz in 'The Jews in the History of England,' 1485-1850, pg. 325, except that he translated "Heshvan" while I preserved the "Marcheshwan" of Joseph's original) The piece included the will, which Joseph himself copied:

Writing to the Jewish Chronicle on October 4, 1935, Cecil Roth noted that as Yom Kippur approaches, it should be noted that in "most London synagogues" there is Yizkar recitation of a list of rabbis, but it seemed this custom was on the wane. So as to "refresh [the] memories" Roth included a list of the 10 rabbis. Number 6 is Rabbi Saul ben Rabbi Zevi, ie, Saul Berlin. His name is included in the list "out of compliment to his father, and in view of the fact that he died in London."

[1] Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch ben Aryeh Leib ha-Levi (1721-1800), also known to history as Hart Lyon, was the Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi in London between 1757 and 1763. He was appointed Chief Rabbi of Berlin in 1772. His youngest son Zalman (1761-1842) would achieve fame as Rabbi Solomon Hirschell of London. Another son, Saul would achieve notoriety as the presumed forger of the Besamim Rosh.

Here is his portrait:

Many thanks to Rabbi Eliezer Brodt, who sent me much valuable information regarding Rabbi Fleckeles and his attitude toward the Zohar.

Update: November 22, 2010 - Recently HebrewBooks added an uncensored version from the Chaim Elozor Reich Collection, which you can access here.