So here begins post #1 in this series.

Shadal's comment to Genesis 2:4 is quite interesting, because he tries to determine the correct pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) using internal evidence. Strictly speaking the first part doesn't pertain to the pronunciation, but as an introduction to his view which he gives later it is essential. I'll give an image of the comment as it appears in the Pentateuch published in Padua 1871, followed by my rendering of it, followed by some remarks.

Regarding the pronunciation of this name [YHVH] there is no doubt that all through the days of the First Temple and also in the early days of the Second Temple this name was pronounced as it is written, for we see that there are many theoporic names formed from this word (i.e, YHV- or -YHV) during that period. For example, Yehonatan, Yehoyada, Yehoshaphat, Yehoram, Yehoachaz, Achazyahu, Chizkiyahu, Yeshayahu, Yirmiyahu, etc. Also, if they did not read it then why would they write it?

It seems that sometime during the Second Temple period the Sages ordained that one should not read it as it is written. Perhaps they did this because they saw that the people were transgressing the Third Commandment, taking God's name in vain. They decreed that the word connoting Lordship should be said instead (i.e., Adonay). We see evidence of this from the Greek translation ascribed to the 70 where the name YHVH is translated in each place as Κύριος. So too in the Latin Vulgate it is translated as Dominus. Similarly in what remains of the work of Origen called the Hexapla we see next to his Greek translation a column of Hebrew words transcribed with Greek letters. In each place where it is written YHWH we see Αδοναι.Similarly those who added the nekkudot to the Biblical text meant for us to pronounce it using the term denoting Lordship, for which we find four proofs:1) They treated the בג"ד כפ"ת letters following YHWH as hard (pointed with a dagesh), rather than soft. (He supplies three biblical texts illustrating this to be the case, which shows that even though the last vowel of the Tetrragrammaton is pointed -ah they meant for it to be pronounced -ay as in adonay.)2) They pointed the letters וכל"ב appearing before it (i.e., YHVH, meant to be pronounced adonay) with a patach and not a chirik (i.e., vadonay, ladonay, etc. This shows that the first vowel should be Ah-. Showing this is necessary because in truth YHVH is written with a sheva for the first vowel).3) They pointed a מ at the beginning with a tzéré rather than a chirik (i.e., méadonay, showing, again, that the first vowel should be Ah-).4) They did not point YHVH in the same way in every place. Sometimes they pointed it with the same vowels used in Elohim; this usage is found before and after the name of Lordship (adonay) is actually written in the text itself, either before or after YHVH (so as not to repeat the word adonay where it isn't written this way in the text, i.e., unlike places where YHVH is repeated twice in the text itself, when it is meant to be pronounced "adonay adonay"). They ordained that in this case YHVH is to be pronounced aloud as Elohim, which is indicated by the vowels. If their intention was otherwise, then they would not have had any reason for changing the pointing.Many have researched how the name is supposed to be pronounced as it is written, namely what are its actual vowels? Following what I have written , the consonants as they are written in most places (sheva-cholem-kometz) is actually the authentic vocalization. The reason is because the kometz of /yah/ (which we find at the end of theoporic names) at the start of a word is changed to sheva, such as in Yehonatan and the like. It seems to me that this was the intention of the pointers of the text by pointing the yud with a sheva. For if this was not what they had intended, but simply to point according to the name of Lordship (i.e., the vowels of adonay) then why wouldn't they have voweled the yud with a chataph patach in the same manner that they applied a chataph segol when it was meant to be pronounced /elohim/? Therefore I say that it is true that they wanted to show that it should be read /adonay/ but this pointing managed at the same time to preserve its actual pronunciation, which was known to them through tradition.

In other words he is saying that the true, original pronunciation really is Jehovah. We might also add that there is other old evidence for the substitution adonay, as we find in the Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 10 "ר' יעקב בר אחא אמר נכתב ביו"ד ה"א ונקרא באל"ף דל"ת."

As it happens the primary problem with his admittedly strange idea that "Yehovah," as it is pointed, was really its pronunciation (while also alluding to adonay) is the fact that in the oldest Masoretic manuscripts known to us the Tetragrammaton isn't pointed as if it would read Yehovah. It is pointed as if it would be read Yehva. For example, here is a typical example in the Aleppo Codex:

He couldn't have known this, for even though he saw many old manuscripts he probably never saw a Tiberian manuscript as old as the Aleppo Codex. What he did see must have had the later pointing, with sheva-cholem-kometz and he reasonably assumed that this is how it was always pointed. Scholars conjecture that the explanation for thepointing in these early manuscripts is that they were not meant to indicate to pronounce adonay at all, but שמא (shema), which is the Aramaic equivalent of shem (as in Hashem, "the name," in Hebrew). The vowels here certainly work for shema. It should also be noted that the Samaritans say Shema for YHVH and there is early medieval evidence that they did so a long time ago.

Shadal's early evidence from the Septuagint, Hexapla, etc. can't be ignored though, so we should bear in mind that adonay is clearly the ancient substitution and not shema. What is being posited then is really a change from adonay to shema and then back again! If this can be explained, that would be nice.

