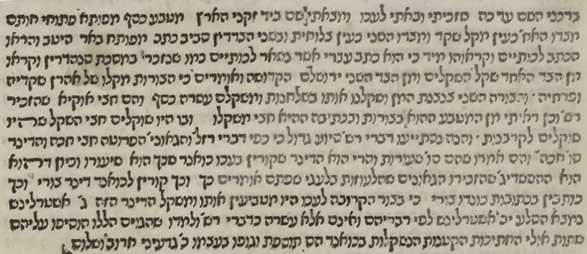

In Acre he learned that some elders possessed an ancient silver coin. Engraved upon one side was a branch of an almond tree, and on the other side a jar. There was some writing on both sides. Unable to decipher the script, they showed the coin to some Samaritans who could read it without hesitation, since the ancient Hebrew script is used by them, as mentioned in Tractate Sanhederin. On one side it read שקל השקלים, sheqel of sheqels, and on the other ירושלם הקדשה, Holy Jerusalem. The Samaritans explained that the branch is the rod of Aaron and the jar is the jar of manna. Weighing it on a scale, they were able to see that it weighed 10 pieces of silver, which is equal to half an ounce, as indicated by Rashi. He also saw a coin with the same emblems which weighed half the weight of this coin, which could be used to weight out the amount used for the sacrifices.

However, in the commentary itself he had questioned Rashi's measure (Exodus 30.13):

Rashi wrote (Exodus 21.32): "A sheqel weighs four gold coins, making half an ounce according to the correct weight of Cologne." This is based on the Gemara, which gives such an equivalence (i.e., gold and silver denars had the same weight). Ramban goes on to cite sources which assert that gold coins no longer weighed what they once did, while Rashi seems to be assuming that the weight remained constant (and that is why he cites the gold coins of Cologne). According to the Halakhot Gedolot and the Rif, "our" gold coins are almost a third smaller than those in the time of the Talmud. They therefore opined that a sheqel would weigh 3/4th of an ounce, and this is the opinion Ramban seems to accept. However, his later experience with what seemed to be actual sheqalim show Rashi to have been entirely correct.

(Both images are from the 1490 Naples edition.)

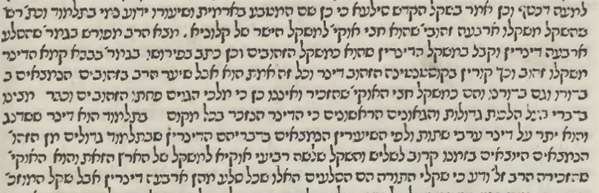

This passage became quite famous to anyone interested in what the ancient shekalim, as well as the ancient Hebrew, looked like. Rabbi Azariah dei Rossi quotes this passage in the 56th chapter of Meor Enayim, which is titled על האותיות של כתב עבר הנהר ושקל הקדש. The book included engravings of a table of the Samaritan alphabet as compared with the Hebrew, and copies of both sides of such a sheqel as described by the Ramban (see here). What were his source for these images?

For the alphabetical table, de Rossi writes:

He had thus seen no less than three examples of this alphabet. The first was a page written by a trustworthy person from the land of Israel for Rabbi Petachya Yada of Spoleto, to whom the former had been teaching Arabic. His son showed it to de Rossi. The second was an autograph manuscript of Rabbi Moses Basola (1480-1560) describing things which he had seen on his journey. (This account remained unpublished until 1785, when it was printed for the first time in Livorno under the name Masaot Eretz Yisrael.) The third is a text shown to him in Mantua by Rabbi Reuben of Perugia. The text had been given to him by a Christian scholar in Bologna.