Interestingly, another sort of witness was available in a limited fashion to Shadal, but as we shall see it would not have been helpful. I am speaking namely of non-Tiberian texts with superlinear pointing. To give an illustration of how obscure many things were which we are privileged in our time to see with ease, in an 1839 article Shadal quoted the Machzor Vitri, which itself had never been printed and only existed in three known manuscripts. He was one of the privileged few who had access to one of those manuscripts, so he was able to quote from it and he printed the following excerpt (Kerem Chemed 4 pg. 203):

אין ניקוד נוברני דומה לניקוד שלנו ולא שניהם לניקוד ארץ ישראלThe Novernian [sic] pointing is not like ours, and both of them are not like the pointing of Eretz Yisrael."

Shadal has two footnotes here. The first emends נוברני ("Novernian," which is meaningless) to טברני ("Tiberian"). Thus the comment, which is speaking of nikkud, states that "The Tiberian pointing is not like [the Babylonian] and both of them are not like the pointing of Eretz Yisrael." Shadal's second footnote makes the observation that these reported facts are a חדוש גדול, הצריך עיון וחפוש הרבה, or a "very surprising assertion which calls for research and much searching" to explain its meaning of. Today you can find examples of the various kinds of pointings in seconds, yet in 1839 even a man with relatively elite access to rare materials had no idea what a statement like that could have meant. He would not have to wait very long to have the beginnings of an idea, for at precisely that time Karaite scholar Abraham Firkowicz was traveling through Crimea and obtaining old Hebrew manuscripts. Some of them had superlinear pointing.

In 1841 the periodical Zion printed the following exciting notice in its Sivan issue (page 152):

As far as I can see the sample of this text was actually printed in the Elul issue, and not Tammuz as stated here. In any case, here is what they printed:

How intriguing this must have been! In fact I remember the first time I learned that there were other pointing systems besides for the Tiberian one we used (who knew it was "Tiberian?") so I can well imagine what seeing something like this must have been like. The one instance of the Tetragrammaton here is preceded by adonay, so it is pointed to read elohim and therefore useless!

The next early example we find in print is in Efraim Moses Pinner's Prospectus der der Odessaer Gesellschaft, etc. (Odessa 1845) which included a facsimile of a page from Habakkuk from one of Firkowicz's manuscripts with superlinear pointing. Unfortunately the copy of this book online doesn't have the facsimile, however in 1877 Hermann Strack printed another facsimile of the same manuscript in the pages of the 5th volume of the Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archæology, so I will show it for the sake of illustration. Being Hosea and not Habakkuk this isn't what Shadal would have seen, but no doubt he saw the page in Pinner's book:

Here's a detail:

The point is that there is no nikkud at all. (The note at the top is a trope sign.)

Since Pinner's other claim to fame is his Talmud translation, of which only one volume appeared, it is worthwhile here to post a picture of his portrait. I think it will be of great interest to people, most having not seen what he looked like before:

See here, here, here, here and here for more about Pinner and the Chasam Sofer, which is the angle of interest with which most people approach that episode.

Between the publication of the small sample in Zion (1841) and Pinner's book (1845) we see from a letter from Shadal to Gabriel Isaac Polak (dated 30 Tishri 5504/ 1843) that he came to possess a hand drawn copy of one the pages from this manuscript. The book was printed in Amsterdam 1846 and includes a facsimile making this probably the third time a page of superlinear pointing appeared in print. Shadal writes in his letter that this particular text was hand-copied by Shadal's cousin and mentor Shmuel Chaim Lolli. He writes that his friend Isaac Samuel Reggio managed to acquire an actual page of this manuscript after the small sample appeared in Zion. His cousin then hand copied (probably traced) it. Shadal attests that it is copied perfectly. In between pages 26 and 27 of Halichos Kedem is the facsimile of this piece of the Bible manuscript found in Crimea. Here is the picture, which we can see is from Isaiah and includes the Targum interpolated in the pages. The Tetragrammaton appears twice. The first time with no pointing and the second with the points for elohim. Once again, interesting, but sheds no light on how to point the divine name:

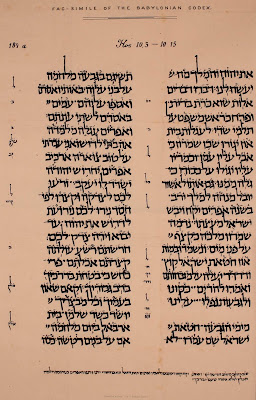

The next relevent text is Simcha Pinsker's Mavo el ha-nikud ha-Ashuri o ha-Bavli (1863) which includes a facsimile of a couple of texts and some transcriptions using the pointing. Pinsker is the scholar who had studied the complete manuscript, as well as some others, in depth for years. Therefore he published his findings, including the keys to the nikkud and trope. As we see in the small samples, the overwhelming majority of times YHVH is not pointed at all. However, I noticed that a handful of cases of his transcription there *is* a single nikkud in the word, and that is the equivalent of a patach over the letter vav. So we'd be talking about something like YHVaH. Probably this is nothing, but I do not know if anyone pointed this out before - make of that what you will. Here's what it looks like:

The point is that whatever limited exposure Shadal had to this pointing in his time would not have proven illuminating. But with the evidence available to him and some careful reasoning he came upon an almost plausible solution. I also think his choice to place this comment on the verse he did - Gen. 2:4 - was very felicitous.