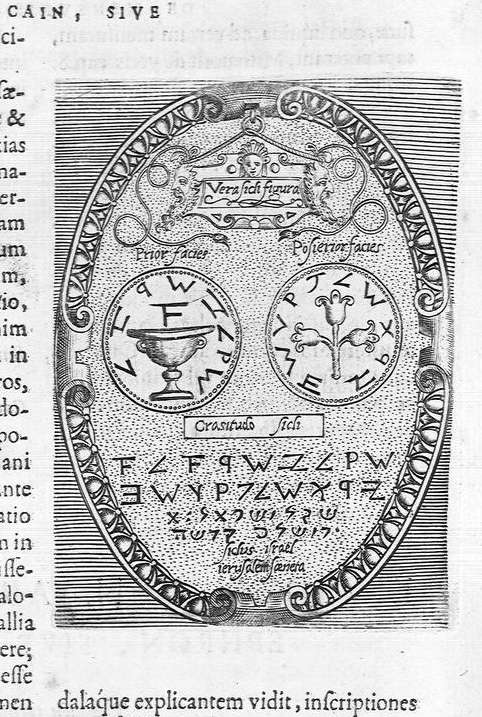

As for the sheqel, de Rossi writes that one of them was in the possession of the widow of Isaac Haggio of Ferrara. He had moved to Jerusalem, where he died. So his widow who still had children to care for moved in with her son Rabbi Yom Tov in Ferrara, where he managed his father's estate. It was this coin which de Rossi had seen, and which is pictured in his book. He writes that the coin read שקל ישראל on one side, and ירושלים הקדושה on the other. In addition, there were the letters שד on the שקל side. De Rossi offers the suggestion that שד stood for שקל דוד, however we are in a position to realize that it stood for שנה דל"ת, that is Year Four, as in the 4th year of the establishment of the Hasmonean House, or the revolution against the Romans, i.e, 70 CE. The reason we realize this is because in our time we don't have to scrape together evidence, and we have coins which read שא and so forth. Indeed, I have seen many examples from the 18th century where it is recognized that these are acronyms for years. There are 5 such coins, corresponding to years 1 through 5.

As for the discrepancy between the Ramban's שקל השקלים and the coin which de Rossi himself saw, which read שקל ישראל, he assumes that writing from memory, the Ramban transcribed mistakenly. De Rossi then discusses whether the other side should be read ירושלים הקדושה or ירושלימה קדושה, relating this to a passage in the Jerusalem Talmud where it is reported that the people of Jerusalem would write ירושלימה in place of ירושלים. In addition, this grammatical tendency even explains a position of Beit Shammai on permissible levirate marriages!

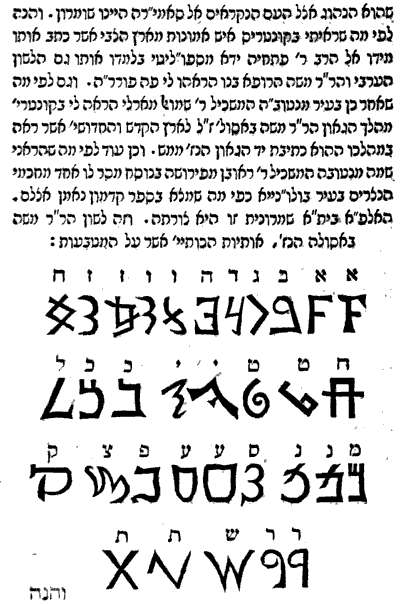

Although the Meor Enayim was first published in 1573 this is not the first time that an image of an ancient shekel was printed. In 1538 a very unusual scholar named Guillaume Postel printed a book called Linguarum Duodecim Characteribus Differentium Alphabetum, or an introduction to 12 alphabets. The following appeared on the 22nd page:

Postel was a Christian kabbalist who played a minor but notable role in the very first printing of the Zohar. He had been working on a Latin translation of the Zohar and Bahir, but considered it only proper that the original Aramaic version be printed first. To this end he encouraged Rabbi Moshe Basola -- the same Rabbi Moshe whose travel manuscript contained the Samaritan alphabet and was consulted by De Rossi -- to print the Zohar. Basola was involved in having this accomplished in some way, which is not entirely clear to me, but his approbation does adorn the תקוני הזהר published in Mantua in 1558:

This kabbalist, about whom it is reported that Rabbi Moshe Cordovero kissed his hand upon meeting him, dates his approbation "February":

Interestingly enough, Rabbi Moshe Basola appears on the Dei'ah VeDibur web site three times: as "HaRav Moshe Basola", "Rabbi Moses Basola"and "itinerant traveler Moshe Basola." More trivia: his grandson was the rabbi Mosè della Rocca for whom Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Modena wrote his incredible bi-lingual poem קינה שמור at age 13.

Postel was unusual in other respects. In a Hebrew book about the mystical significance of the menorah, which he called אור נרות המנורה, he refers to himself as איש כפר סכניא ושמו אליהו כל-משכליה שנתגייר לחיבתו של ישראל. The great Konrad Pellikanus translated this book into Latin the following year, under the title Candelabri typici in Mosis Tabernaculo, but he left this line untranslated! This of course doesn't mean to say that he converted to Judaism, but evidently he was some kind of Judaizer, and one learned enough in Talmudic lore to adorn himself with the nom de guerre of a Christian who appears in the Talmud.

Although Postel's was the very first image of an ancient shekel to be printed, in an article called "Shekel Medals and False Shekels" Bruno Kisch drew attention to what he considered a far superior early publication, which also preceded the one in Meor Enayim.

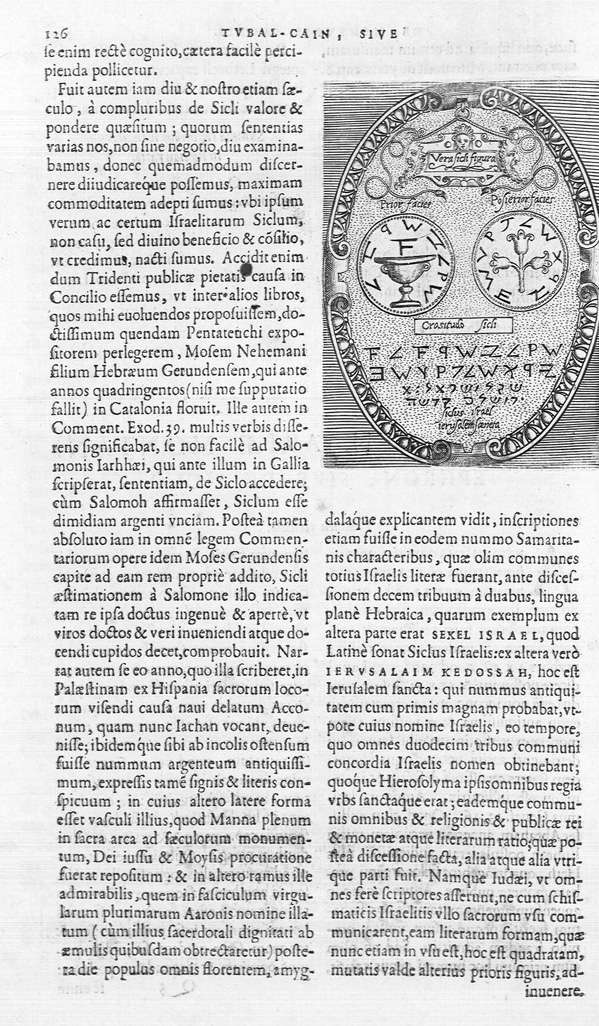

This is from Arius Montanus' Antiquitatum Judaicarum Libri IX (Leyden, 1593 - this is from the second printing, but the first was printed at the end of the Antwerp Polyglot Bible in 1572, thus prior to de Rossi's Meor Enayim, printed in 1573).

Here is the full page, in which he recounts that while participating in the Tridentine Council (1545-1563) he was studying the Ramban's commentary on the Torah (Mosem Nehemani filium Hebraeum Gerundensem is the Ramban). On the very night when he'd studied the bit about the shekel, he received 13 ancient gold coins from an archbishop friend, who asked his expert opinion about them as an antiquarian. He was told that he could choose one to keep as payment. One of them was not gold, but was a genuine silver shekel!